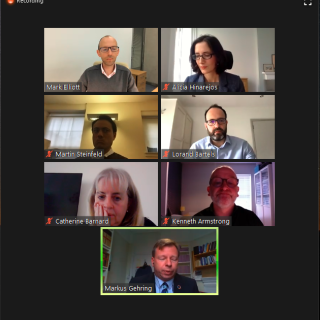

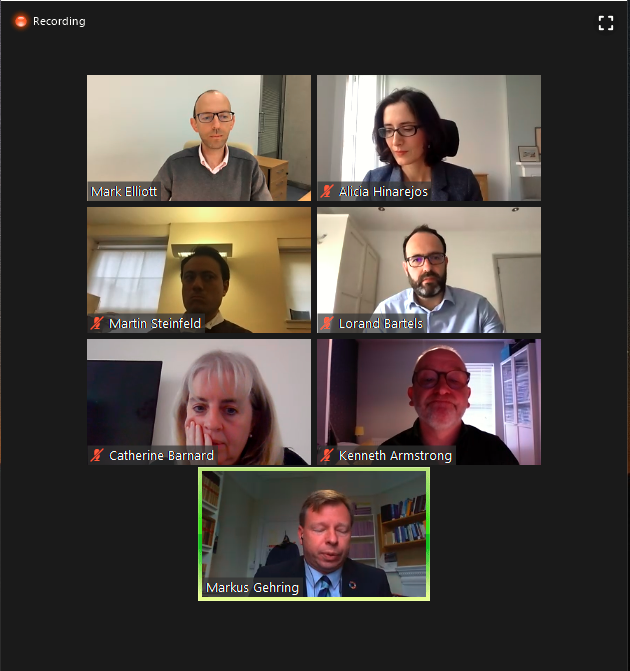

A silver lining of the Coronavirus pandemic has been the array of different online events that one has available to watch. When I saw an advertised event on Twitter on the Internal Market Bill being run by three research centres within Cambridge Faculty of Law (The Centre for European Legal Studies (CELS), Centre for Public Law (CPL) and the Lauterpacht Centre for International Law (LCIL)), I was immediately excited to watch. This was a topic I had already come across a bit, having already written an article about it, and so it appeared like a great opportunity to hear the views of some of the nation’s foremost academics talk on the subject.

The webinar itself was split into three sections each dealing with different aspects of the Bill. This began with a discussion of the Northern Ireland Protocol. Professor Catherine Barnard started this section with an analysis of the substantive content of the Bill which served as a useful reminder of the issues at hand. The relevant sections of the Bill she mentioned were Clauses 42, 43 and 45 which all gave Ministers’ powers to disapply certain sections of the Withdrawal Agreement in varying ways. This has been strongly criticised by academics and politicians alike, since it seems to provide consent for Ministers to act unlawfully.

The view Barnard took on the subject is that the creation of such powers were largely unnecessary given they fail to deal with the problem Michael Gove, the Minister for the Cabinet Office, raises of the EU imposing checks for goods moving across the Irish Sea. This is because this bill will only regulate exports from Northern Ireland to Great Britain rather than the concern that the EU will do the opposite.

A point of debate that was rather enjoyable to watch was on the nature of Article 16 of the Northern Irish Protocol which Professor Barnard believes to provide many of the safeguards that the Government wish to create in the Bill. However, Dr Bartels does not seem to agree with this view; he explains that traditionally safeguards are made to prevent a shock to an economy whereby additional imports from an FTA could damage one’s domestic industry. Although Article 16 is slightly broader than the average safeguard and applies to exports rather than imports, Dartels submits that it is not broad enough to carry the kind of safeguards that the Government wish to create in the Internal Markets Bill.

I particularly enjoyed the explanation Professor Alison Young gave about the changes to the Ministerial Code and the ramifications this has for the Rule of Law in this Bill. In 2015, the code was updated so that it was no longer specified that international law obligations were binding to Ministers.

However, when this was challenged it was ruled that international law remained a part of ordinary law, therefore Ministers remained duty bound to comply with the law under the Ministerial Code. This means when Suella Braverman, the Attorney General, aims to differentiate between international and domestic law, under the Ministerial Code such a differentiation is irrelevant. This appears particularly problematic for Robert Buckland, the Lord Chancellor, given that his oath requires that he will uphold the rule of law. Given this bill does break the law, then his position appears untenable.

The talk ended with a brief Q&A. A problem with the bill I had was with Section 45 which seemed to create ouster clauses whereby Ministers were permitted to break any domestic or international law obligation in certain ways. Given as recently as last year in R (Privacy International) v Investigatory Powers Tribunal such powers were fiercely criticised by the Supreme Court I was interested to see whether there was a way the Courts could reconcile Parliamentary Sovereignty with the view that they should provide a supervisory function over executive conduct. See the UKSC blog for a case comment on the IPT case.

Professor Young responds to this first by saying that Lord Woolf’s obiter statement that the Courts could act without precedent where the Rule of Law was clearly threatened may be applied. Professor Mark Elliot argued differently, and it is submitted more convincingly, that the explanatory memorandum issued on the Bill argued that this wouldn’t impact judicial review done on normal grounds. Therefore, it follows that when interpreting the statute this could be applied to find a way around the ouster clause. What must be noted is that this is purely exploring hypothetical ways that a Court could respond if the powers detailed in Section 45 were used. In actuality, they all agreed that it would take a very bold Court to issue such a judgment, and one would hope that such a question never had to be considered.

Overall, this was a very entertaining event, and would be particularly useful to those who have completed a Constitutional Law module. At times the issues that were being dealt with were abstract and complicated, but this made for a thoroughly interesting intellectual challenge to understand and contemplate the debates that they were having at the highest levels of academia. I’d certainly recommend that anyone interested in public law stay tuned to watch the upcoming webinar events within the Faculty of Law at the University of Cambridge.

Many thanks to Tom Spencer for this detailed review of an event not for the faint-hearted!

Tom is an LLB2 student and a member of the Lawbore journalist team. He is interested in pursuing a career as a barrister and regularly writes for a number of platforms writing on a range of issues from constitutional affairs, bar applications and economics.