The Lawbore Mental Health and Wellbeing Interviews: Neil Graffin

Any profession will have its own trials and tribulations, and the legal profession is certainly no exception, posing its own set of challenges that can cause strain upon the mental health of all those involved. Given the increasing societal awareness and the importance it plays in our day-to-day functioning, maintaining good wellbeing is key to flourishing not only as a lawyer, but as a human more generally. One way to learn to keep mentally well is by seeking lessons from the experiences of others.

Neil Graffin is a Senior Lecturer in Law at The Open University, and co-authored the book ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing in the Legal Profession’. He is currently collaborating with the charity LawCare on their ‘Fit for Law’ project, which is a free online educational training course designed to help legal practitioners and employers by developing emotional competence and professional resilience. His other research interests lie in human rights, immigration, and asylum law, and he is also an Honorary Secretary for the Socio-Legal Studies Association (SLSA). He speaks to us about his interest and experiences about the development of wellbeing in law.

How did your interest in wellbeing in the legal profession develop?

Although I wasn’t a practitioner myself, some of my friends and a member of my family practised in immigration and asylum law and I became aware of the many challenges of the profession, and particularly the fact that asylum practitioners work with traumatised individuals and hear traumatic narratives on a daily basis. I conducted a study on this, researching the emotional impacts of working in the profession, where practitioners talked of burnout being an issue within the sector.

They also mentioned that many practitioners did not stay in their roles long. As immigration and asylum law are very complex, with experience being important in ensuring good legal representation, I thought that to be very problematic. As a result of this, I started to look at wider issues of lawyer wellbeing. Initially, I was mainly concerned about the effects of issues like burnout on legal representation, but this increased when I discovered the scale of the issue to be so large that it had become an ethical problem.

What has been the biggest change in the approach towards mental health support from when you first came to work in relation to it?

I am relatively new to undertaking research in this area (since 2017), but I am finding that there has been a growth of concern about the mental health of legal professionals within the last few years in the United Kingdom. This is being driven by various stakeholders – whether it is practitioners themselves, the regulating bodies, the various law societies, or charitable organisations such as LawCare. There is also a growing interest in academia; the UK has been playing catch-up, but there is now a growing literature in the field.

What do you think is the biggest challenge to mental health and wellbeing in the legal profession at the current moment?

I am very much of the view that it is cultural and structural issues causing the most damage. While I do think self-care is important – mindfulness, for example, definitely has its benefits – there are systemic issues across the profession that need addressing. These range from issues around stigma of admitting to poor wellbeing, a perceived need by practitioners to appear strong and in command at all times, as well as the cultures of long working hours and high billing requirements.

Some of the issues around wellbeing have risen from a long cultural and structural history in the legal world. How do you think we can begin to undo these long-term changes?

In our book, we argue for a manifesto for change which calls on a multi-faceted approach to improving lawyer wellbeing. This includes responsible regulation, support from representative bodies, and for employers to take stock of the environments that they have created and make changes. We also argue for education on issues of wellbeing, and the continuation of campaigning from those in the sector and outside it. In conducting our research, we heard of firms not following the industry norm of allowing staff to work long working hours and have high billing requirements. This is not an easy choice to make in a competitive environment, but can have benefits for both employees and firms in the long run. Having a well-being policy is important – but not one which solely asks employees to conduct their own self-care, allowing employers to evade their responsibilities in creating a less stressful, and safer, working environment.

Would you be happy and comfortable to share your own experiences of mental health?

I recognise that like many people, I am maybe not as open as I could be when I’m stressed out or anxious – this is something we all need to work on. I know myself when stress has got to be too much, and I find running or walking to be a good antidote particularly during the pandemic. However, it is difficult to admit to mental health issues. I think people do not want to admit that they do not have the power within themselves to overcome difficulties – that it should be easy for them. In reality, when a person’s wellbeing is affected too much, it becomes increasingly difficult for them to get back to feeling well again.

A colleague once said to me that when the tank is completely empty then it is much more difficult to fill up, and I think that analogy definitely works.

What advice would you give to your younger self in regards to mental health?

Try not to do everything at once!

How do you manage high pressure and expectations? Would you say the expectations are external or self-imposed, and if self-imposed, how do you keep a healthy balance?

