Monday night, a small lecture theatre in Kings College London. The talk, which had drawn even Lady Arden to the audience, was given by Marc Jaeger, President of the General Court of the the EU. Having joined the Court in 1996 and appointed President in September 2007, Mr Jaeger made a point of not talking on behalf of his office. His talk broadly split into three sections:

Definition and current landscape

Accountability, which is the expectation that actions or decisions will be justified, is expressed by Mr Jaeger through ‘indicators’ in the context of the CJEU. These are: the resources available (both to the Court and to litigants), the workload of the Court, the length of proceedings, and the quality of services for parties and citizens. While these factors are only visible at the supranational level, they can all be influenced by both EU and national reforms.

There are already a number of institutional frameworks that monitor the courts of Europe, for example the European Commission produces a report called the EU Justice Scoreboard each year, and the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) – an organ of the Council of Europe – publishes biennial country reports. An organisation called the European Network of Councils for the Judiciary (ENCJ) is a forum for the national judiciaries of the EU, and puts out an annual report. Each of these has a different scope of review; the CEPEJ for example covers many more countries (47) than the EU (28).

Internal changes at the CJEU have improved single indicators. For example, having smaller benches deal with more minor cases, coupled with a doubling in the number of judges from 28 to 56 (“reform of the judicial architecture”) has decreased the workload of individual judges. Increasingly comprehensive annual reports have improved the quality of services. Finally, the use of electronic documents through the online ‘e-Curia’ portal and a general push towards paperless justice have improved the speed of proceedings in the General Court from 25 months in 2006 to 16 months in 2017.

Mr Jaeger pointed to specific features of the EU judiciary that maintain the Courts’ legitimacy, although this is a slightly different question. A key quality is the secrecy of deliberations which, he claimed, means that external actors cannot have access to documents at the deliberation stage and therefore cannot be pressured and politicised. It does however seem contrary to the point of the talk, and he mentioned that nobody outside deliberations can tell whether specific judges are efficient or not, or what their personal views of a case are. While this may be the culture of the CJEU, many other countries including the UK manage to maintain a legitimate judiciary with individual judges writing opinions.

Other features included the collegiality of the Court – “in this multinational context, this is all the more crucial to the acceptability of decisions”. The selection process was another. Judges are appointed for a term of 6 years and reappointment is possible, but only on agreement of the heads of the governments of the Member States. Judges cannot be reappointed based on their performance or on any other grounds by right.

Multilingualism was also highlighted – an applicant can apply in any language, but the Court needs a common language to deliberate. Cases are translated into all languages, which could be a considerable bottleneck to efficiency. However, he claimed the data shows that translation does not significantly affect the length of cases, and in any case it is important for the accessibility of justice. For a reference of scale, a special report by the Court of Auditors in 2017 stated:

“In the period 2014-2016, the CJEU had a total number of 1.1 million pages translated each year. Between 26% and 36% of translations were done by external lawyer linguists, the annual cost of which ranged from 9 to 12 million euro.”

At this point in the talk Mr Jaeger seemed to have strayed from accountability to legitimacy. It began to seem like an argument for protection of the culture of the Court, which could seem self-serving.

Accountable: for what?

The second segment of the talk segued into what the Court should be accountable for. This more or less restated the indicators of accountability: quality (substantive and procedural), independence and efficiency.

He defined quality as: first, delivering a fair decision, which must not be subject to scrutiny other than by the Courts themselves. He stressed that protecting the independence of the judiciary is a priority. If judges were to face immediate repercussions as a result of their decisions, it would undermine their function. This was a recurring theme of the night. The clarity of judges’ reasoning, the logicality of opinions, and the number of successful appeals also fell into this category. Second, legal certainty – the foreseeability of decisions can be assessed through the consistency of the case law, which forms part of the quality of the judiciary, and the other side of the coin to successful appeals. Third, access to justice. He emphasised that this goes beyond the right to an effective remedy to measurable aspects such as the availability of legal aid, communication with the parties, and electronic access to documents and the Court. It can also be assessed by the ease of the public to get knowledge of the case law. Lastly, quality means wider procedural guarantees including equality of arms and other results of policy. Mr Jaeger said that these aspects should be assessed by the Courts themselves and that it was currently the job of the Vice-President of the Court.

As for independence, the procedure for appointing and dismissing judges, the length of terms in office, the allocation of financial resources to the Court, and the allocation system of cases inside the Court were the four subsections to monitor. In the case of the CJEU, judges are appointed for renewable six year terms, must be ‘chosen from persons whose independence is beyond doubt’ then voted on by the Member States, and can only be removed by a unanimous decision of the judges and Advocates General.

