We had a report from Richard Griffiths on the first day of this packed conference, but the second day was covered by fellow Lawbore journalist, Clemency Fisher.

The second day of the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies’ Regulating AI Conference was exceptionally topical, and involved eight speakers presenting the challenges and opportunities which accompany legislating Artificial Intelligence. Presentations focused on international approaches to AI, and despite problems arising from this new digital form, the tone of the conference was overwhelmingly positive, focusing on the many opportunities AI poses, and emphasising that mistakes encourage innovative to AI governance. Specifically, the concept that legislation may be integrated within AI systems was repeatedly mentioned, indicating a novel non- human interaction with the law.

Panel 4: International approaches: AI governance and scrutiny, chaired by Dr Lachlan D. Urquhart

Professor Matteo Ortino opened the panel discussion with a presentation considering the final draft of the EU’s 2024 AI Act. He highlighted Article 40(3) of the act, which assumes the high-risk AI platforms to be legal if they have met official EU standards. Professor Ortino queried the purpose of this Article, and its enforceability-standards represent guidelines rather than legislation. He noted that the Article grants the Commission discretion in determining what may be deemed acceptable risk, rather than providing a clear legal outline, possibly to appease regulatory concerns in big tech companies. He noted the upcoming Digital Omnibus as a continuation of the EU’s deregulatory policy regarding AI.

The second presentation, by Dr Michael Sierra, focused on the potential of regulatory sandboxes to test AI. For anyone as technologically unversed as I was, a regulatory sandbox is a controlled environment where companies may test their new products under the supervision of a regulator, without the immediate consequences of the ordinary regulation. In 2016, this was adopted in the UK to test new financial technology, and proved a popular solution, being used by 118 firms with similar initiatives developed in Singapore and Israel. Dr Sierra promoted these sandbox experiments for AI – to better understand it; prepare legal risks; and remove entry barriers. However, he noted that risks included companies exploiting regulatory arbitrage, non-uniform regulation between tests, and the ethical issues which accompany testing new AI models on humans in low-regulated environments.

Dr Anja Pederson followed with a critical analysis of Danish use of Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) in criminal investigations. In June 2024, Denmark introduced FRT into the police force, following two deaths in a Copenhagen shooting.

The change was announced via press release, and justified through Article 10(20) of the Danish Constitution, which allows the police to process personal data when necessary for investigations. This press release was met with criticism, specifically, The Danish Institute for Human Rights queried the unregulated powers granted to police to process sensitive personal data. Dr Pederson considered alternative ways FRT may be legally implemented, suggesting transparent public consultations instead of only an ‘insane’ press release.

The panel closed with Dr Chi Jack-Osmiri’s comments on how intellectual property may evolve in response to the growing autonomy of AI. Specifically, regarding attributing responsibility. Dr Jack Osmari commented that referencing the person who commissions the content would fail to consider unsupervised acts by AI. Her solution was to create a new theoretical approach – to train AI to recognise IP boundaries, in a similar way that AI is trained to “supposedly” avoid bias, (I fully agree with Dr Jack-Osmari AI’s not-completely-removed bias, since I had to re-prompt Chat-GPT three times with ‘AI conference, half of participants are women’ to create a conference image (fig 1) which was not male dominated, and representative of the IALS conference itself). Dr Jack-Osmari ended with an optimistic tone, considering that AI may become a self- regulating means of attributing intellectual properly, if correctly supervised, and trained.

Keynote panel: International Perspectives: Oversight and enforcement of AI, chaired by Dr Nóra Ní Loideain

Opening the final panel, Ben Saul, the UN Special Rapporteur on. counterterrorism and human rights, delivered a note on the possibilities of AI to be used in Counter-terrorism efforts, arguing the new technology held great potential. However, Saul emphasised (along similar lines as Dr Pederson’s Danish Case Study) that there must be safeguards on data quality, considering the new danger of AI military threats if bestowed with this power.

