Calling all future international criminal lawyers and international relations fanatics alike!

Something that may be of some interest…

On Monday the 14th of November, a briefing titled, “Russia’s Genocide in Ukraine” aired across the pond. The United States (Congressional) Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), also known as the U.S. Helsinki Commission, wasted no time in making the case that Russian aggression in Ukraine is tantamount to genocide.

The Helsinki Commission is a coalition of leaders from the most powerful areas of the United States government including the House & Senate, the Department of State, and Defense, & Commerce. All of these leaders are hand-picked either by the president or the speaker of the house. That means these people are going to be the best of the best in terms of expertise. The Commission aims to monitor and encourage compliance with the 1975 Helsinki Accords which embrace the inviolability of European frontiers while rejecting the use of force to intervene in State’s internal affairs. The Helsinki Accords also urges signatories to respect fundamental human rights.

The briefing’s expert panelists consist of two historians, one international criminal lawyer, and one Ukrainian human rights activist, listed below.

- Dr. Timothy Snyder, Richard C. Levin Professor of History, Yale University

- Ms. Maria Kurinna, Ukrainian human rights activist; International advocacy advisor, ZMINA

- Dr. Eugene Finkel, Kenneth H. Keller Associate Professor of International Affairs, Johns Hopkins University

- Dr. Erin Rosenberg, Senior Legal Advisor, Mukwege Foundation; Visiting Scholar, Urban Morgan Institute for Human Rights

The following information is a direct quote from the U.S. Helsinki Commission. Humbly, I believe the following statement in full is worthy of quotation rather than a novice summary. The briefing’s synopsis, and foundational argument in favour of considering the war a genocide, are as follows:

“From Russian dictator Vladimir Putin’s 7,000-word screed that systematically and historically denies Ukrainian nationhood; to mass graves uncovered in almost every Ukrainian territory liberated from Russian occupation; to the Kremlin’s public campaign of mass deportation and of Ukrainian civilians and children through “filtration” concentration camps; to the deliberate targeting of maternity hospitals, medical facilities, schools, and basic civil infrastructure; to the widespread employment of rape and sexual violence as a weapon of terror—rarely has genocidal intent and pattern of action been so clearly telegraphed and demonstrated for the world to see. According to the five-point definition under the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Russia has demonstrated clear, notorious, and mounting evidence in all five criteria, even though only one must be fulfilled to qualify as genocide.”

For reference, below is the five-point definition of Genocide under the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

- killing members of the group,

- causing them serious bodily or mental harm,

- imposing living conditions intended to destroy the group,

- preventing births, and

- forcibly transferring children out of the group.

Provided below are some highlights from the ninety-minute hearing:

First, a summary of the opening remarks. The opinion of the Commission is that there is “[n]o topic more horrifying or more urgent than” current Russian aggression in Ukraine. “The physical evidence is shocking enough. But the Russian government’s very public embrace of a campaign of terror and genocide is incredible to behold.” The CSCE notes that Russian president (or in the words of the Commission, ‘dictator’) Vladimir Putin’s handwritten 7,000 anti-historical personal rendition of Russia’s history, released a few short months before the conflict, denies the existence of Ukraine as a nation. The Commission argues this premeditated/preestablished narrative highlights Putin’s eliminationist agenda which has been echoed and advanced by the most prominent ‘Russian mouthpieces.’

The CSCE also made note of the Russian government’s previous wars in Georgia, Syria, and Chechnya where “ethnic cleansing, deliberate and widespread targeting of civilians, torture, and rape were employed widely and purposely as tools of their warfare.” In doing so, they establish a clear and deliberate pattern of behavior from the Russian government. The Helsinki Commission’s aim is clear — stop Russia as soon as possible through continued supply of reinforcements to Ukraine. “Call this war what it is, a genocide.” Congressman Steve Cohen, a respected voice on foreign affairs, describes the United States’ unyielding support for Ukraine as a commitment to freedom:

“…A threat to democracy anywhere is a threat to democracy everywhere.”

Might I add, current support for Ukraine is a uniquely nonpartisan issue in a time of heightened polarization. A hint of cold-war-esque battle between good and evil resonates strongly within Congressmen Cohen’s remarks. But maybe such memories are needed in fueling unrelenting support for Ukrainian troops.

