On Friday 14th February Oliver Winters and I made our way down to Bath. It was not, however, a romantic valentines weekend away but a trip to compete in the Bristol Inter-Varsity Moot. Other than a brief interval for dinner with my parents we would spend that evening locked away in a spare room at my home, applying ourselves to the ‘finishing touches’ of preparation for the moot. On arriving the next morning we felt we had an early advantage in that other teams had travelled from as far as Essex, navigating London and the flooded south of England on the way. The minor commute from Bath gifted us with valuable hours of extra sleep.

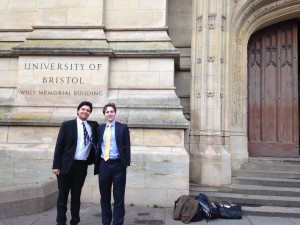

A full energy tank was certainly needed for this moot. The competition would run its course in just one day. Each of the fourteen competing universities would partake in two rounds in the morning, following which the highest four scoring teams would proceed to the semi-finals after lunch. The finalists would then thrash it out in front of a panel of judges including Lord Justice Toulson and two barristers from Bristol’s St John’s Chambers, with a mini at the said chambers as spoils for the winners. With Toulson having first taken tenancy in Bristol, later to be Presiding Judge on the Western Circuit (1997 to 2002), the competition was a thoroughbred West Country affair. The impressive Wills Memorial Building of Bristol University was an excellent spot for it. Having thought we had done well to get there on time, Oli and I would later be humbled to discover the whole event, professionally done from start to finish, was put on by a handful of Law undergraduates!

The moot problem concerned actions in the torts of negligence and battery. Both were brought by a chap called Tony against his friend John. They had been out drinking together and in order to get home broke into and stole a car. John drove, and thanks to his intoxication duly crashed. This caused Tony head injuries that led to his becoming increasingly aggressive and violent following the accident. Unfortunately, Tony subsequently got into a dispute with John over the cause of the accident. A fight ensued in which Tony suffered further injuries! Tony brought actions against John in negligence and battery respectively for these two injurious incidents.

We met the case on its arrival at the Supreme Court, both grounds of appeal having been dismissed by the Court of Appeal. This set the stage for recourse to arguments of policy that would be pertinent to arguments on both grounds. A further feature of the competition was that each team had to prepare both sides of the appeals. Our first two rounds would bring us up against some good opposition in the form of the Open University and the University of Exeter.

Oli led our effort with unsurprising strength. He dealt with the first ground of appeal, that Tony’s claim in negligence was not barred because of his and John’s illegal act in stealing the car. He summarised:

This involved the doctrine of ex turpi causa non oritur actio (a phrase which my opponent in the Semi-final took great relish in repeating). In the first round we were appellants; I attempted to argue that for the doctrine to apply the illegal act committed had to be causative of the damage claimed for, relying on authorities such as Joyce v B’Brien (2013) and Vellino v Chief Constable for Greater Manchester Police (2001). I aimed to dispel the opposing argument based on the idea that the public would not wear a criminal succeeding in a personal injury claim for his injuries in the course of his criminal enterprise.

As respondent in the second round I attempted to advance three arguments; that in considering whether the damaged was caused by the illegal act, the court should take account of all the circumstances and not the negligent act in isolation (Saunders v Edwards), that a joint course of criminal conduct might prima facie entail a foreseeably increased risk of injury (Joyce v O’ Brien) [2013] EWCA Civ 546, and that finally the seriousness of their crime and danger to the public inherent in their joint course of conduct should be taken into account in deciding whether the doctrine applied (Pitts v Hunt [1990] EWCA Civ 17, cf. Weir v Wiper).

Following Oli, I dealt with the second ground of appeal; a cross-appeal, in fact, from John against the first instance ruling that he had committed battery against Tony in the course of a fight which Tony had provoked, and that as a result of the decision in Pritchard v Co-operative Group Ltd [2011] EWCA Civ 329 the defence of contributory negligence is not available as a defence to an intentional tort.

I found that the law favoured the respondent to the cross-appeal as it seemed quite clear from a strong line of case law, most recently and succinctly set out in Pritchard, that the defence of contributory negligence is only available to a defendant where, but for the Law Reform Act 1945 (which significantly altered the nature of the defence of contributory negligence, and before which contributory negligence was only a defence at common law), it would have arisen as such at common law. In the instance of intentional torts including trespass to the person, and thus battery, the defence did not arise at common law pre the Act and therefore did not stand as an available defence in this instance.

