After completing my very first podcast in the company of the legendary Charon QC (the only man I know with a voice as wonderfully deep as Tindersticks frontman, Stuart Staples), I got thinking about a post on legal education, legal research and law librarians.

flickr.com

Actually teaching students how to carry out their legal research is on the wane; the new BPTC no longer includes a formal legal research skills assessment, with such skills now being assumed to be covered within other subjects. Within most undergraduate programmes the law librarian will have some kind of presence, whether it be embedded within the curriculum and face-to-face, online via tutorials on a VLE, or wheeled out to give an en-masse demo to hundreds of students on the finer points of the legal databases like Lexis and Westlaw. At City, Legal Method is where students learn how to do legal research, alongside the other core skills of legal writing, mooting, ELS, sources as well as reading cases and statutes. This is a compulsory module and is taught by an academic and myself. The research elements are taught via a mixture of lecture and hands-on workshops and importantly, are assessed.

Students at law school have the hardest transition I think; there are so many things to learn even before you can start to make sense of the substantive law – legal citations, hierarchy of sources, precedent, statutory interpretation, as well as all the terminology.

Often students will find the level of reading difficult, the required quantity hard-going. Reading a journal article within a big academic journal like the LQR or MLR can seem impenetrable at first. It’s a big leap to make from A-levels. This isn’t helped by the fact that the more ‘connected’ students seem to be, the harder it seems to be able to focus hard on a deeper reading as opposed to a quick scan of the abstract. The question everyone asks is ‘do i really have to read the whole case?’. At first, students search the databases as they would Google, often only looking at the first page of results, which can result in missed opportunities. When they get the hang of the more sophisticated search possibilities within these tools (e.g. proximity searching) it can change their academic life. There has been much lively debate about how our habits have changed as we’ve become so dependent on the Internet; can we focus at the level required within academia with so many competing technologies grasping for our attention?

flickr.com

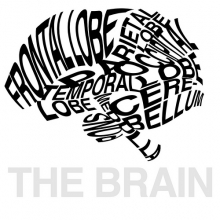

Many have suggested with gains in our multi-tasking ability come losses in our concentration and capacity to deep-think. Nicholas Carr sparked much debate from neurologists when his book, The Shallows: What the Internet is doing to our Brains, was published at the end of 2010. Carr’s article within Wired magazine begins “The Internet is an interruption system. It seizes our attention only to scramble it” (May 2010). He goes on to talk of how we revel in distraction, can’t bear to to feel we’re missing out on anything (email, texts etc) and that skimming, rather than deep thinking is our ‘dominant mode of thought’.

A report commissioned by the British Library into the ‘Google Generation’ (Jan 2008) highlighted how students no longer ‘read’ but jump around, skimming many different sources on the surface. Listening to one of the report’s authors, David Nicholas last week at the LILAC Conference he likened this ‘bouncing’ from one source to another to his teenage daughter flicking incessantly through TV channels.

My observations match this, and hey I have many of these characteristics myself. I’m not so convinced it’s a wholly new phenomenon; surely we’ve always skimmed even in print media? Law students have always worked on desks surrounded by textbooks, statutes, law journals and reports. That said, the distraction thing is certainly valid; getting down to some in-depth reading and research requires some serious dedication. And what of those courses where students are provided with materials in a handy coursebook, rather than being expected to find things themselves? Where does this leave them when they have to stand on their own two feet?

I am just old enough to remember the old command-line interface of original Lexis and I often tell students about how research used to be (I’m a bit young for the “in my day….” spiel but I can’t resist it sometimes) because I think it’s important to value what superb facilities are available to us now. Anyone who has laboured through multiple volumes of Current Law Case Citator to trace the history of a case will tell you that! Most law schools will spend far more on their database provision than buying textbooks.

But whether being able to access things online so quickly makes the students of today better researchers than those of 12 years ago, who used to rely on hard copy stuff on the library shelves and the odd CD-ROM, I’m not so sure. The undergrads of the 2011 come into Higher Education with a swaggering confidence online: they are used to living their lives online via Facebook and YouTube and their strategy if they need to find something out is generally to google it or ask a friend (although I reckon asking a librarian does come pretty high too). There’s absolutely nothing wrong with this, I use google for loads of things, but academic legal research is not one of them. We wouldn’t pay the vast sums of money to Lexis or Thomson Reuters otherwise! We pay for ease of use, value-added information and breadth of sources. The academic journals which an LLB or GDL depend on are not available for free.

