What follows is a retelling, and deeper examination of a lecture by Professor William Schabas attended by City Law School student (and Lawbore journalist) Ashley Gate.

In the basement auditorium of City Law School, where we lay our scene, the “Decolonising Human Rights Law and International Criminal Law” lecture was held on a snowy Monday evening in December in London. The Lecture was chaired by City University’s own Dr Andrew Wolman, who began the evening by introducing us to the illustrious career of Professor William Schabas.

William A. Schabas is a professor of international law at Middlesex University in London, emeritus professor of international criminal law and human rights at Leiden University, as well as being an emeritus professor of Human Rights at University of Galway, where he founded the Irish Center for Human Rights, serving as its director for many years. Additionally, Professor Schabas is a distinguished visiting faculty at the Paris School of International Affairs, Sciences Po and a door tenant at 9 Bedford Row. He is an Officer of the Order of Canada and a member of the Royal Irish Academy. Professor Schabas has been a prolific writer in International Criminal Law and Human Rights Law for decades. Authoring over 350 articles and twenty books with discussions including, but not limited to: the law on Genocide, the death penalty and the International Criminal Court.

His writings have been enormously influential, being cited regularly by courts and tribunals worldwide. Professor Schabas has also acted as a member of the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission and chaired the U.N. Voluntary Fund for Technical Cooperation in the Field of Human Rights and has acted as a council in cases within the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court and the European Court of Human Rights just to name a few of his practitioner roles.

The research conducted by Professor Schabas was first inspired in the midst of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic lockdown by the Black Lives Matter Movement, a social movement born from the death of George Floyd in police custody. Floyd’s untimely death after being pinned beneath three police officers for almost ten minutes sparked what may be one of largest social movements in United States history. The study was originally planned to be one detailing racial discrimination within international law. Over the course of Schabas’s research, however, an unexpected yet complimentary theme emerged: the role of countries within the southern hemisphere (the ‘global south’) in formulating policies to counteract racial discrimination within international law. More generally, these countries outside of the northern hemisphere’s westernised hegemony were driving forces behind the expansion of International Human Rights Law. They were a powerful force that the academic literature has tended to overlook, neglect and deliberately ignore.

The critical school of international legal scholarship being referred to is the Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), whose scholars are commonly referred to as TWAIL-ers. TWAIL scholars attempt to reexamine international law while being keenly aware of the fact that international legal development in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries was very much related to colonialism and the legal needs of European powers as they attempted to dominate the rest of the world.

