Academic Corner: Interview with Enrico Bonadio

“It doesn’t matter whether the process of creation is illegal or legal – art is art, and copyright protects art.”

Could you say a little about your professional work and what drew you to law in the first place?

I am a Reader in Intellectual Property law at the City Law School. In the pre-covid world I used to travel a lot to give classes, conferences, workshops, training and technical assistance for international organisations, which I do online now. I love what I do. I joined academia 11 years ago and have spent a decade now at City and I love it.

Why don’t we start by talking about your recent work on copyright law and art. You’ve recently edited a book ‘The Cambridge Handbook of Street Art and graffiti’. What drew you to this area of copyright law?

Well, the environment I have found myself in. When I came to London for the first time 10 years ago, I lived in East London – Bethnal Green, Brick Lane, Shoreditch. It was full and still is full of street art. So I didn’t choose the topic, the area which I was living in chose the topic for me. The environment around me was crucial to get an interest in these artistic movements. Then of course I was already a copyright enthusiast so I decided to marry these two interests. I started observing, talking and befriending many writers and street artists, and that’s how I started my ethnographic research. So, my work now is more socio–legal than legal I would say.

What is the legal definition of street art?

There is no legal definition. Within those laws which fight graffiti as not as art but as vandalism, it is described as scribbling, visual pollution, vandalism etc. But this is not really the right definition. There is no recognised legal definition of street art and graffiti. I don’t accept those anti-graffiti laws which are local laws. Apart from that there is no other definition of graffiti in a stated sense.

So it is more about protecting street art for you. Do you think street art can be protected by copyright?

Yes I do. Even the illegal art because I think that the issue of illegality should not be conclusive when it comes to granting protection. It’s a bit controversial – not all commentators agree. And in several countries this is still a grey area of copyright law.

In your work you argue for methods of conserving street art in ways which make it authentic as possible, and you also explore the paradoxes of this as well. You explore situations where the conservation of street art risks institutionalising the art. Do you think that legalising street art would take away part of its authenticity or its edge?

Probably, yes, it would. And as aficionado of this form of art, I wouldn’t like that, because it would lose its very nature. But copyright could still apply to illegal works, as I said before. It doesn’t matter whether the process of creation is illegal or legal – art is art, and copyright protects art. That’s it. It doesn’t protect just legal art. I’m waiting for a judge to explicitly say this, because so far we lack a case where the judge explicitly says so. So far judges have not faced the issue because this is implied, and because it is implied many commentators still believe it might be denied.

You talk about the copyrighting of tags in graffiti art. What is the legal distinction between art and writing when it comes to graffiti?

In my opinion graffiti is art. Not all tags though. There are awful tags that are quite simple, especially the ones painted or drawn by ‘toys’ – in graffiti jargon, this means the inexperienced writers, the teenagers who are just starting out. It takes years to perfect, to evolve, to learn how to write the tag. It’s a career that takes years to develop. I think tags and graffiti writing are a kind of calligraphic art. The problem is that whilst fine artists train on paper, writers train on our properties and our walls and they enrage many people.

Do you think street artists would want their work to be legalised?

We need to make a distinction between graffiti writing and street art. There is a link between these artistic movements but they are different. The distinction is not straightforward or clear cut because there are many writers who do also figurative street art and many figurative artists who also do some writing so it is not really a clear-cut distinction, but there is a distinction.

Regarding whether street artists would want their work to be legalised – not all of them. I have interviewed many, especially writers but also street artists, who get their adrenaline boost by painting illegally. They wouldn’t get the same adrenaline rush if they painted legal works. There are also studies which confirm that the adrenaline may give the piece more of an artistic edge, but this is controversial, because on the other hand when you paint illegally you need to be quick, and when you paint quickly you may sacrifice artistic perfection.

It’s interesting that you pick up on the desire for artistic recognition amongst street artists and you suggest that it’s a right that should be protected. What do you think are the essential qualities or rights of art that are being protected in copyright law? Is it about the financial value of a piece? Is it about the right for an author to be named as the author of the work? Or is it about the right for the art to exist in the first place?