As an academic, it is a mixture – some are external and many are self-imposed. I’m not sure if I am keeping a healthy balance, but I try. I am very lucky in that I enjoy my work, which means it is less of a drain on me than other jobs I have done in the past, but it is a double-edged sword as enjoying work can also mean you are inclined to work more on occasion. I am not someone who particularly likes looming deadlines, so I do try to give myself plenty of time to do tasks, and sometimes that works, but sometimes it does not.

What is the most stressful part of your job, and how do you deal with it?

I’m not sure if there is one part of my job that is the most stressful, but one thing that I have noticed recently and I have discussed with colleagues is the potential for online meeting fatigue. This seems to be an increasing concern during the pandemic. It is interesting, as at the beginning of lockdown, workers were being advised to connect with other colleagues when working at home – which, of course, is also very important – but online meetings themselves can be very demanding, especially if you have many within a day. We have recently instituted meeting and communication-free days in work, so colleagues can concentrate on other tasks and these have been helpful.

What surprised you the most when you were researching for your book ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing in the Legal Profession’?

What surprised me most was the scale of the demands placed on professionals, in particular relating to the amount of time that they work in a day, and how that affects other parts of their lives. For example, the fact that people could not have proper relationships with others, or meet new people, because they spend so much time in the office.

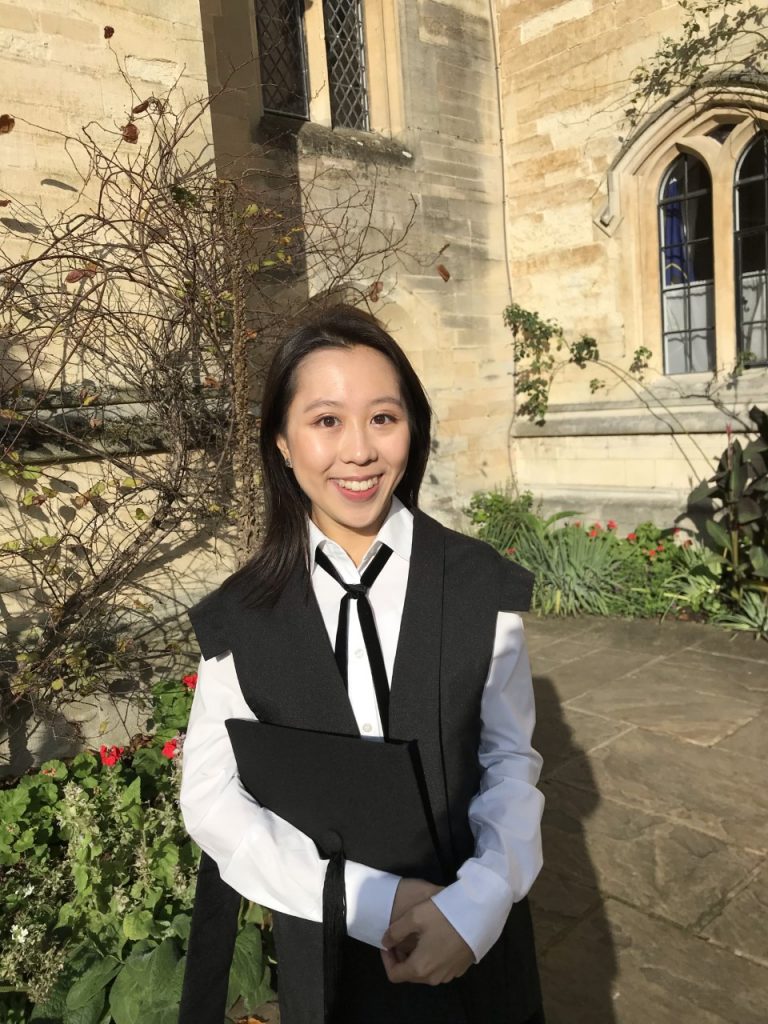

Many thanks to Athena Kam for this interview in the Mental Health and Wellbeing interview series. Athena is a second year law student at the University of Oxford, with a view of becoming a barrister one day.

She is the President of the Oxford University Bar Society, having previously held the positions of Mooting Officer and Secretary. She hopes to help push for a more inclusive and mental-health legal profession.