Among Us: Guy Cecil, GDL student and Magistrate

The ‘Amongst Us column’ is new to Lawbore this academic year and when the Lawbore journos team got talking about peers they would like to interview, the first person that popped into Chiara Shea’s mind was her coursemate, Guy Cecil. Guy began the GDL this academic year after serving as a magistrate since 2011. He continues in this role alongside the course at City. Over to you with the questions Chiara…

CS: Magistrates are lay people who volunteer to hear lower-level court cases in their community. They are usually local citizens, without formal legal training, who deliver sentences based on structured guidelines. Can I ask you what made you decide that was something you wanted to be a part of?

GC: I thought it would just be very interesting, to have that window on the world and understand what sort of cases the criminal justice system deals with. It’s one of a number of voluntary things that I have done which has helped me gain an insight I don’t think I’d have gotten otherwise in my day-to-day life. Also, it’s a good way to give back to the community.

CS: Would you say your interest in studying law primarily rose out of being a magistrate?

GC: No, I had an interest in the law before that. It is something I vaguely thought about when I was much younger but, in the end, I drifted towards sciences; kind of the opposite end of the spectrum.

CS: I think that’s the case with a lot of people on the GDL. It’s really interesting talking to everyone, because we’ve all come from such different walks of life.

GC: Yes, exactly. Once you’ve done your first degree, you enter the professional world. You keep your head down, you don’t really have an opportunity to diversify.

A few years ago, I was thinking of doing a criminology qualification, because there are two aspects of law, the practical part and the more theoretical part, and I wasn’t decided on which side interested me the most. So, becoming a magistrate effectively let me dip my toe in the water.

CS: I’ve got to admit, I didn’t actually know much about how the magistrate system worked before I met you, but looking at the association website, it seems pretty intensive. I wasn’t aware just how much of the court system depends on magistrates.

GC: Oh, it’s extraordinary. When people think of the criminal justice system, they’ll generally think of the Crown Court and juries and judges in wigs. In real life, though, the vast majority of crimes don’t get past the Magistrate Courts, because the vast majority of crimes are petty crimes. We deal with pretty much everything that enters the criminal court system. Our stock in trade is summary cases and either-way offences: assaults, thefts, criminal damage, things which are just part and parcel of everyday life, but even grave offences such as murder come into our court initially before being sent up the ladder.

Most of the time we’re not talking about serious crimes, though. With summary crimes, a lot of the mens rea that we are dealing with is impulsiveness or recklessness. There’s often not a lot of intent. We deal with thefts, for example, and you would think that there has to be intent involved, but even then it’s usually opportunistic. There’s a lot of reasons people perform these crimes, obviously, but it’s often just lashing out, or addiction issues, or things which are just part of human nature. I think it’s more of a reflection of day-to-day life than what goes on in the higher courts.

CS: So you’re not facing hardened criminals, so to speak. You have to consider the wider context?

GC: Yes, that is part of what we do. There’s the whole question of why people commit crimes? Are they thinking that it doesn’t matter, or that they might get away with it? Or are they thinking, well, I know it is wrong, but I have to do this because otherwise, I won’t have anything to live off. The truth is, you see people in court, and more often than not they are pretty sorry figures. I’m sure you know that the majority of people will come to court and plead guilty. There are very few trials. So, they’ll come to court, plead guilty, and then you learn about their circumstances. Very often, they have all sorts of issues. What’s very prevalent these days are issues around mental health. So there’s a real challenge in how you apply that in terms of their culpability. There are many purposes of sentencing, but you are always thinking about how you can rehabilitate people and push them in the right direction.

CS: Do you have a certain amount of discretion when it comes to sentencing?

