Ashley Gate, Lawbore journalist and LLM student, gives her views on generative AI from the jumping-off point of a talk from Professor Dan Hunter at the Kings Festival of Artificial Intelligence last month…

I’ll begin this write-up with full disclosure. I am rather concerned about the latest advancements in generative AI technology and the lacklustre regulatory developments which trudge slowly behind. But as the old proverb says keep your friends close, and your enemies closer so I sought to educate myself further on the anxiety-inducing matter. As it happens, late May marks a celebratory time for the King’s Institute for Artificial Intelligence as it holds a week-long festival, and complementary month-long showcase celebrating the technology. One of the many speakers being hosted by the festival was Professor Dan Hunter, Executive Dean of the Dickson Poon School of Law at King’s College London. Hunter has been researching AI law for more than thirty years, ‘long before it was sexy.’ A charismatic and personable orator, Hunter made it clear that he is the founder of multiple generative AI startups. So while his take on the ethical concerns mounting against generative AI was humourous and charming, it was also incredibly biased. In the end however, even he repeatedly expressed deep concern and fear, making it clear that ‘we’re in a lot of trouble.’

Let’s back up for a moment to find out exactly what generative AI is. According to King’s College, Artificial Intelligence is the ability of machines to exhibit behaviour that would be deemed intelligent if exhibited by a human. The term was first coined in 1956 as an umbrella statement for many forms of computer-based processing, computation and development.

Throughout the 1980s and onward this sub-field ran into a ‘dead end’ of sorts, as the directional mathematical models being fed to the computers failed to create a ‘creative’ breakthrough. That is until the 2010s when scientists, like Jeff Hinton who recently resigned from Google over his concerns about the tech, began ‘training’ model algorithms with massive subsets of pixel-based data.

These models are built on non-linear algorithms, meaning that their output will be non-linear. In other words, language and image models can be trained and thus deployed to create ‘new stuff.’ Large-Language models, like Chat GPT-4, act like ‘autocorrect on steroids,’ and create original realistic work by combining concepts, attributes and styles. These scientists invented creative intelligence, similar to that of a human. In many cases the newest generative AI is better than human, scoring in the 99th percentile when it took the SAT, GRE and multiple law/medical school entrance exams.

Now that the artificial can ‘create,’ how is it any different from us humans? Hunter assures the audience that AI is neither sentient nor conscious and doubts that will ever be the case. While the ability to produce language is commonly viewed as a proxy for the ability to think, this isn’t so.