It’s a mix of all of these factors I think. For sure, copyright is not a trigger that pushes artists. They don’t start painting walls or trains because they want to claim royalties. Increasingly however, once they create the work, some of them – not all – express and show interest in some forms of protection. Especially when there is commercial exploitation by someone else, or someone tries to steal their works by passing off their works as their own. After a violation occurs, they might show more interest, rather than before it happens.

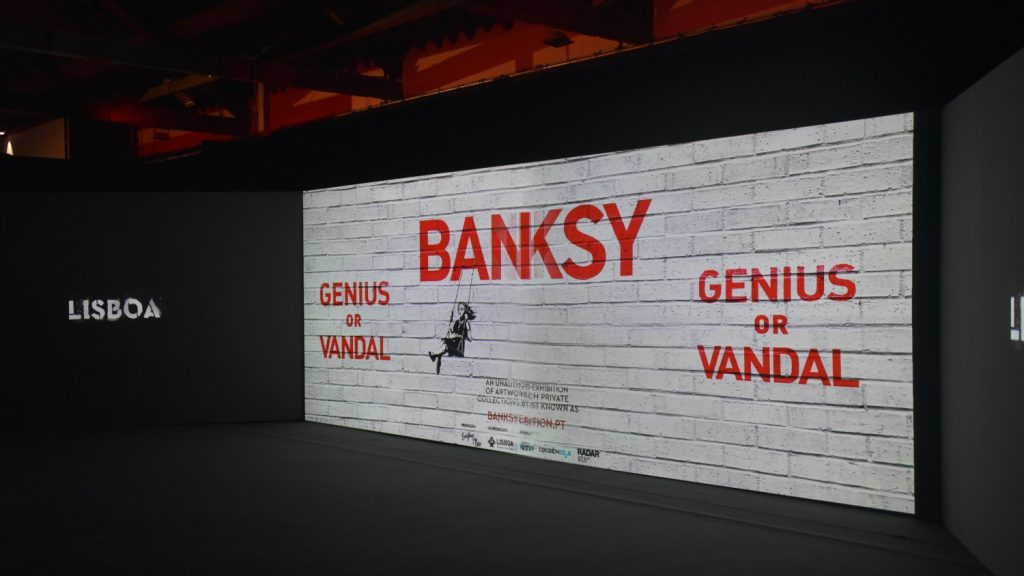

Everyone thinks about Banksy when they think about street art. In his famous Girl with Balloon, now named Love is in the Bin, the art work was changed by an in built shredder as soon as it was sold in the auction chamber. Do you feel his art is a direct response to some of the legal questions that surround art and copyright? Was the artwork a different entity before and after the shredding?

What happened in that auction house was not really due to copyright. I think Banksy wanted to create some sort of interest around his art, and as you know the value of the art doubled, from one million to two million. And many think that probably the auction house might have already known that, and so this was a kind of organised prank. We will never know. So it was not really a legal issue. But what Banksy did there is to create another work, because after the shredding he gave another title to the artwork. It was the normal Banksy prank. He wants to surprise and create interest. Banksy is also surrounded by many creative people who give him ideas. He has ideas himself of course. But it’s an industry and there are many people around him helping. For example, as far as I know Banksy does not go any more to paint in person. He just has the idea, and then sends his people to do the stencilling on the street. As least that is the rumour.

You comment on some famous cases like the 5 Pointz case where the rights of artists really come up sharply against the rights of property owners. It’s interesting that the artists involved in that case weren’t able to get an injunction to prevent the property owner from knocking down the site but they were able to sue for damages after the event. Do you see the law changing or progressing in the future?