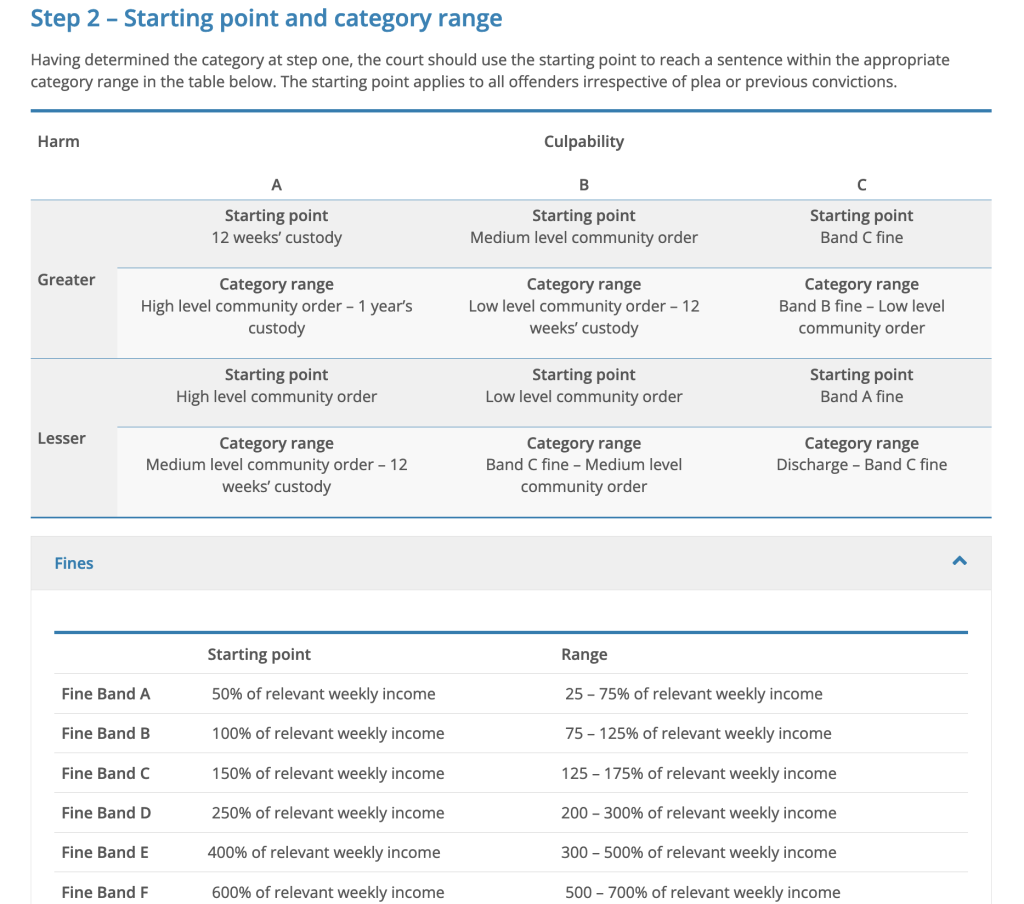

GC: We have a lot of discretion, yes. We have sentencing guidelines, which are published by the Sentencing Council. They’re very useful to determine a sort of baseline for the offence that we’re dealing with, and factor in things like culpability and harm and any aggravation, for instance. The general rule is if you want to sentence outside the guidelines, you have to explain in open court why that is, and offender circumstances are often the key issue there.

CS: Is it fairly easy to stick within the guidelines? Are they flexible enough?

GC: They’re flexible enough because there’s a very wide range for each category. It’s only in exceptional circumstances that you will go outside them, but you are allowed to. We always have to give reasons for any decision that we make.

CS: As I understand it, if your judgment is appealed, you are allowed to go and listen to that appeal hearing. Is that something you ever did?

GC: No, it is actually what I’ve always said is a deficiency in the criminal justice system, that there is no mechanism for feedback. So it’s very difficult to know whether any of your cases have been appealed, or have undergone judicial review. You’re not notified. Well, I have never been notified. Maybe none of mine have gone to appeal, but I don’t think there’s a mechanism in place to let you know if that happens.

CS: How much time do you find yourself dedicating to the role currently?

GC: On average, I’d say I do two days a month.

CS: That’s almost twice what they say the minimum time commitment is on the Magistrate Administration website.