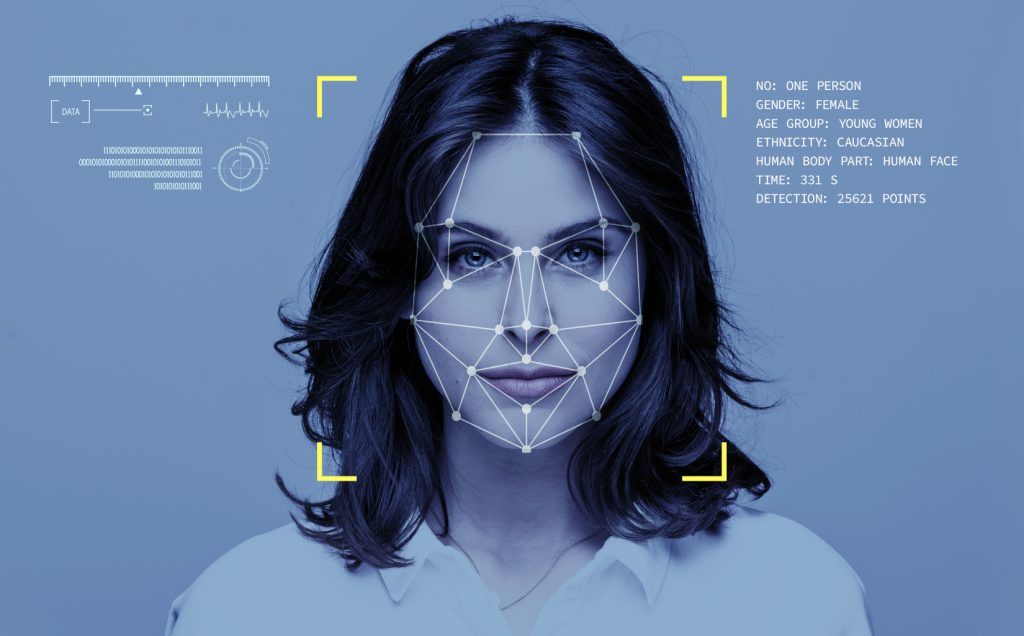

Generative AI only has an understanding of language in the mathematical sense. What looks like thinking is just the model stringing language together based on previous algorithmic training. So while we may be safe from the ‘Terminator’ scenario for the time being, Hunter warns that what we should really be worried about is the human-created uses of this intelligence. It is the humans behind the technology, not the machines themselves, which are cause for concern as facial recognition software is used to strengthen mass surveillance capabilities and lethal autonomous weapons threaten the foundation of humanitarian law.

Obviously, the news on the AI front is not all bad, incredible technological advancements have occurred through the use of artificial intelligence, such as a new antibiotic which can kill a very deadly ‘superbug.’ It is not the technology I am fearful of. If properly policed and regulated, artificial intelligence can continue to be a very capable tool in humankind’s box of tricks.

The slow-moving bureaucratic ways of policy have left even the newest EU regulations obsolete. Yet obsolete policy is better than no policy at all. Some countries — such as my homeland, the USA — lack even bare-bone legislation to protect consumers and reign in artificial. Instead, Hunter contends that it is up to ‘good players’ to implement safeguards such as watermarks which can differentiate AI-created material. Yet these same players, including Google, Meta and Amazon, have begun urging for national and international regulation. This is an unusual move for the tech sector, leading some to worry that these players, which Hunter has tasked with regulating AI, may lack the ability to control their creation. Our speaker also warned us that anything placed into an AI generator automatically becomes public data which the model uses for subsequent training. Accordingly, I urge everyone to be wary of typing in any personal or sensitive information into these chatbots.

As we will see, however, global policy is jagged and lacks the uniformity needed to tame such a wild beast. This leads us to the abundant ethical dilemmas created by generative AI. Since it lacks morality which is commonly attributed to consciousness, AI is also known to lie, and it does so rather often. Why? Because it has no reason not to, it was created to generate, not be honest. Thus, the tech can be guided to produce anything, including misinformation, libel and deep fakes which have horrifying social, political and legal consequences. AI has already been used to create fake articles accusing professors of sexual assault, and that is just the tip of the proverbial iceberg of falsehoods which these generators can draft.

While the creators of these language models did set up some guardrails, (Chat-GPT 4 will refuse to teach you how to build a bomb, for example) one cannot guard against the infinite. In the legal realm, copyright infringements and trademark lawsuits have begun to sprout up against the models’ creators. Additionally, the commercialisation of AI has led to a mass overtaking of jobs and activities which were once inherently ‘human’ such as music generation, art creation, and writing such as investigative journalism (which hits very close to home). Back in March, for example, DJ David Guetta used speech AI to generate a feature of the rapper Enimem that was completely made up. A faux collaboration between Drake and The Weekend was also artificially generated and quickly removed from Spotify. Anything you may envision, for better or for worse, AI can be integrated. The future of our current legal and creative order rests on shaky ground. Hunter is certain that ‘we will get through this, but there will be a lot of disruptions on the way.’

Acting as an AI public relations manager, Hunter compared the development of generative AI to the invention of photography, a life-altering yet beneficial discovery. However, I fear a better-suited analogy would be that of the Manhattan Project which developed the first nuclear bomb. No matter the metaphor, Hunter makes it clear that there is no way to pause this technology, we must instead ‘stop consulting and do something.’ We must begin wrangling the beast. In related news, Chat GPT-5 is set to be released this December.

If anyone is interested, the King’s Institute for Artificial Intelligence Exhibit: ‘Bringing the Human to the Artificial’ will be open for public viewing until June 30th and is located at:

King’s College London, Bush House, 30 Aldwych, London WC2B 4BG (use the back entrance by St. Mary Le Strand Church)

Ashley Gate is a master’s in law student specialising in international Human Rights Law. With a previous background working as a medical aid during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic back in United States, she has a keen eye for the intersectional aspects of health inequity.

Ashley has a passion for politics, history, and gardening. Ashley is a member of the 2022-23 Lawbore Journalist Team.