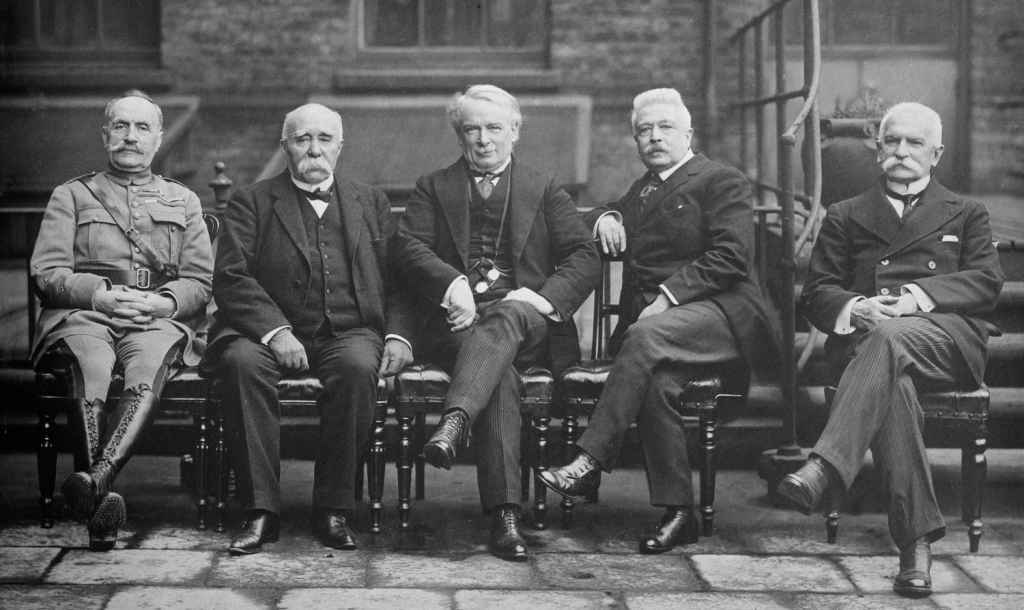

Here is the story for tonight, one that has taken place over the past 100 years. It begins at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, one of the first conferences where countries outside of the European hegemony played a significant role in negotiations. Japan, for example, came with their own list of “wants and needs” alongside all of the other countries, both large and small. But Japan’s hopes for the conference were revolutionary for the time. They came with the intent to entrench the recognition of racial equality into the legal framework of the League of Nations (the United Nations predecessor). Japan’s attempt came in the form of a proposed clause that would be weaved into the Convent of the League of Nations, recognizing what was referred to at the time as “racial equality”. In common legal literature, the attempt is described as a ‘failure’ but this, Professor Schabas argues, does not do justice to what had occurred. You see, Japan was actually quite successful in convincing the States at the Paris Peace Conference to support the clause in its entirety. It was vetoed by only two delegations: the United Kingdom and the United States. When it came to the vote, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson announced that the vote had to be unanimous, and he was not in favour. Notably, at an earlier vote on a different clause proposal that same day, Wilson stated that votes did not need to be unanimous.

The issue of racial inequality arose multiple times within the work of the League of Nations from 1920 until its dissolution at the outbreak of World War II. Two notable cases concerned the Mandate of the League of Nations, which effectively controlled the legal status of territories which were transferred into the control of other countries following the first world war. Notably for our discussion was the redistribution of German colonies around the world. After World War I these colonies were redistributed into the hands of the victorious powers including the United Kingdom, France and Japan.

The region controlled by South Africa in particular became a point of international discourse almost immediately after the mandate went into effect and continued to be so until 1990 when the territory, now known as Namibia, gained independence. While the term ‘apartheid’ had yet to be coined, it was clear early on that South Africa’s regime was a segregated and racist one, much like the other colonial regimes of the age. What differentiated South Africa was its incredibly brutal approach to the League of Nations mandate in Southwest Africa. The first acknowledged genocide of the 20th century occurred in Southwest Africa against the Herero and the Nama people at the hands of the Germans, and South Africans continued a similar trend of brutal oppression of the people of Southwest Africa after the colonies were redistributed.

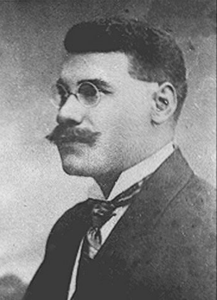

In 1922 a massacre was conducted by the South Africans which unfortunately would have gone unnoticed by the international community if a journalist from one of the western European powers had not witnessed it and relayed the information up north. When the massacre was brought to the League of Nations’ attention, the league’s sole delegate of colour, Louis Dantès Bellegarde of Haiti stood up in front of the League’s General Assembly and condemned the massacre, calling on the assembly to act. This resulted in an intensive inquiry by the League of Nations leading to resolutions being adopted in response. Remember that name, Dantès Bellegarde, as he will reappear later in our tale.

The Covenant of the League of Nations did not mention racial discrimination, and it also lacked any reference to human rights. As such, the work that would later become the foundation of International Human Rights Law was very preliminary and summary in nature. Some of the earliest work appeared in The Permanent Mandates Commission (PMC) as the commission began getting petitions from victims of discrimination in these redistributed mandated territories. The mandate which dealt with these previously German-owned colonies was managed by people who had experience overseeing colonies, in other words, the delegates running the commission were experienced, European colonists. The foundation of International Human Rights law rests on the shoulders of the colonizers themselves, as such the PMC wasn’t a friendly environment for issues dealing with racial discrimination within the colonies. The climate of the commission can be better understood through examples of its activities. One was when Anna Wicksell, the Norwegian delegate to the PMC, after taking an interest in education within the African territories, went to the United States and examined the treatment and education experienced by black Americans in the segregated Jim Crow school of the southern United States. Upon returning from her travels, she wrote a report that was entirely inspired by the segregated education system whose policies would then be implemented into the African territories under the League of Nations mandate; the Jim Crow era system being used as its model.

