Benjamin Burns tell us about his summer experience volunteering at a clinic in Cape Town and at the University of the Western Cape. This is Part 2 of the piece – Read Part 1.

Polsmoor Maximum Security Prison

Before we arrived in South Africa, I was keen to get involved with the group of students who visit Polsmoor, to work with the inmates. Fortunately, we were welcomed by the group, and visited Polsmoor every Friday but one (due, I believe, to security issues at the prison).

The primary purpose of the visits is to teach some of the juvenile inmates about various aspects of the legal system, and the rights that they are afforded within it. With the UWC students, we helped to deliver lesson plans on topics such as plea bargaining, the hierarchy of the courts, and schedules of offences. It is important to note that the visits also allow the inmates to have an extra hour or two outside of their cells. Polsmoor is overcrowded, to the extent that a cell built for fifty inmates often houses one hundred, for twenty three hours of every day.

Our first visit to the prison struck me the most, as we walked through the main cell block to get to the outside space where we would be working with some of the inmates. The experience was an assault on the senses: many of the inmates were screaming, mostly at the female students, and the sights of their faces pressed against the bars was uncomfortable, as was the overall smell of the place.

Similarly unsettling was the mixture of young boys, aged around fourteen, with twenty four year old adults, who were in the juvenile prison because they lacked birth certificates, and could therefore be used to relieve crowding in the adult cells. However, no matter how overstretched the system is, I still cannot believe that, in the juvenile wings, children are placed in cells with adults, especially given the prevalence of sexual abuse and gang violence at Polsmoor.

We were guided through the prison each week by Mr Smith, the head honcho of the juvenile ward. He was unforgettable, in the sense that he was almost a parody of the tough prison guard, with a manner similar to that of Ross Kemp. Jokes aside, it became clear as Mr Smith approached the cells and individual inmates, that they were terrified of him. I vividly remember seeing him approach the door to one cell, and seeing some of the inmates cower back like frightened dogs. At first, I was ap-palled, but after voicing my concerns to Mr Smith, I learned that the real situation was far more complex than I first thought. To explain, the prison system in South Africa is overcrowded and un-derfunded: there are at least fifty inmates to every guard, and many of them are gang members and violent criminals. Accordingly, Mr Smith’s argument was that physical control of the inmates was a necessary evil. Despite my inherent resistance against the idea, I still haven’t managed to come up with an argument that entirely refutes it.

Mr Smith also made his argument in support of the notorious Polsmoor prison gangs, known as ‘The Number’. In essence, his argument was that their values and behaviour is predictable, making it easier for the vastly outnumbered guards to understand and control them. I am far too unfamiliar with the South African prison system, and prisons more generally, to pass judgment, but again, I cannot help but see reason in Mr Smith’s argument.

Our first lesson with the inmates, who outnumbered us by about two to one, was similarly awakening. I went to Polsmoor expecting to find the majority of the inmates to be unchangeably bad, given that they were only in Polsmoor on charge or conviction of the most serious crimes. The reality was that every single one of the inmates was so clearly an unwilling product of their environment, and a society which is still massively hungover from the Apartheid Era. Although there are no longer laws which force black and coloured South Africans to live in segregated areas of extreme poverty, the reality is that, only twenty five years on, most people’s lives are still determined by the colour of their skin. Probably in demonstration of this, I don’t recall seeing a single white inmate at Polsmoor.

It became clear from the inmates’ stories that they had come from an upbringing where extreme gang violence, drug abuse, and poverty was the norm. They were also juveniles. To then hold them fully accountable for their crimes, no matter how horrific (one inmate we met had been convicted of beheading his uncle), and place them in a prison with no facilities for rehabilitation, struck me as horrifically unjust. What’s more, the inmates were so eager to learn, and so excited to be out of their cells and playing childlike games, that I could no longer maintain my belief that some or all of them were anything as reductive as ‘just bad’, even though some of them had been convicted of the most abhorrent crimes imaginable.

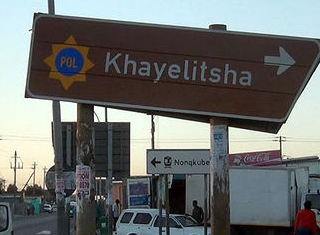

Khayletisha Satellite Office

Khayletisha is the largest township on the Western Cape, so I was eager to visit the Clinic’s satellite office there. It is run by a charismatic man, affectionately named Uncle John, who previously worked as the head of a large financial organisation, and is now semi-retired. The satellite office works with cases at the Khayletisha Magistrates’ Court, which was opened in 2002, to improve ac-cess to justice for those living in the townships. Other townships have since followed suit.

During our time at Khayletisha, we shadowed a prosecutor who works for the Priority Crimes Litigation Unit, mostly on cases falling within the ambit of the Prevention of Organised Crime Act. At the time, the prosecutor was working on an armed robbery case, and we were given the chance to observe examination in chief and re-examination by the defence attorney, as well as cross examination by the prosecution.

The contrast between the advocacy style of the prosecution and the defence was stark, to the extent that the defence attorney had to repeatedly be warned that her re-examination had to be limited to the matters covered in the cross examination. What’s more, the defence attorney was representing all three defendants, and the manner in which she conducted her advocacy with one of them came perilously close to violating some of her core duties, primarily the duty to act in the best interests of her client (that is to say, not to base the defence of one on the prosecution of another!).

The prosecutor we worked with was very keen to discuss his work. Most interesting was that the Prevention of Organised Crime Act was based on a piece of American legislation, and that it had been subject to criticism, on the basis that it allowed the courts to violate people’s constitutional right not to be arbitrarily denied their property. To explain, Section 26 of the Act authorises the courts to issue a restraint order, prohibiting a person who has or will be charged with an offence under the Act from dealing in any manner with any property subject to the restraint order. The courts also have a discretion in terms of Section 26(6) to make provision in the restraint order for the reasonable living and legal expenses of the defendant. Criticism has been directed at the exercise of that discretion, on the grounds that failure to use it violates the right to a fair trial, including the right to legal representation.

It was also interesting to learn that, in certain cases, such as drug trafficking, the Regional Court (one level above the Magistrates’ Court) was able to give a life sentence, but with an automatic right of appeal.

Exploring the Western Cape

This account of my time in South Africa would not be complete without a mention of the fantastic things I got to see and do, in probably the most awe-inspiring place I have ever been, despite having travelled extensively. Cape Town is a fascinating place, in that it straddles the first and third worlds, like no other place I have visited. One minute you can be faced by poverty at its starkest, and the next you can be faced by the most incredible luxury imaginable.

Cape Town, and the Western Cape more broadly, is also naturally magnificent. We were extremely lucky with the weather, and found plenty of time to climb Lion’s Head and Table Mountain, take a long weekend in the Wilderness National Park, and explore both the Indian Ocean side, and the Atlantic side. We were also extremely lucky with the exchange rate, and ate out twenty eight nights out of thirty, for a smidgeon of the price we would have paid back home.

Also worth mentioning is the welcome we received from UWC students and staff. We made good friends with a student called Sam, who had a fascinating story of being raised in the Gugulethu township, and being paid to attend private school by his grandmother’s employers.

One weekend, he took us to explore Gugulethu, and meet the people of his church.

To finish with two slightly less virtuous tales, we made countless visits to free wine tastings, at the many fancy wineries in Stellenbosch. We also spent our last night together having a braai with the student attorneys, and I flew back suffering from perhaps the worst hangover I have ever had.