Did the briefing have a slight air of propaganda? One could argue so, with repeated references to the Holocaust. The situation in Ukraine is deeply grave and worthy of international condemnation and action. But, I would warn against placing present-day horrors so cleanly into the box of the past. This can lead to the undermining of the unique atrocities found within this genocidal attack against the Ukrainian people. Notably, commissioners made clear that America has a large role to play, due to their country being “the most powerful in the world.”

Now onto the panelist discussion.

Professor of History, Dr. Timothy Snyder came in hot with some humour to alleviate the tension associated with the brutal conversation ahead. Lightheartedness, however, is not what this panel set out to portray. Snyder begins by articulating the need to show intention in order to legally describe Russia’s actions as genocide. Snyder quickly delved into the specifics of the crimes perpetrated by the Russian Government against Ukraine, more specifically, the women of Ukraine.

Among the many horrors being inflicted, Snyder focused on the female-targeted deportations to Russia and intentional systematic rape. The most gutwrenching, in Snyder’s words, is the forceable transmission of children from Ukraine into Russia. “The Russians, by their own count, have deported around four million Ukrainian citizens, about a tenth of the population.” It is most startling to Snyder that the Russian Government continues to boast and gloat about its own crimes within the territory of Ukraine. As historically, most State actors inflicting genocidal actions upon another group normally try to hide their acts. In his concluding remarks, Snyder stresses that an argument against calling a set of crimes a genocide can always be found. As Genocide is such an evocative phrase, the international community often tip-toes around its use. This “historically unprecedented level of very clear genocidal intent, all the time, in all forms of media”, cannot be one of those moments.

