Strategic litigation is an emerging topic in campaign and law circles, having as it does the potential to achieve wide social and environmental goals using the law. The idea of ‘movement lawyering’, mentioned at the Reblaw conference in 2018, was echoed by barrister Jamie Burton speaking at the ‘Strategic Litigation’ talk held at Doughty Street Chambers on the 14 March 2019. Jamie Burton’s addressed the question of ‘What is strategic litigation?’ while Jo Underwood, Managing Solicitor from Shelter, provided insight into its practical application by an NGO. In attendance were a number of community-based law projects, such as the Southwark Law Centre, Kensington & Chelsea Law Centre, Public Interest Law Centre, and housing activists from groups like HASL (Housing Action Southwark and Lambeth). Although this particular talk was focused on housing, strategic litigation has much wider application.

Jamie Burton – Barrister – housing specialist at Doughty Street Chambers

Jamie addressed the question: ‘What is Strategic Litigation?’. A definition he used ran something like: “a form of public interest litigation seeking a social or political remedy, that impacts not just the individual claimant but large numbers of people, especially certain groups of people.” Jamie then dissected this definition with barristerial precision, making the points: ‘social or political ends’ was using the law for a purpose it was not necessarily intended, and ‘impact’ must be for the right kind of people, eg those shut out, by ‘giving them a legal voice when they lack a political voice’. In strategic litigation, the goal is established first before the case is devised to meet it and the client is representative of a group of people facing a common problem.

Jamie then addressed the question: ‘How do you become a strategic lawyer?’. His first point was – ‘call yourself a strategic lawyer’(!). Being a strategic lawyer means thinking about the work and cases you do, looking at the big picture, aiming to make an impact, and finally, having ‘big balls’. A strategic lawyer must collaborate within and outside the law, and mobilise, plan and strategise with others, such as NGOs and pressure groups. As a lawyer, this work will need to be done both in practice and on non-billable time.

Part of the planning is deciding who you want to target (‘stopping bad people doing bad things’) and how you go about it. Is it changing the law, enforcing it, getting access to it or raising awareness? Sometimes it is enforcing the law against gate-keepers such as local authorities, or raising awareness of an issue, such as the effect of austerity on disabled people. Working out what it is you want to do is key.

Collaboration is essential. Jamie advised lawyers working on a case with public interest potential to speak to others working on the particular issue, such as NGOs, activists, journalists and bloggers. When developing a public interest case, listen to lived experience, and get THEM to lead. Speak to legal experts working in adjacencies, academics and other experts. Jamie’s advice is: ‘Take everyone with you – win and lose together’. Jamie provided two examples:

- R (Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2019] EWHC 452: an ‘economic abuse’ case, with three NGO interveners, bringing together various specialisms and academics to give expert evidence;

- Cameron Mathieson v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions [2015] UKSC 47 – a case regarding Disability Living Allowance, in which the research work done by a local community group helped provide compelling evidence at trial; an example of ‘getting the evidence which drives the outcome of the case’.

Next is working out a litigation timeline, with what needs to be done and who needs to be involved, recruiting clients and supporters, and working out how to fund the case (eg legal aid, crowdfunding, cost capping, etc – get creative, often fundraising raises publicity in its own right). Last but not least, you need to think how you are going to get the evidence you need. Winning is about ‘evidence, evidence, evidence’, the more compelling the better. Here interventions by NGOs and pressure groups can be useful.

Finally there is fitting the litigation into a broader campaign in order to sustain any results from the case. This is about embedding the legal case into the campaign, by using communication strategies for the key moments in the case, lobbying in Parliament (Early Day Motions, Prime Minister’s Questions) and other forms of campaigning, including direct action. ‘Maximise your current case for its strategic advantage’.

Jamie finally offered some sagely advice to the budding strategic lawyer – ‘focus on the outcome but always aim high’, ‘persevere’, and ‘make your own luck’. Also: ‘it’s meant to be hard and you can’t will all of the time’, ‘sometimes a loss can be a win’ and my favourite: ‘this is as fun as the law gets…’.

Jo Underwood – Managing Solicitor of Shelter’s Strategic Litigation Team

The Strategic Litigation Team (currently 40 solicitors) operates as a law firm within the Shelter Charity. It is a specialist team which has legal persons working locally, assessing issues facing a particular area, and nationally, on research, policy and lobbying. The team starts targeted litigation deliberately and follows it through to post-judgement, with enforcement, media and ‘embedding’ change. Using the law is a key part of Shelter’s strategy to ‘help achieve change’.

