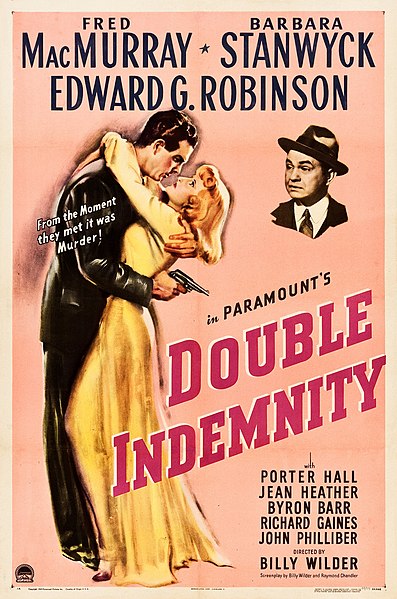

Welcome to our new series on Law and film! Some years ago (..eek! 10 years ago!) we had a series written by one of our teaching team on classic movies with a legal flavour. This year’s journalist team are picking this up again – at the end of last month we had a review of a modern film: ‘Anatomy of a Fall’ (thanks to Yasmin) and now we hark back to the black and white days with Double Indemnity. Take it away Iona…

Double Indemnity (1944) is the tale of a carefully orchestrated murder, premised on the most seemingly banal grounds: accident insurance cover. The premise is that Phyllis, young and beautiful wife to an older, wealthy man (a classic trope if ever I saw it!) insinuates that she wishes to obtain employment cover for him- crucially, without his being aware of it. Mr Neff, insurance broker and protagonist of the story, is immediately suspicious, but this suspicion soon turns to a fanatical wish to help her secure the biggest pay-out possible through his company: a ‘Double Indemnity’.

Double the indemnity is paid out to the claimant’s estate if he is killed in an accident whilst on a train. Phyllis and he arrange for her husband to take a trip, where he will travel on the said train, killing him beforehand in the car, whereupon Mr Neff poses as him, pretending to fall off the train (at a point where the two leave the real body of the husband).

It is intricately planned, and the investigation that follows it as well as the reluctance of the insurance company to pay out so much money, calls to mind the many tort road accident cases, where it is the insurance companies fighting it out, desperate not to pay indemnities to claimants.

The figure of the law in the film takes on wild, psychoanalytically personified form. Theories have drawn an analogy between Keyes, a paternal figure at the insurance company, investigating Mr Neff, and the Freudian ‘Super Ego’ (the conscience or the internalised parent). Neff’s desires towards Phyllis and the killings satisfy the Id impulse.

Keyes is a figure of law and order. His very name (although this, a public law theorist would tell you, might be taking the ‘literal rule’ too literally) positions him as a missing puzzle piece: possessing the ability to unlock, to solve the case. The way he proceeds with the investigation on the basis of what his ‘little man’ or, colloquially, what one might call his instinct or his internal moral compass, can tell us a lot about the legal process. Investigators proceed somewhat on their gut; Keyes reminds us that no matter how much we try to separate head from heart (or chest, in Keyes’ specific case), a lot of what we decide and how we interpret the law will be based on what the ‘little man’, the internal conscience, tells us. This is the explicit premise of a whole branch of the common law: Equity. Could Keyes’ investigative approach even be described as equitable, ancient English tradition rearing its head in Classical Hollywood noir?

Interestingly, even the flirtatious banter of Phyllis and Mr Neff is conducted with regard to the law, what psychoanalysis would call the Symbolic Order. It lurks on the periphery of their conversations, as inconspicuous but ever-present as the slatted shadows of the blinds that line every indoor scene, in the noir tradition. Phyllis, lit softly in the hall, says to Neff, ‘there’s a speed limit’, he: ‘how fast was I going?’. The conversation paves the way for the whole film’s transgressing the legal ‘limit’, both in psychic and actual terms.

The ‘supermarket’ scenes of the film have been extensively theorised upon. Neff and Phyllis stand, lit, unnaturally, in the fluorescent warehouse, whispering furiously, glaring at each other behind dark glasses on the other side of trollies, while shoppers behind and around them glide and swerve. It is so unnatural a setting for a forbidden, post-murder rendezvous: but so natural, somehow, when the setting is something as banal and unshowy as an accident insurance pay-out. It brings, visually, the sphere of American consumerism, with which the initial murder was fundamentally concerned, into the realm of darkness and glamour. It ties the act inextricably to the society of consumption, where the monetary premium on life itself was the reason for the committing of such an act. The film could be argued to act as a critique of the commodification of life in society and in law: law’s endorsement of this.

Keyes is a moral arbiter, but he is within the system: he is rarely seen outside of the carefully desk-lined offices of the insurance company, surrounded by the slatted shadowed blinds which are characteristic of the film throughout. The end shot epitomises Neff’s inability to ever escape society, to get away with transgressing legal limits. He tries to escape, to walk beyond the glass doors of the insurance office that read ‘Pacific Insurance Co’, but opens the door and collapses just outside. He is physically unable to go beyond the boundaries of the Symbolic Order, and when he is handed over to the police, legal order is restored. The film comes down on the side of the law, portraying, in a sense, its omnipotence over the common man.

Iona Makin is a current GDL student, and recent (2023) BA English graduate of Cambridge University. She is particularly interested in criminal law and personal injury. She loves long distance running and cross country, and reading long classical novels and poetry. She is also a (converted) fan of Classical Hollywood, and interested in film theory and visual culture. She is a member of the 2023-24 Lawbore journalist team.