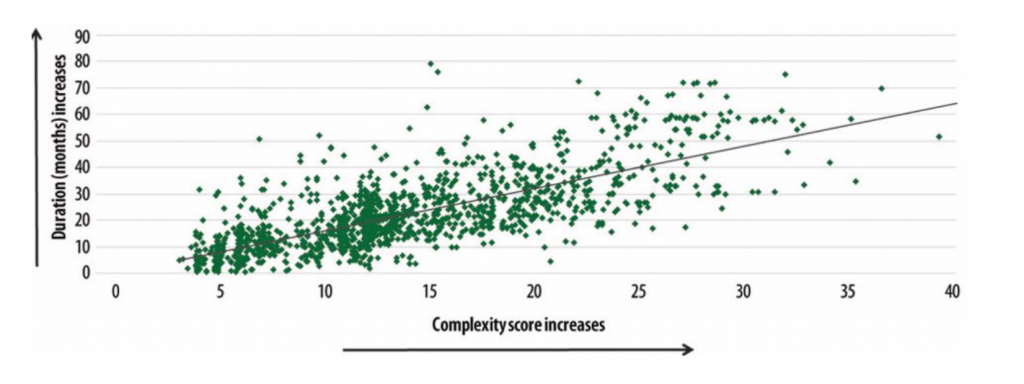

Finally, Mr Jaeger’s favourite topic: efficiency, which of course is a valid goal in itself (“justice delayed is justice denied”). In addition to the external reports already mentioned, there are ‘internal monitoring instruments’. Cases are followed on an individual basis by the Registry of the CJEU, both Presidents of the Courts as well as various meetings in chambers. These cover the duration of different stages of the procedure, the time it has taken to fix a hearing as well as the duration of the deliberations. The result is a lot of data, which can be found in the form of reports, graphs and statistics online, such as the example below from the aforementioned special report, showing duration of proceedings against complexity from cases closed in 2014 or 2015:

The third section of the lecture moved onto who is and should be responsible for holding the Court to account. There are four parties that he highlighted, starting with the Court of Auditors, who produced that special report in 2017 titled ‘Performance review of case management at the Court of Justice of the European Union’. Apparently this was commissioned as a comparative study between the CJEU and national supreme courts, however this got lost as it was developed. Mr Jaeger claimed that it stated the lack of access to documents concerning deliberations had hampered the report, although a reading of the text suggests that they were respectful of the Treaty obligations – “The secrecy of deliberations is a principle of EU primary law … to disregard that principle would lead to a breach of the oath taken by the Judges and the Advocates General when taking office”. It also recommended greater use of IT systems to reduce the duration of proceedings.

The second party was the European Parliament, who holds powers over the budget, and goes through a ‘discharge procedure’ to approve it following advice from the Council of Auditors and the Council of Ministers. This makes the Court financially accountable, presumably in terms of efficiency rather than restricting the budget as a threat.

Third, the Article 255 Committee, which considers candidates for judicial office. This is composed of ‘seven persons chosen from among former members of the Court of Justice and the General Court of the European Union, members of national supreme courts and lawyers of recognised competence’. The involvement of external actors increases accountability.

Fourth, and most importantly in our speaker’s opinion, was the CJEU itself. Here he leant into the microphone – “If you only take one thing from this talk, it is that the courts’ values and the functioning of the courts are important when considering accountability”. This, he said, was his central message, that the courts should and do effectively self-regulate. The Court must decide how to balance its objectives; in this case the speed and quality of decisions.

There was a fifth party lurking in Mr Jaeger’s reasoning – the public. Several guarantees enshrined in the EU system such as the public nature of judgements, requirement for reasons, and availability of an appeal are familiar democratic processes (“The monitoring of judges is given to the judiciary in the majority of Member States”). This might have been a reason for his straying onto legitimacy earlier in the talk.

Close and questions

Mr Jaeger closed by saying that accountability is a tool to fight populism, and what an important time it was for Europe. He stayed for an extra half an hour to take questions. These have been paraphrased below.

Is the Court looking into AI to improve efficiency?

It is but it’s only at the very early stages of doing so.

Why is the legislative process different from the judicial process regarding the secrecy of deliberations?

There are other criteria at the legislative level. For the Court, protection at this stage is important. He expressed worry about deliberations being discussed in the press and online. He pointed to the problem of politicisation in the US Supreme Court.

Is it time to reconsider the method of appointment – is there a question of legitimacy?

No comment on Poland. With regards to the EU, the method is in the Treaty and judges must be nominated by all Member States. Also the Article 255 Committee’s opinion isn’t binding on the Member States but it hasn’t been contravened so far. This filter is “a quite efficient one”. Members of the Committee do thorough investigations. One negative aspect is if the Committee give a negative opinion and the judge is high up in their Member State judiciary this can be difficult for their reputation.

Is there a future for specialised tribunals?

None, for a number of reasons.

What will the impact of Brexit be on the language of court and style of legal reasoning?

It will create work for the court. Apparently someone tried to trademark the word ‘Brexit’.

Has the faster procedure resulted in lower costs for litigants? Is there the possibility of using Skype or similar software?

The costs to be in front of the EU courts are relatively low, and mainly consist in lawyers fees. The EU Court has no influence on this. Applicants do not have a costs problems in general because it tends to be large players at the EU level. He doesn’t think there’s an access to justice issue. He has noticed a decrease in cases from EU civil servants. The costs of preliminary questions are dealt with at the national level. Skype is an ongoing discussion, but he’s not keen. There are difficulties about streaming in different languages and translation issues. Also if proceedings are broadcast will lawyers be pleading to the bench or to the public? He doesn’t want judges to be instrumentalized.

The costs to be in front of the EU courts are relatively low, and mainly consist in lawyers fees. The EU Court has no influence on this. Applicants do not have a costs problems in general because it tends to be large players at the EU level. He doesn’t think there’s an access to justice issue. He has noticed a decrease in cases from EU civil servants. The costs of preliminary questions are dealt with at the national level. Skype is an ongoing discussion, but he’s not keen. There are difficulties about streaming in different languages and translation issues. Also if proceedings are broadcast will lawyers be pleading to the bench or to the public? He doesn’t want judges to be instrumentalized.

Many thanks to Matthew Manso de Zuniga, a student on the LPC at The City Law School for this detailed review of the CEL’s 44th Annual Lecture at Kings on 19th November 2018.