‘The common law should no longer recognise the hereditary of a vegan-scone-eating-tree-hugger!’ Sarwan Singh, an esteemed academic, part-time reggae band member, and full-time Senior Lecturer at The City Law School bellowed to the court. The public gallery – a room of fifty or so eager law students – snickered as Singh turned to the judges, placing careful emphasis on each of his words. ‘There is a crisis here in terms of the development of the law! We have reached the crossroad where we have to decide whether parliament is supreme or whether the monarch, at their whim, can decide to stop the parliamentary process!’

The Rt Hon Sir Daniel Wilsher peered over his half-moon glasses in shock and spoke softly. The gallery, at the edge of their seat, leaned in. ‘Are you suggesting that our monarch, King Charles -‘ ‘Correction, Your Honour: King James,’ clerk Patrick Goold interrupted sheepishly. ‘Err, yes, thank-you,’ the judge said uncomfortably. ‘I mean King James would act on a whim?’ More laughter ensued from the gallery.

Drama, suspense, and at times, sheer mockery.

Three words to describe the Staff Moot at City University on 22nd January 2020. A moot competition is a mock court hearing where participants (usually law students) present an argument for either side of an appeal in the form of written submissions and an oral argument. Usually the judges are peers at a later stage in their degree, or teachers, or even (in more prestigious moots) real judges with an actual claim to fame in the legal world (yes, there is fame in the legal world *cough* Amal Clooney *cough*). Moots provide students with an opportunity to perfect the ‘art of persuasion’. Typically, the problems have elements relevant to current issues and provide a valuable opportunity for education. Mooting however, is not for everyone. In the words of the Secret Barrister, ‘the attraction to an egotist with a desire to hold centre stage [is] a description applicable to the near entirety of the Bar’. The same can be said of those future lawyers who practice their advocacy through mooting.

The facts of the Staff Moot written by Ryan Stones, the co-director of the LLB Programme (known for his quick wit and incredible fashion sense), were as follows. A climate change activist group called ‘Apocalypse Now’ were protesting in central London. Their symbol (a globe on fire) became widely recognised and allowed protestors to come together quickly. The UK government wanted to minimise disruption to London commuters and introduced The Congestion Streamlining Bill 2019 into Parliament. It passed through the stages in parliament and the final step was for the Monarch, King James, to provide Royal Assent. King James (the fictitious defendant) refused Royal Assent as the bill ‘severely restricted freedom of expression’.

There were suspicions around whether the King’s motivations were political as he had been seen housing the activists and had long been an advocate for environmental protection and conservation. The issue before the court was whether the prerogative power of granting Royal Assent could be used to prevent Bills supported by the Houses of Commons and Lords from being enacted as Acts of Parliament.

A Brief History

Prerogative powers are powers that formally belong to the Monarch exercised through cabinet. They can be exercised without formal approval from parliament though. There is an informal separation between ‘ministerial’ prerogatives and ‘personal’ prerogatives that dictate who exercises the power. For example, the ministerial prerogative power of granting of passports is exercised by a government department. The appointment of the Prime Minister, on the other hand, is a personal prerogative power exercised by the Monarch (on recommendation from parliament and convention). Royal assent is considered a personal prerogative, however the last time this occurred personally was by Queen Victoria in 1854. It is now granted by the Monarch signing letters patent with the Great Seal of the Realm. Many prerogatives have been abolished over the years or superseded by statute.

The Staff Moot touched on three historic principles that underpin the UK constitution: the ‘Separation of Powers’, ‘Parliamentary Sovereignty’, and the ‘Rule of Law’. And the meticulous balancing act between the three. For anyone who has just finished their first year Constitutional Law course with John Stanton, these concepts have been tattooed onto your brain and I apologise for painfully bringing it up merely two weeks after our final exam. In an interview with Sarwan Singh following the Staff Moot, he believed ‘the time has come in a mature democratic society to deny to the Monarch its hereditary prerogative powers which are a historic anachronistic anomaly.’ The anomaly being the second limb of Dicey’s conception of the ‘Rule of Law’ – no man or woman is above the law. Including the Monarch.

This becomes important today as we start to question the role of the Monarch, their ostensible power over the legislative process, and the courts’ function when reviewing their actions.

Recent examples where the courts have stepped in include the case of R (Miller) v Prime Minister [2019] UKSC 41 where the issue was whether the advice given from the Prime Minister to the Queen that parliament should be prorogued was lawful.

The courts decided it was not. To quote John Stanton, ‘the courts intervened because constitutional principles were at stake’.

The Monarch

The Monarchy is supposed to be a face of stability, preserving the national identity, unity, and pride of the United Kingdom. It is essential they are politically impartial and of good moral standing in order to maintain the confidence of the public. Issues such as Prince Charles’ letters to government ministers, Prince Andrew’s relations with US ‘alleged’ sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, and Prince Harry’s resignation from the Royal family (you may be familiar with the term ‘Megxit’), force the public to question the purpose of the Monarch and its existence within the UK. It is worth noting that this is not some new fad created by the anarchic youths of today. It has been discussed and debated amongst friends, in tabloids, in classrooms, amongst politicians and so on. Mirroring the public, a slow departure of powers that remain with the Crown have filtered through parliament and the courts. As such it has now been creatively woven into our Staff Moot problem by Dr. Stones.