In the first round I delivered this argument for the respondent comfortably. I was weaker in our second round acting for the cross-appellant. It seemed clear that the cross-appeal should fail because contributory negligence was not available as a defence to the tort of battery at common law and therefore not available here. There was some case law that enabled argument to the contrary, but this was to rely primarily on the obiter of Lord Denning (always a precarious place to be) and required some awkward fact-distinguishing in order to make the case that contributory negligence might be available on these facts where the claimant’s contribution to the tort was as slight as Tony engaging in a dispute with John. There was no precedent, not even foundation in obiter, for the availability of contributory negligence on such thin grounds with respect to the claimant’s fault.

Somewhat to our surprise we found out at lunch that we had made it to the semi-final. Here we would meet BPP in front of a panel of three judges, two of which were barristers of St John’s Chambers, one a Bristol-based solicitor.

In the semi-final Oli was to appear as appellant (me as respondent to the cross appeal). Back to Oli:

This was the more difficult case to make in theory but sometimes the pressure of being on the wrong side of the law can lead you to a better argument. Unfortunately I was not sure I had one in this case! The semi-final started well enough, seeing as we had had an opportunity already to make these arguments in the first round.

However I found I hit a rather large and insurmountable road block – for all the attempt to show the law was not as clear cut as the respondents might wish to make out, the facts were still rather hard to construe in our favour. Could the fact that the car was stolen really be separated from John’s negligence in crashing the car? More so, how could Tony claim to have no causal responsibility for his injury? It may not be the case that if the car was not stolen they would not have crashed – but the act of theft in which Tony participated was pretty important in turning John from a drunk to a drunk driver. Needless to say the panel judges were quick to pounce on my sophistry, and I felt that I had not really hit the nail on the head when it came to the end of his submissions.

My opponent from BPP began by attempting to lay out the progress of ex turpi causa doctrine from its origins to the present day – however the judges intervened to say that (sadly) we did not have quite enough time for this exercise. However he continued by making a strong argument that the court should not indemnify Tony against such conduct, and relied on authorities such as Gray v Thames Trains [2009] UKHL 33 to put the point that Tony could not recover for injuries as a result of illegal conduct for which he was responsible.

Though I was in my preferred position of appearing for the respondent to the cross-appeal, closer scrutiny from the panel in the semi-final would reveal a flaw in my argument that I had not considered beforehand, and failed to deal with particularly well in the moment. The judges rightly questioned me on the construal of the Law Reform Act 1945 by Lord Justice Aikens in Pritchard upon which I had relied. It was clear, on closer consideration, that Aikens had construed the Act as if there were policy guiding him where in fact there was no such thing. The Act provides that the kind of faults capable of constituting contributory negligence are, ‘negligence, breach of statutory duty or other act or omission which gives rise to a liability in tort or would, apart from this Act, give rise to the defence of contributory negligence’. There was no reason for Aikens, nor the case law he endorsed, to attach as they did a further stipulation to this provision; that fault on the part of the claimant could only be found capable of raising contributory negligence as an available defence where it had been so at common law before the inauguration of the Law Reform Act 1945.

In doing so he was following the strongest and most definite line of cases on the issue since the Act had come into force, starting with Reeves v Commissioner of the Police of the Metropolis [1999] UKHL 35. However, this construal seemed as though there was policy guiding it towards being akin to the Criminal Law, which refuses to allow for an equivalent defence of contributory negligence for any criminal act (except where murder might become manslaughter where there has been a ‘loss of self control’). Yet there was no such policy. Rather, Aikens was following, and indeed consolidating, a mistaken line of authority where, in fact, the statute seems to allow for the fault of a claimant, notwithstanding the context of an intentional tort, to constitute contributory negligence for the purposes of the Act. Though I was able to comment that the supplication to the Act endorsed by Aikens made good sense, not least in light of its semblance to the sensible approach of the Criminal Law on contributory negligence, the judges had exposed a flaw in the legal reasoning behind it which I was not able to justify in the moment.

Sadly our efforts did not prove enough to put us into the final, but we felt we came up against some strong and deserving winners in the form of BPP. They went on to compete in the final against the hosts, Bristol, who were the overall victors at the end of the day. I must admit by the time of the final, which we had been invited to spectate, Oli and I were in the pub toasting ourselves and our moderate success, and of course commiserating with each other with respect to the 2014 Valentine’s Day that, for us, never was. There is always next year!

Big thanks to David and Oliver for representing City at this moot and for sharing their experiences with Lawbore. David and Oli are current students on the GDL programme at City.