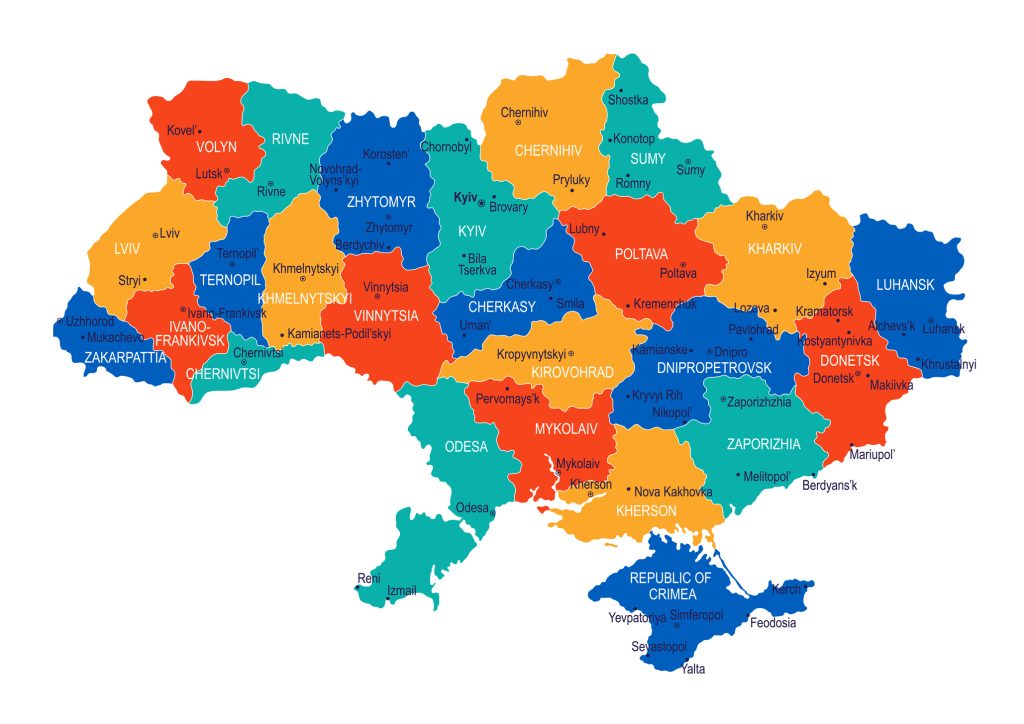

Marina Kurinna, a Ukrainian human rights activist and advocacy advisor, was a Japanese professor in Luhansk before the Russian assault forced her into a life of asylum and advocacy. Her city has now been occupied for more than eight years by Russian forces. Her own mother, a Ukrainian activist, faced persecution and death threats during her work in the revitalization of the Ukrainian language. Kurinna’s own experience with the Kremlin began in 2014 when Russian forces invaded Luhansk. Electricity, water, and gas were cut. Armed street fights became commonplace. In response, Kurinna decided to leave Luhansk temporarily, and at the last moment, her parents refused to join her. In the time it took Kurinna’s father to safely bring her to the train station to flee Luhansk to Kyiv, her mother who had stayed at home was kidnapped by Russian soldiers and tortured. Even while safe in Kyiv, Kurinna received death threats from Russian forces. In her few moments of discussion during the briefing, she stressed, more than anything else, the crucial necessity of American condemnation and proactive action, as it “can set the example for other states to step in and act”.

Professor of International Affairs at John Hopkins University, Dr. Eugene Finkel begins by observing that the question of whether this war is a genocide is still up for debate among senators and civil society alike. “After all we don’t see gas chambers and concentration camps, as in the case of the Holocaust. Nor massive slaughter of civilians in the streets and in the fields as we saw in Rwanda.” Why not just call it a war crime? Why insist on the term genocide? His answer:

“Words matter, labels matter, and how we define this matters.”

It matters politically, legally, historically, and morally. In Finkel’s view, there is no question of whether or not this is genocide— especially if we follow the five-point definition under the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. First and foremost, it is about intent as well as the methods used, “even if not necessarily killing all of the members of a group.” Finkel argues that the Russian government is attempting to destroy Ukraine as a national group. A group that has its own state, language, identity, and its own place in the world. There is plenty of evidence that these actions by the Kremlin are targeted, premeditated and intentional. We know that in communities under Russian occupation, “they came in ready with lists of people that had to be eliminated: local leaders, intellectuals, teachers, and activists. In other words those closely related to the Ukrainian identity.” Finkel then reminds us of the international responsibility to prevent genocide; and that in this case, we have failed. Nevertheless, he argues that we have a moral, political, and historical obligation to do our best to stop this genocide using all the means at our disposal. Ending his remarks by stressing “we should have acted nine months ago. At the least, we can do it today.”

Now for an international law perspective from a senior legal advisor, and visiting scholar at the Urban Morgan Institute for Human Rights, Dr. Erin Rosenberg. She touches first on the hesitancy towards calling the war a genocide within the academic and legal community. She argues this is due to the unusual nature of this event. It is more common to see the phrase ‘genocide’ being used, post-WWII, to define internal conflicts. Specifically, conflicts relating to a minority ethnic group within a country’s territory. The Russian war in Ukraine, however, is a genocide of a national group. In this particular case, Rosenberg maintains that the severity of the underlying acts taken by the Kremlin is not up for question, as they amount to international war crimes. It is, instead, more a question of whether the acts are accompanied by the necessary mens rea. In other words, whether these crimes are committed with the intent to destroy in whole or in part, the Ukrainian people. Under the Genocide Convention, intent must be to destroy the group “physically or biologically, not just to destroy the group’s identity or culture alone.” In this case, Rosenberg is implying that the Kremlin’s actions are imbued with genocidal intent. Bear in mind of course, that such intent can be inferred within the realm of international criminal law. She concludes by urging members of the United States “Congress, and the Executive Body not to try to mimic, or meet the standards that are applied in judicial proceedings in order to consider what the Russian government is doing as genocide within a legislative, policy-oriented context.” Doing so would be inappropriate and somewhat impossible. Rosenberg reminds us that the prevention of genocide, or the halting of ongoing genocide, falls on States, not courts.

What are your thoughts on such an internationally impactful moment?

You can access the briefing in full on YouTube.

Ashley Gate is a master’s in law student specializing in international Human Rights Law. With a previous background working as a medical aid during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic back in United States, she has a keen eye for the intersectional aspects of health inequity. Ashley has a passion for politics, history, and gardening. Ashley is a member of the 2022-23 Lawbore Journalist Team.