Shelter has been involved in litigation in the Supreme Court, making interventions in cases involving housing, homelessness and welfare benefit. Two recent case in particular have been DA/DS & others v Secretary of State for Work & Pensions UKSC 2018/0074 and UKS 2018/0061 (“DA”) and Samuels v Birmingham City Council UKSC 2017/0172 (“Samuels”). These cases are still awaiting judgement.

DA involved challenges by lone parents with children under 5, the claimants alleging that downwardly revised benefit caps were discriminatory because it disproportionately affected lone parent families, the vast majority being women. In Samuels, the claimants was evicted due to rent arrears, caused by the effect of the Local Housing Allowance (“LHA”) freeze on his housing benefit payments. Birmingham City Council regarded Mr Samuels as intentionally homeless and therefore not their responsibility to re-house.

Shelter’s inventions were based on its own research into the effect of the UK benefit caps and the LHA freeze. This research involved sending Freedom of Information Requests to 326 local authorities across the country, modelling data to predict the outcome of the lower caps on lone families, and undertaking a survey of 1,137 private landlords and their attitudes to benefit claimants.

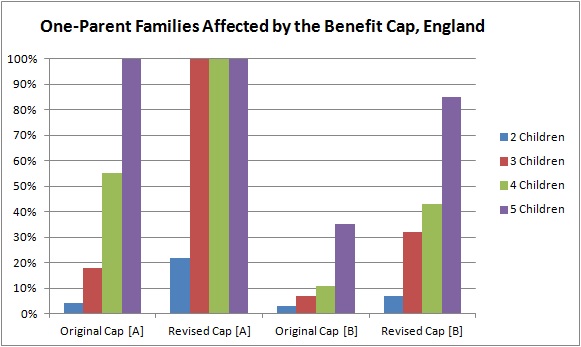

The project group at Shelter collated this information to provide evidence in the DA case. The statistical evidence showed that:

- Even if lone-parent families made changes (eg overcrowding in a smaller home, or moving to cheaper rented areas), they could still not avoid the effect of the revised benefit cap;

- Those affected by the benefit cap had spread from London and the Southeast, to the whole of England;

- The private landlord survey showed the 61% of landlords would not/ would prefer not to let their properties to those receiving benefits.

[A]: Proportion of one-parent families affected by the benefit cap

[B]: Proportion of one-parent families without enough to cover their rent and essential family costs

DA is an important case because it attempts to set a precedent in recognising indirect discrimination against women by cutting welfare benefits. Furthermore, Shelter’s research showed that the DA case only scratches the surface, with discrimination against those on benefits very widespread, its actors including letting agents, insurance companies, mortgage lenders (eg ‘buy-to-let’), etc.

In the case of Samuels, the Shelter project group applied to intervene, their research evidence revealing that the LHA freeze was having a drastic impact on people’s ability to find and keep an affordable home. Shortfalls in housing benefit meant that many people had to meet the shortfall by paying rent out of their already meagre subsistence payments. The shortfall was affecting 95% of areas in England.

Furthermore, Local Authority (“LA”) assessments under LHA were variable, lacked transparency and had no proper regard for the needs of children in the assessments. Of Local authorities assessing affordability under LHA, only 43% provided guidance documents to their staff and only 17 (out of 246) provided staff training. Different ‘reasonable monthly expenditure’ benchmarks were used by different LAs. These benchmarks were developed for debt advice agencies, and vary between 10% – 25% (or £167-£455 per month) from each other. Applicants did not know which benchmark their LA was using to assess their needs or any relevant information to challenge adverse findings.

Conclusion

The ‘Strategic Litigation’ talk at Doughty Street Chambers was a good insight into the discussion currently going on around social- and environmental-justice lawyering, and its practical application. Jamie Burton’s talk demonstrated that being a strategic lawyer is not a science or an art, but an approach to legal work. It requires extra efforts – collaboration, organising and ambition. Jo Underwood provided a good practical example of how a large and established housing charity approaches litigation to achieve its own strategic ends. Following on from Reblaw 2018, the Doughty Street talk was yet another piece in the jigsaw of how to use the law to make a difference.

Many thanks to James MacDonald, part-time BPTC LLM student at City Law School, for this excellent review of this event.