The first Lord Upjohn Lecture was delivered on behalf of the Association of Law Teachers by Lord Diplock in 1971. I suspect the subject of this year’s Lord Upjohn Lecture — ‘Legal Education in the Age of AI’ — would have been rather outside the late Law Lord’s wheelhouse. Yet it seems to be generally understood in the legal world that there can be no head-in-sand attitudes from those in positions of authority. Generative AI is here. It doesn’t appear to be going away. The times they are a-changin.

Personally, I must admit that I’m sympathetic towards the luddite side of opinion. Even though access to Lexis Protégé has the potential to make my life considerably more convenient, I am very wary to use it and wish it did not exist. But that is a kneejerk opinion. The response outlined in this year’s Lord Upjohn Lecture by Professor Lisa Webley was more considered, more cogent, and more clear-headed. Professor Webley is an impressive figure. A legal academic, currently affiliated with the University of Birmingham and the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, she was this year appointed as one of the four Law Commissioners by the Lord Chancellor. However, upon standing to speak in the City Law School’s lecture theatre, she was quick to wryly deflect attention away from her obviously impressive credentials. She laughed off her ‘fulsome introduction’ with clarifying ‘I didn’t provide that!’ and characterizing it as ‘not fair and balanced’ and not in keeping with ‘BBC rules’. She also made clear that the talk to follow would be purely her own view as an academic and would not reflect the opinions of the Law Commission (which had itself issued a short report on AI in July).

She began by examining ‘the nature of the technology’. Professor Webley outlined the distinction between two types of AI systems. She first considered ‘rules-based, top down’ systems, where the algorithm is specifically coded to run in a certain way and the output is explicable. She seemed to conclude that these were effectively harmless and potentially helpful— ‘A bit like having an expert mathematician’. The second kind of system, however, was identified as more problematic: ‘non-rules based’, ‘bottom up’ systems, which immerse the algorithm into a ‘sea of data’ and allow it to construct patterns from it. All the usual suspects — ChatGPT, Copilot, DeepSeek — fall into this category. While not all of these open systems are language based, the most relevant to the law are Large Language Models. LLMs — not, as Professor Webley pointed to some chuckles from the audience, out to be confused with the legal postgrad degree of the same acronym — are potentially dangerous because what they do is not what they appear to be doing.

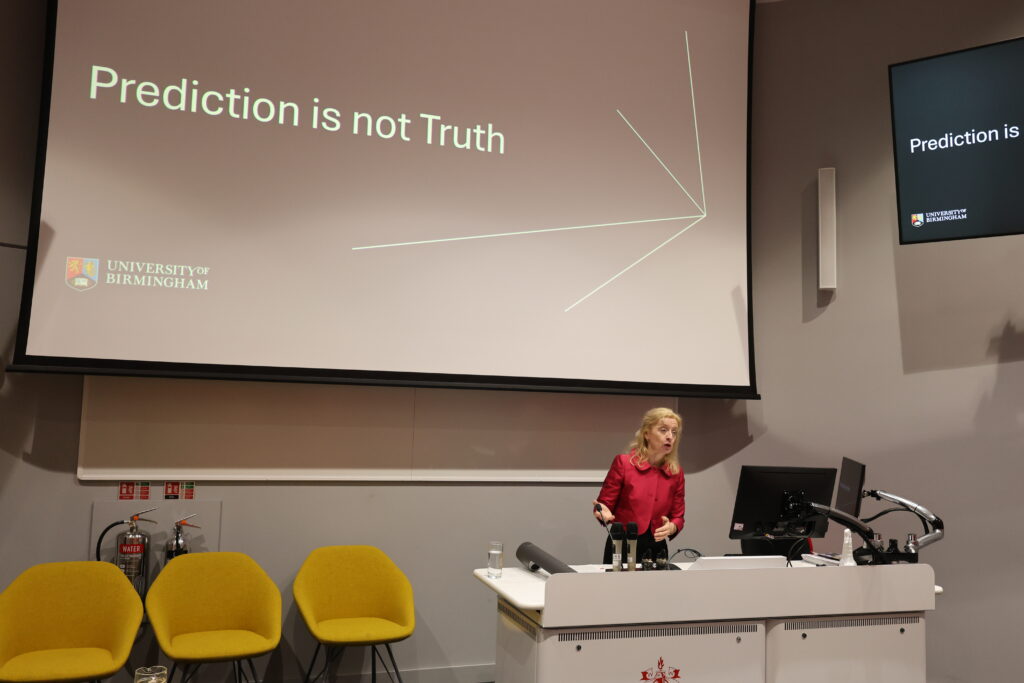

While they may seem to make logical sentences and appear ‘beguilingly human’ in their responses, they are in fact ‘incredibly sophisticated word prediction generators’ fed on vast quantities of texts. As Professor Webley put it, quite chillingly, ‘They don’t understand human language. They don’t understand the words they are generating. They are not truth telling machines’. And yet, they can create an apparently plausible ‘simulation of expert knowledge’.