In addition to the concern of whether the prerogative power of Royal Assent was lawfully used, the confidence of the King was also challenged in the Staff Moot. The claim focused on the King’s duty to act without political influence from his ties with the climate change activists. Parallels to reality can be drawn as Queen Elizabeth’s long-standing reign will inevitably come to an end. Though the Queen has successfully remained politically impartial, the line of succession invites Prince Charles on the throne next – can the same be said for him? If the head of state has undue political influence should the Monarchy still hold power over the legislative process? Thankfully (as seen in the case of Miller) we can rely on the courts to keep the state in check and continue to review the arbitrary use of power.

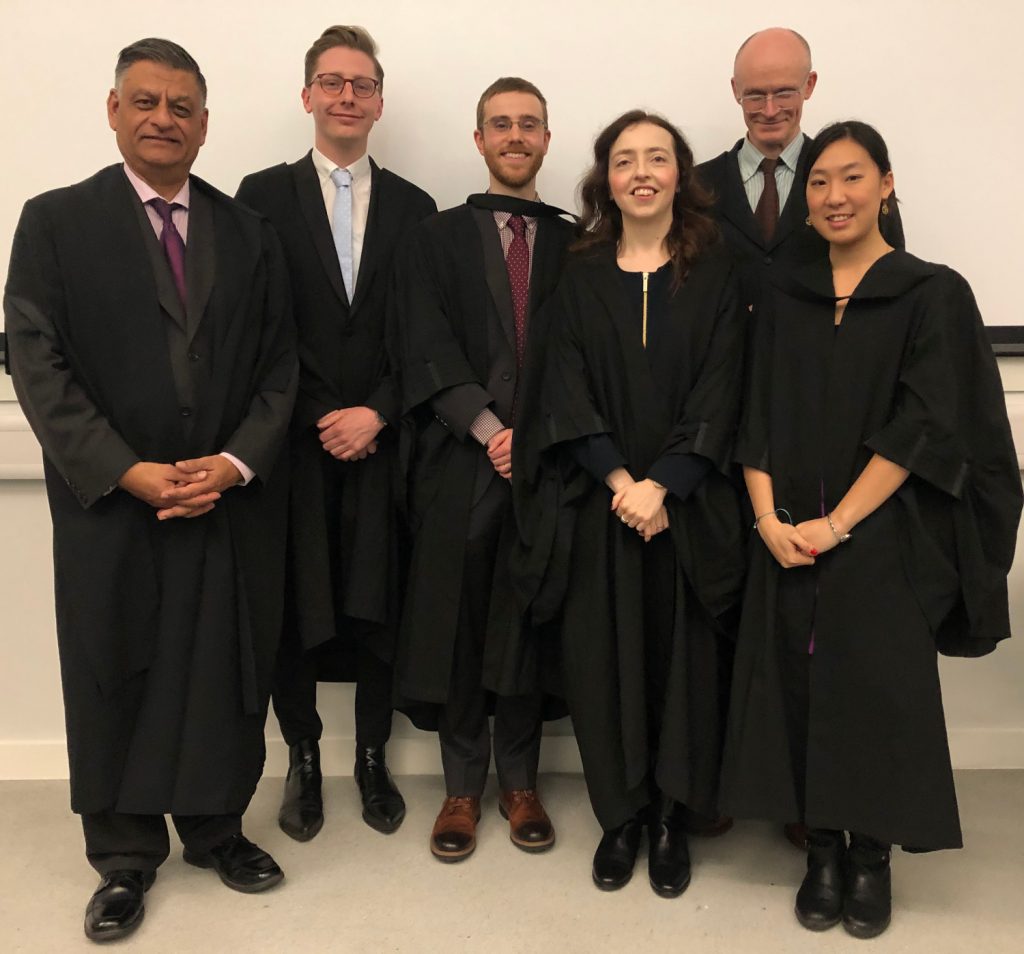

Following approximately thirty minutes of mooting, Sir Wilsher, Dame Yong, and Dame Kendrick exited the court to deliberate.

The court stood upon their arrival and Wilsher made his ruling. ‘Is it justiciable? We find in favour of the claimant and do not accept that Royal Assent is purely a personal prerogative.’ And further, ‘Did King James exercise his powers unlawfully? We find in favour of the defendant. We do believe the monarchy is standing up for the fundamental interests for society and that the refusal was not done on a whim”. The gallery clapped and the façade of the moot slowly peeled away. The mooters stripped off their robes and low and behold, our teachers were standing in front of us and the four walls of the classroom appeared. Gone were the judges. Gone was the courtroom.

It’s not every day we law students get to watch our teachers stand before us and debate with one another. We watched a moot problem come to life and drew parallels with the world today.

Though it is a pretend court with a pretend issue, real education from a moot problem is certain. From the injured worker to the human rights activist, the issues are never-ending. With all this practice, who knows, maybe someday it will be one of us who has the privilege to represent the underrepresented and argue for justice in an unjust world!

Many thanks to Mel Dubé (LLB1 student and Lawbore journalist) for this fantastic review of the inaugural Staff Moot – no easy feat to convey the spirit of such an event in writing!