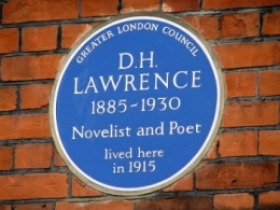

Fifty years ago, on 2nd November 1960 at courtroom number one of the Old Bailey, a remarkable and brave jury acquitted Penguin Books of obscenity for publishing an uncensored version of D H Lawrence’s wildly controversial novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. This landmark decision revealed the extent to which opinion about freedom of expression underwent a remarkable transformation during the ‘60s, challenging the stuffiness of ‘the establishment’ and saving one of the twentieth century’s most significant works of literature from vilification. Fifty years on, Geoffrey Robertson QC was joined by Helena Kennedy QC, Jeremy Hutchinson QC and Ben Silverstone at the London School of Economics to discuss the trial of the novel once branded ‘the foulest book in English literature’.

Fifty years ago, on 2nd November 1960 at courtroom number one of the Old Bailey, a remarkable and brave jury acquitted Penguin Books of obscenity for publishing an uncensored version of D H Lawrence’s wildly controversial novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. This landmark decision revealed the extent to which opinion about freedom of expression underwent a remarkable transformation during the ‘60s, challenging the stuffiness of ‘the establishment’ and saving one of the twentieth century’s most significant works of literature from vilification. Fifty years on, Geoffrey Robertson QC was joined by Helena Kennedy QC, Jeremy Hutchinson QC and Ben Silverstone at the London School of Economics to discuss the trial of the novel once branded ‘the foulest book in English literature’.

The panel was indeed an expert one; each distinguished member bringing his or her own experience to the table, offering a diverse and enriched discussion. Geoffrey Robertson is founder and head of Doughty Street Chambers, the largest human rights practice in the UK and has defended the last two cases brought for blasphemy in this country. Helena Kennedy is a leading barrister and expert in human rights law and member of the House of Lords. Perhaps most interesting of all, Jeremy Hutchinson was junior counsel for the defence in the trial. One of the oldest speakers ever to speak at LSE, his reflections were what made the evening discussion so unique.

Geoffrey Robertson as principal speaker provided the discussion with the history behind the trial which was deployed with his usual impeccable wit and charisma. Censorship for obscenity came rather late to the UK, and it was not until the late 1800s, the height of Victorian repression, that Lord Campbell as Attorney General decided the time had come for obscenity to be punishable in the courts.

The 1868 Hicklin Test for Obscene Libel was the first set of criteria establishing that any book or pamphlet that tended to deprave or corrupt minds open to immoral influences was to be prosecuted. However, there were three main problems with the test. The litmus test for the readership of the work under scrutiny was the most ‘corruptible’ member of society, usually the 14 year-old schoolgirl, and whether she would be ‘depraved’ by it. The work was not read as a whole either – ‘purple passages’ were enough to secure a prosecution, as in the important 1928 trial of Radclyffe Hall’s novel, The Well of Loneliness.

Another problem with the Hicklin Test was that it did not allow for experts to give their opinions on the work in question. As a result of the efforts of Roy Jenkins MP and the Society of Authors, the Obscene Publications Act was passed in 1958 which required the three problems with the test to be remedied. This history was relevant in more ways than one. The prosecution in the Lady Chatterley’s Lover trial had tried to get Rudyard Kipling to appear as a witness, as he had been so helpful in The Well of Loneliness trial. It was cause for great hilarity in the LSE lecture theatre, and revealing of the outdated nature of the prosecution in general, that Rudyard Kipling had, of course, died in 1936.

Throughout the discussion, Ben Silverstone, a former West End actor and now barrister at Doughty Street Chambers, read out passages from the transcript of the trial. This was an ingenious touch to the discussion, quite simply bringing the trial to life. From the satisfied look on Jeremy Hutchinson’s face throughout these excerpts, it seemed that Silverstone perfectly impersonated the ‘sneering, sarcastic’ tone of Mervyn Griffith-Jones, senior counsel for the prosecution. The question, ‘would you approve of your young sons, and indeed young daughters, because girls can read as well as boys, reading this book?’ left the audience in uproarious laughter, as the stuffy, chauvinistic voice of an age gone by was briefly resurrected. Equally, the audience was often left in a captivated and incredulous silence at the sheer audacity of what they were hearing. It was somewhat comforting to be surrounded by the sound of progress, and it was sobering to have Geoffrey Robertson remind us of the utter solemnity that Griffith-Jones’ speeches would have received at the time.