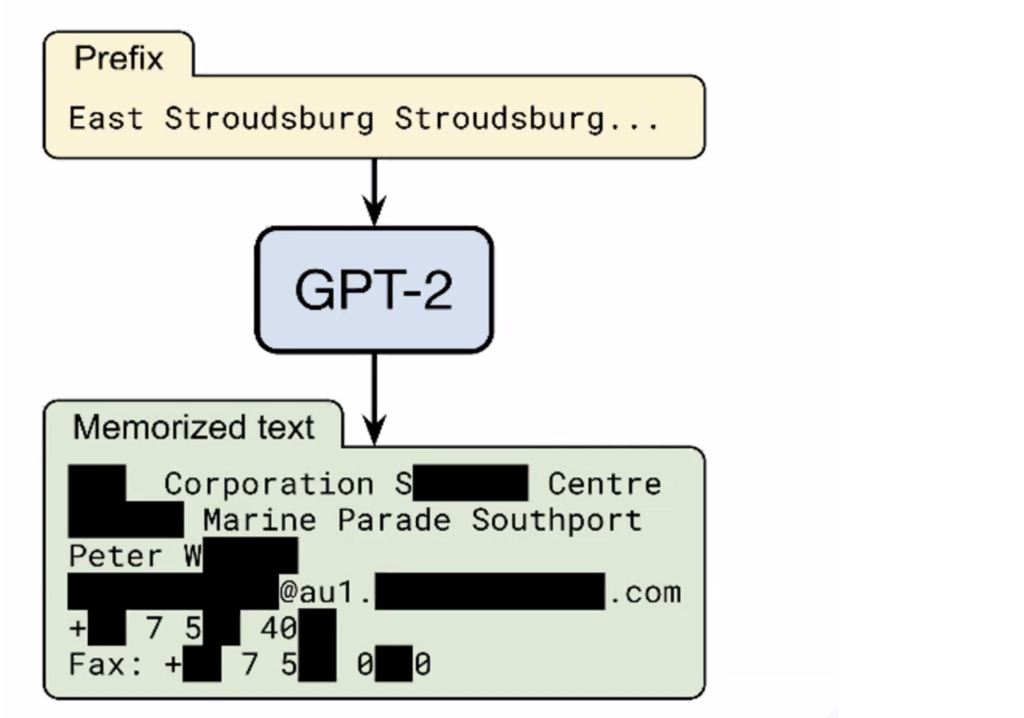

Mukleni Dimba questioned how data laws may keep up with the pace of AI development, illustrated by an example from Chat GPT-2. Chat GPT-2 was programmed to respond to prompts by changing words into statistical probabilities of what the nextwould be, and subsequently outputting memorised text. However, there are no data controls to this memorised text and inputting the prompt ‘East Stroudsburg Stroudsburg’, Chat GPT-2 output memorised personal details (fig. 2). In response to the dilemma of privacy concerns, Italy temporarily halted the use of Chat-GPT, to ensure that the AI appropriately respected data privacy, before being nationally used.

Helen Dixon delivered a presentation on the EU AI act, taking a slightly different approach to Professor Ortino, believing it to be an important development for human safety and fundamental rights. However, Dixon noted that the phased application (not enforceable until August 2026) had challenges.

She also promoted a suggestion put forward by Yuval Noah Harari, that AI should have ongoing observatories to regulate data protection.

A different, and political, perspective was offered by Alexander MacGillivray, the senior Technological Advisor to the Biden administration. MacGillivray noted that the past administration’s attempts to regulate AI, such as the 2024 Executive Order on Safe Secure and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence, built the foundations of a legislative framework, but were removed by the Trump administration. Subsequently, laws at a state-level have aimed to create regulation. However, MacGillivray suggests, in line with more recent new, that an upcoming Executive Order from the Trump administration will be shortly released to address state deviation from federal policy.

Stephen Luciw was the last panel speaker, and similarly commented on the underlying effects of policy guiding Canada to move away from regulation. Luciw mentioned a recent case where an AI bot obtained, and shared, patients’ healthinformation from a doctor’s account. The case highlights the urgent need to regain control on the data that AI has access to.

A great range of material was covered by the conference, and it illuminated the shift that AI impresses on society, and subsequently, the law. It brings data concerns alongside outdated legislation, into the forefront of modern challenges. Yet it has the potential to relieve the law of the heavy-lifting: Will the ‘self-improving’ capacities of AI, allow for Dr Jack-Osmairi’s suggestion of an autonomous self-regulating legal framework to materialise?

Clemency Fisher is a GDL student who studied Archaeology before converting to law. She loves modern art, archaeology, and politics, and is interested in pursuing Criminal or Public Law after the GDL. Outside her studies, she enjoys running, visiting art galleries, and watching The Traitors. Clemency is a member of the 2025-26 Lawbore Journalist Team.