GC: Yes. You can’t just do the minimum because, a) there’s a lot of pressure, to sit more often and b) if you try to do that, you basically forget how to do it. Even now, I’ve been a magistrate for years, but if I don’t sit for some reason for a month, then I do feel that I’m slightly rusty the next time.

CS: I know that they do give you a certain course of training before you start serving as a magistrate, though, as I understand, it’s fairly brief.

GC: It’s very brief – just three days. As a magistrate, you don’t need any legal qualifications, and you only need to have a very basic understanding of the law. That’s because, when we sit as a bench, we also have a legal advisor sitting in front of us who is obviously fully legally qualified and very experienced in court matters, So, you get those three days, and what they’re teaching you is how to make judicial decisions – how to apply the law to the facts. It’s kind of like a more hands-on approach to a lot of what we are learning to do now on the GDL, actually.

CS: That’s a big part of why you’re doing the GDL, if I remember correctly. When we first met, you said that you were hoping to go into the criminal barrister branch, and then work your way up to one day being the district judge equivalent of what you’re currently doing, essentially.

GC: Yes. That’s my long-term intention. District judges hear exactly the same cases as magistrates. The difference is that we sit as a bench of three with our legal advisor, whilst a district judge is legally qualified and has had some experience as either a barrister or a solicitor, so they can effectively sit on their own. I really enjoy being a magistrate, and a few years ago I became what’s called a Presiding Justice. I’m the one in the middle who talks to the court and runs the hearing. I thought, well, this is something I know about, how can I progress with it? If I get a legal qualification, then obviously the experience which must ensue after that, then I could potentially become a district judge and get paid to do this kind of work as a full-time job.

CS: A couple of months into a law conversion course, are you finding that your previous experience as a magistrate is making you think differently about what we’re learning? Or, alternatively, do you find yourself looking at things from a different perspective when you’re on the bench these days?

GC: To some extent, but possibly not to what you’d expect, because the theory of law and the practicalities of what happens in court are very separate.

CS: That’s something that gets brought up a lot during tutorials – that sometimes we need to look at how the law actually works in practice and not just how it’s done in a textbook.

GC. I’m not claiming that we are setting a legal precedent, but it is still important. We apply the law, and I would say that is just as, if not more vital than the one big court decision which makes the news. In the day-to-day business of the court, there aren’t many legal arguments. The law is very clear, the facts are very clear, and we sentence in accordance with that. That means that you don’t actually get into tricky points of law because it’s pretty straightforward. Did A punch B? Well, if they did, then yes, that’s a common assault. It doesn’t require you to have a detailed understanding of the law, per se, because what you are doing is trying to ascertain the facts and then apply the framework.

CS: And that’s what you need most of the time because most cases need to be decided simply and quickly.

GC: Well, the principle is called Speedy Summary Justice. Everything we do should reflect that phrase. It’s that fundamental principle that you can’t just keep delaying until everybody’s happy. You’ve got to go ahead with it. So, if there’s an adjournment application, there has to be a really good reason why there should be an adjournment, because you have to place the impetus on the prosecution to have their case together. The defendant can’t keep coming back to court every few weeks, simply because the prosecution can’t get their act together. You have to weigh up the interests not just of the community you’re representing but of the defendant as well. Many people overlook that. If it was a serious offence, then we’d be more inclined to adjourn it because it’s more in the public good for that prosecution to go ahead. If it’s not very serious, then the ramifications of holding off on the trial may actually outweigh the consequences of the trial collapsing and the defendant walking free. It’s a balancing act.

CS: And being involved in that balancing process made you decide that law was the right area for you.

GC: Yes, very much so. I sit there at my bench and I see justice in action, I see barristers advocating, I see solicitors advocating. And I think, well, actually, I’d like to do that. And I’m not kidding myself that that’s all there is to it, because I know there’s a lot of work behind the scenes.

You won’t get a KC in the magistrate’s court. The barristers that appear there tend to be the junior barristers, learning their trade on the job. Eventually, they’ll go to Crown Court and they’ll do more serious cases, but starting out they could literally get a brief the day of the trial. They have so many cases that they just don’t have the time, so you can tell sometimes that there’s been a lack of preparation.