There are some excellent free sources online, and this is increasing. The UK has been madly under-provided for in terms of legal information for the citizen compared to other jurisdictions, but this is on the change. For case law the immense BAILII offers full text of cases from the jurisdictions of the UK but also offers the most recommended cases in each subject area via their Open Law project (fabulous for law students at degree level). The access to amended legislation for free only happened last year at legislation.gov.uk despite being in use within government for years.

[Donate to BAILII – they’ll be very grateful!}

What is also excellent is that the tide is changing in terms of commentary; lawyers are giving their views more readily than ever, particularly in the form of blogs. This means we can get access to rapid opinion on the breaking judgments, which whilst not holding the weight of an academic peer-reviewed journal, comes out a good deal quicker and enables the student to engage with law of the moment. A tool such as Twitter means that you can get hot-off-the-press news, commentary, links and opinion all the time. For an excellent round-up of the most influential blogs, see Brian Inkster’s UK Blawg Roundup: Time Travel Edition (8 April 2011) from his Time Blawg site.

flickr.com

As librarians, our role is, as ever, to act as guides through the countless types of legal source. This could be to help a student find resources for a tutorial, for an assessment or for an upcoming moot. Put simply we know how to find stuff. The challenges for student researchers have increased as access to legal information has; knowing what information to trust, which authors are respected, how to analyse and evaluate sources, knowing the shortcuts that work are all pivotal.

The exciting thing for librarians is that boundaries have blurred, we are no longer defined by our space, but ‘out there’ getting involved in our subject in ways unthought of a few years ago. We are able to use our expertise to give advice in new ways (I get asked lots of questions via Twitter for example), to create resources for students which can change dynamically to their needs at that point in time. It sounds cheesy but I really feel that through a combination of my formal teaching, ad hoc advice in my office, online tutorials on Learnmore and the many different elements of Lawbore, I’ve engaged students in a far more beneficial way than previously. All of the resources I create depend totally on my everyday contact with students (both face-to-face and virtual); getting an insight into where difficulties exist and shaping new resources to help ease these. For example the Remembering Cases piece grew out of a student question, and I got some great help from lawyers and students on Twitter too! Get to Grips with Law Reports was prompted by a series of recurrent questions around this legal source.

Some closing thoughts…students do make use of your law librarian – their job is to know where to find all kinds of obscure information. They can usually give advice on a whole range; the law, study skills, using the legal databases, referencing and plagiarism too. This can depend on institution; at City I work hard to create resources which stretch these boundaries further; by creating networks with our alumni and careers centre to make sure we can get useful legal careers articles and interviews available via the Lawbore blog, as well as the enormous resource that is Learnmore Mooting.

Investing time in developing your expertise in legal research will pay off; don’t get to the end of law school only using basic searches in the databases and still reliant on your textbooks – this will leave you exposed later on in your career. In a somewhat dated analogy. the library is often described as the laboratory for lawyers – the place where you experiment, try things out, find your voice (create some big bangs even?) Of course ‘the library’ these days equates not only to the physical space but also to all the online resources that are made available to you.

Last year I started an accelerated degree. When questioning the condition of some of the popular cases in the library books I was told I should never need to refer to them and to go on Westlaw instead. There were classes on using westlaw but none on sourcing stuff in thelibrary. I’m lucky, I had previous academic experience but group work highlighted how these kids straight out of school were unable to do anything without referring to google and not even the scholar version. Work of A grade students filled with legislative mistakes and referring to completely different jurisdictions because an online law dictionary suggested it. It scares me but I guess I’m just an old fart stuck in the past.

Thanks for your comment – it’s reassuring to know it’s not just my impression! It is scary; these issues exist both at undergrad level and in a different way on conversion courses. I’m asked some very basic things by students nearing the end of their academic legal studies. Interesting that you say there was help on legal databases but not on what was in the library – the focus is often on what’s available electronically rather than hard copy, and I sometimes feel that if a student has no experience of even using an index within a book, some of the fundamental stuff about organisation of information within a database doesn’t make sense…