The results of this simulation, whereby ‘the prediction can predict’ can be humorous. I think it was an inevitable a talk on AI and the law would include reference to the infamous tendency of LLMs to hallucinate non-existent authorities; Professor Webley, playing around with a platform in preparation for the lecture, for herself presented with ‘an entirely new Act of Parliament from 1984’. But the scourge of stories about barristers or students relying on wholly invented case law are extreme examples that obscure the more apparently useful and more potentially dangerous roles that AI has begun to play in the legal world. Professor Webley spent the rest of her lecture examining these roles.

As it was organized by the Association of Law Teachers, the focus of the lecture was chiefly on the impact of AI on legal education. While Professor Webley acknowledged AI might be a boon — and indeed a democratizing instrument — to citizens with no knowledge of the law, who may have better access to a legal world otherwise locked away behind paywalls ad academic libraries, the impact on the academic study of law in institutions of higher learning was taken to be profoundly destabilizing. I must say that, as a student, I did feel rather that I had wandered into the staff room at moments in the Lord Upjohn Lecture: the audience was largely teachers and academics, and the lecture was addressed explicitly to educators. I can’t recall ever being so privy to the behind-the-scenes strategies of the education world. When it came to teaching the law, Professor Webley rightly pointed out that AI has some considerable potential benefits. One possible exercise she imagined involved getting an AI to come up with a response to a specific legal problem, and then to make students critique that response to uncover what the algorithm has missed. She also registered the fact that this is probably not the most significant shift in legal education over the course of her career. The change ushered about by the advent of the digital age makes the world of the past twenty years ago closer to the AI-haunted future than the environment in which Professor Webley was taught the law: she recalled students on her course cutting cases out of Law Reports in the unviersity library for want of a photocopier.

But on the whole, the prognosis was not positive. Professor Webley’s chief concern in the academic context was ‘deskilling’; law students reliant on generative AI to drift through legal courses would be improperly trained in the interpretative skills that study can instill, ill-prepared for legal professions, and conditioned to cut corners and break rules — hardly the cornerstones of legal ethics. ‘Education is intention, plus values, plus knowledge, plus skills’, she declared: ‘that can’t all be generated by AI’.

Professor Webley has written extensively about legal writing, and thus it is unsurprising that she was far more perturbed by the use of AI to produce written work than merely deploying platforms for research purposes. ‘There is something magical in writing’, she declared; in her view, losing command of the written word would fundamentally hinder a student’s intellectual development.

While the impact of AI on educational courses was the chief focus, it was never far from the speaker nor the audience’s mind that the law students of today will become the lawyers of tomorrow. Both Professor Webley in her lecture and several academics in the audience in the Q and A session that followed raised the potential knock-on implications of this de-skilling on the legal professions. What would occur, as one audience member put it, when ‘the last old school lawyer retires’: how could incorrect interpretation be identified if nobody has the requisite interpretive skills? Furthermore, what would this mean for legal ethics? A lawyer plugging a client’s information into an algorithm, as Professor Webley flagged up early in the lecture, is a total violation of GDPR and breaks the bond of trust between lawyer and client. More existentially, this is also a major challenge to the rule of law as such. ‘Law’, as Professor Webley arrestingly stated, ‘is a confidence trick’: it must be understood and maintained by consensus in order to be effective.

The issues identified on that chilly November night were daunting in scale and seriousness. The key problem in responding to the rise of AI is the lack of time we have had to assess its effects; the technology appears to advance too quickly to be properly understood or for a proper response to be implemented. And yet Professor Webley was depressingly upfront about what raising these issues actually achieves: ‘I’ve solved nothing this evening’. And yet she continued, concluding her talk with a joke: ‘I’m relying on you all to have this solved by the start of the New Year’. Well! It looks as if this will have to be a busy month.

Patrick (who everybody calls Paddy) is an aspiring barrister on the GDL at The City Law School with an interest in public and commercial practice. As an English student by training, he is still keenly interested in literature, film, history and politics. He’s also willing to bet he knows more about dinosaurs than anyone else on the GDL (fighting talk!). Paddy is a member of this year’s Lawbore Journalism Team.