It can be frustrating sitting on the bench because we have an adversarial system. There’s a limit to what questions we can ask. We can’t initiate new lines of inquiry. We can ask for clarification, but that’s it. So you’re often sitting there just waiting for a barrister to bring up a specific question, just willing them to ask it, only for it to never even get mentioned. That makes our job a lot harder. When you’re trying to achieve a decision, you want as many facts as you can get, but there could be a gaping hole right through the middle of what you’ve been presented with, and you have to try and work around that. Maybe that’s just a criticism of the system rather than any particular barrister’s advocacy skills.

CS: That’s one thing I wanted to talk to you about. A lot of the time, magistrates can come in for quite a lot of criticism from the public, and it’s frequently suggested that they can be overly harsh in their judgments because they tend to become jaded. Is that something you think is a fair accusation?

GC: No, I would say that that’s not the case based on my own experience. Obviously, this is very subjective, but my direct experience is that magistrates do tend to be quite sympathetic towards defendants. I think there’s a very outdated view of that. I’m sure there was a time when the bench was comprised of very angry middle-aged men and I’m sure there were some overly harsh opinions then, but it’s not like that anymore. It is still not representative of society, and I’m not sure how it ever will be. Due to the time commitment required, it naturally attracts people who are either retired, and therefore of a certain age, or are self-employed, and who therefore have their own set of circumstances. I was self-employed, which was another one of the reasons why I wanted to do it.

CS: Would you say that’s one of the purposes of the magistrate system, that someone would sit there and hear your case and be able to approach it on a human level?

GC: There’s two aspects to trials, really. The first is whether we find someone guilty or not guilty, which tends to be a more objective test because you’re dealing with how the facts apply to the law. It’s really when sentencing comes around that you then get more of a subjective input from the bench. The benefit of sitting as a bench of three is that you’re sitting there with two colleagues who might have a completely different background and potentially that might lead to a completely different understanding of the case. So we discuss it, and we get lots of different opinions and then sort of crystallize that into something that works. Eventually it sort of averages out, which is the intention.

CS: Are you usually sitting with the same people?

GC: No, it is always mixed up, but there are certain people that I sit with over and over. Eventually, you understand what their answers are likely to be, where they are on the scale, so to speak. I know that there are certain magistrates that I have sat with who would probably disagree with me about certain matters, or when it comes to grey areas in sentencing. We’re all reluctant to imprison people, but it is our job, if the offence is serious enough. There are still some magistrates who take a softer approach, but that’s fine. That’s just a difference of opinion. I think you either have to have a certain character, or you have to become hardened. There’s stuff that’s really quite unpleasant to read but, speaking personally, I don’t tend to get emotionally affected by the cases. I know there are some who do, and I’ve seen magistrates crying over details of certain cases. It does become easier, though. Black humour is a way of dealing with it. Britain has a culture of black humour, and that is necessary at a certain point.

A huge thank you to Guy for answering our questions so patiently and for giving us such a close insight into the work of magistrates. Anyone wanting to find out more may find the following links helpful:

Become a magistrate (including who can become one and how to apply) from .gov.uk site

Magistrates – who are they (detailed page with video interviews from magistrates) from Courts and Tribubals judiciary site

Ask a magistrate (range of video interviews with magistrates talking about their role) from Judiciary UK on YouTube

Thanks too to Chiara for putting such excellent questions together!

Chiara Shea is a current GDL student and aspiring barrister at City Law School, hoping to practice in the areas of intellectual property and media law. Before deciding to pursue a legal career, she worked as a writer, researcher and academic in the fields of literature and the arts. She is a graduate of Balliol College, Oxford, and holds a doctorate in modern American poetry and spatial theory from King’s College London. She lives in North London with her two (very spoiled) cocker spaniels, Waffles and Bowser, and will subject anyone to photos of them if they so much as loiter near her for too long.