That was a revolutionary ruling. A decision which firstly will probably change and has already changed the perception of the general public of the outsiders – not the insiders – of graffiti artists and their artistic merit. The judge in the 5 Pointz case was very clear (have a look at the US Supreme Court declining the appeal in October 2020) . He said the artists reached the requirement under US law, the VARA, to get protection against destruction, or compensation for illegal destruction. So for the first time an American Judge granted the VARA protection to a graffiti artist, with a huge amount of damages – $6.7 million – the highest VARA damage award in 30 years. The VARA was introduced in 1990 as the Visual Artists Rights Act, which protects the moral rights of the visual artists in America.

It’s a turning point for the community. There are also some writers – hardcore writers – who don’t like that. They told me ‘I wouldn’t have started the action – graffiti is ephemeral. They have just won a case that they shouldn’t have started.’ On the other hand, I have interviewed many other artists that do support that action. So, I think the subcultures are experiencing an evolution from an ephemeral form of art to a less ephemeral form of art.

I cannot say that all artists have an interest in copyright and in moral rights. But there is an increasing interest, so something is moving. It’s different from 30 – 40 years ago when it all started in New York at the beginning of the early 70s. At that time no one was interested in copyright. But, year after year, this changes, especially in the lifetime of an artist’s career. In the beginning there may be no interest; then as she grows up, career opportunities come along with the need for economic recognition. Artists have families and need to put food on the table and support their art projects, so they may look at copyright as a way to support their career.

You worked as an IP lawyer for many years. What was that like? What makes it different from practising in other areas of law?

Before 2009-10 I was in private practice, doing IP law as an IP litigator. Now I am teaching and doing research on the same area, so I changed the work from practical to more theoretical. The difference is the lifestyle. Now I am an academic – I study and do my research. Before, I was giving legal opinion in an environment which was a typical law firm one, with long working hours and weekends. It was very rewarding not only financially, but also personally. I also had huge personal development because I worked with very important, experienced and skilled IP lawyers, and now I can use that experience in my own academic work. IP is a living law, it is not legal theory. I feel my students like my practitioner’s perspective. I bring my 10 year’s experience in the court room, and that’s valuable.

If you wanted to give advice to someone who was interested in practising in the area of IP law what would you say?

Go for it! Because it’s a lovely area – the best area! I am a bit biased here! There is no way you cannot get passionate about it because it’s so specialist – so many areas could be trademarked or subject to copyright. It’s a living branch of law – we are surrounded by IP. There is statistical data that shows that in countries like the UK, the average person comes across 1200 brands knowingly or not, consciously or subconsciously. That’s the beauty of this subject – IP surrounds us, even if we don’t realise it.

Outside of academia, what are your interests?

Family, and music. I collect vinyl.

Do you have a favourite piece of street art?

I like Stik. If you go around East London you will see his stick men, women and children. For example, Big Mother was a huge artwork in Acton. You could see it from the Piccadilly line train to Heathrow. Around the building was a big redevelopment programme of housing, and Stik wanted to denounce this. So you can see the stick mother with the stick kid looking at the redevelopment in a scared way, because this redevelopment was threatening their own life. He was representing the fears and concerns of the families. If you think of the lines and eyes, it is just two points and two lines, but the way he painted them is incredibly expressive, because you can see the fear on the child, attached to the mother. The mother has a kind of expression as if she is giving up. She is looking at the redevelopment around her. Her arms suggest she doesn’t have any hope.

It was knocked down two years ago, so it lasted for 4-5 years. When I spoke to Stik, he said that the destruction is part of the artwork – what they were fearful about was the building being knocked down, so its destruction is the circular conclusion of the artwork.

What’s your favourite museum or gallery piece?

Take a Rest is a canvas from Banksy from a 2009 exhibition at the Bristol museum. I like it because it shows the willingness of the people represented there to get out of there and experience another life together with the viewer. It brings the canvas closer to the viewer.

If you weren’t a legal academic, what would you be?

Marine Biologist or a musician.

Many thanks to Victoria White for crafting such an excellent set of questions – some really interesting aspects of Enrico’s work for us to focus in on.

Victoria is a GDL student at City University. Her current interests include Public law, Education law and Intellectual Property.