The reflections of Jeremy Hutchinson were perhaps what made the event such a unique one. To have a window into his thoughts in the actual courtroom was both illuminating and quite extraordinary. It was amazing to be confronted with such a rebellious breath of fresh air from the sixties, re-told to us by one of the oldest speakers ever to speak at the LSE. Hutchinson described the man, who, as Hutchinson put it, was the ‘real prisoner’ of the trial. He described D H Lawrence as he sat in the enormous dock at Court One, alone, frail, his red beard, pale skin and sharp, darting eyes, reminding the young Hutchinson of one of Van Gogh’s self-portraits. It was an immensely sad and sensitive description of a persecuted genius, and Hutchinson was keen to point out the irony of the situation that whilst he had defended traitors and fraudsters, murderers and rapist, he was unable to quite believe how he now had to defend this poor, tortured man.

Hutchinson also recalled his fear that just one of the jury members might agree with the barrage of criticism D H Lawrence’s work had been subjected to – ‘an outpouring of evil’ and a ‘literary cesspool’. Back in 1960 there was no such thing as majority verdicts, and if just one juror had agreed with these sentiments, the outcome of the trial might have been very different indeed. There was also a provision at the time of the trial that any case of a sexual nature would automatically have an all-male jury. The defence successfully challenged this, to procure three women jurors. In the opinions of the senior counsel, Gerald Gardiner and his junior Hutchinson, women were far more relaxed and sensible in dealing with sexual matters, and of course, as Lady Chatterley’s Lover had been written from a woman’s point of view, this seemed both an ingenious and revolutionary aspect to the trial.

The most moving part of Hutchinson’s speech, however, was how it ended. His casual humour left him, replaced suddenly, with an unbridled passion. ‘What’s wrong with this country of ours?’ he questioned us angrily, hitting the lectern in front of him. ‘Why do we still flounder around in our embarrassment and our treatment of sex … nobody can and nobody ever will know what one human being feels for another human being in the privacy and depth of their own heart.’ It was the highlight of the evening to see this remarkable elderly gentleman telling us to ‘grow up and calm down’, slamming The Times for typing four-lettered words with asterisks, and brandishing the Church as an institution torn from head to foot by its humiliation of women and homosexuals. He sat down to the sound of prolonged, thunderous applause.

The acquittal by the jury was momentous. They were out for less than three hours and the trial itself saw three million copies of the novel sold within the next three months. The trial represented a break away from the old, out of date ‘establishment’; one that had time and again proved itself to be sexist, snobbish, and completely out of touch with modern opinion. Penguin Books were attempting to make great literature available to ordinary people of all walks of life. Whilst the prosecution crudely invoked the idea that it would be dangerous for this book to be in the hands of women and the working class, the decision of the jury symbolised the resentment at the ‘pin-striped folk’ who ran everything.

The witnesses called for by the defence also highlighted a shift in public opinion, perhaps the most remarkable being that of Richard Hoggart, author of The Uses of Literacy, who effectively remarked that he believed four letter words to be totally characteristic of many people, not only the working class. Indeed, D H had Lawrence had simply wanted to re-establish the proper use and meaning of the word ‘fuck’. These aspects of the trial were what Helena Kennedy elaborated on, and went on to warn us that the battles around freedom of speech continue today. Whilst the trial in many ways marked the beginning of the victory of liberal humanitarians, as Gerald Gardiner became Labour’s Lord Chancellor in 1964 on conditions such as banning the death penalty and adultery as a matrimonial crime, in 1988 Penguin Books was called in 1988 to defend a prosecution charge made by the Ayatollah’s fatwa on Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses.

Overall, the discussion was a spectacular and unique event. The length of the discussion was rather long, leaving no time for questions. Yet no part of the discussion could have been left out, and indeed, a further discussion on freedom of expression in today’s society, discussing more fully the implication of Rushdie’s novel and Robertson’s own experience of defending Catholics’ rights to campaign against abortion during elections would have been welcome. Despite this, it was a great honour to hear such wonderful speakers, sharing the views of a passionate man, whose beliefs that an industrial society based on money and materialism had destroyed the natural intuitive side of love and life, nearly resulted in his work being prosecuted. Perhaps the loveliest touch of the evening was reference to a letter written by a woman who had been a 14 year-old schoolgirl in 1960 to the Guardian newspaper. She wrote that whilst she and her class full of girls at school had read the book, her only wish was that more boys had read the novel. This indication that the novel could have a useful influence on young people about the value of genuine expressions of love, seemed to sum up just how wrong the prosecution, back in 1960, had got it.

Thanks very much to Future Lawyer’s events reporter Felicity Capon, studying on the GDL at The City Law School.

Want to find out more about the Chatterley Trial? Read Geoffrey Robertson QC’s piece, The trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in the Guardian. The BBC have made available a useful timeline to accompany the trial’s anniversary.