We move now to the aftermath of the second world war and the subsequent birth of the United Nations. An era of human rights standards setting conducted mainly by European intellectuals, who met and debated what human rights norms would be. Such meetings resulted in the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. During this time period, another delve into human rights was being conducted by countries of the global south, one which has been widely overlooked. Limited in power and number as most southern global territory was still under colonial rule, yet to gain its rightful independence. In 1947, the first official U.N. Commission on Human Rights commenced. At that meeting, however, the U.N. Secretary-General announced that during previous ‘unofficial’ commission meetings hosted in 1946 in both London and New York, three important resolutions had been founded on the topic of human rights. The first resolution was about racial discrimination faced by the Indian diaspora population residing in South Africa. The next was a resolution on prejudice and discrimination in general, and a third resolution was on the topic of genocide. What the Secretary-General did not mention in his speech was that all three of those resolutions came from countries from the southern hemisphere.

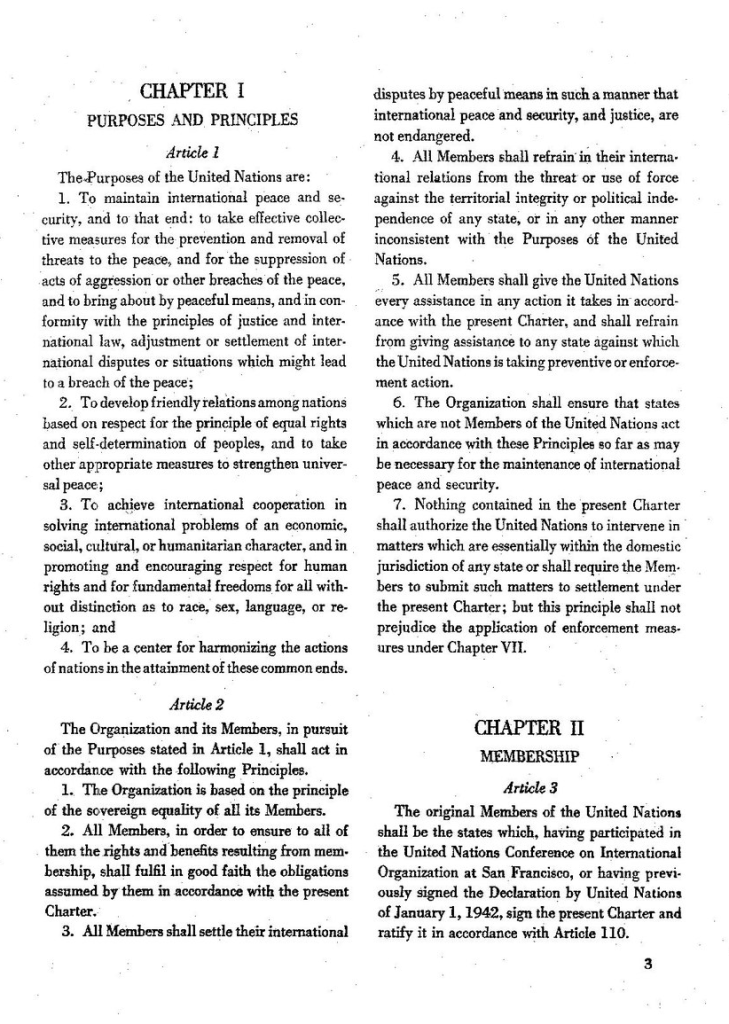

Now, when the Charter of the United Nations was being adopted there was quite a quarrel over whether it would even make references to human rights. The allied powers of France, the United States, the United Kingdom and the USSR had basically abandoned original promises to reference human rights within the charter, with many references being gutted during the 1944 Dumbarton Oaks Conference. At the last moment, the Chinese delegate Wellington Koo, who had been at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and had voted in favour of the Japanese resolution on racial inequality, “flirted” with the idea of pushing the aforementioned clause in 1944. His attempt was chased away and shot down by the other allied powers, namely the United States delegation, but the actions of Koo became well-known in global circles. When references to human rights were finally included in the U.N. Charter, subduing the references was Art 2(7) of the Charter; the domestic jurisdiction clause, “[n]othing contained in the present Charter shall authorise the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state…”

Basically, when the Indians arose in the General Assembly in 1946 calling for a resolution condemning the discrimination against the Indian diaspora in South Africa, the British, Americans, French and others attempted to use Art 2(7) as means to shut the resolution down. India argued that the case was not one of entirely domestic jurisdiction as it concerned a diaspora population. By an extremely close vote, the Indians succeeded in getting the resolution adopted. Shortly after, however, the resolution was not followed up on and became somewhat obsolete.

The Second resolution, which focused on racial discrimination and prejudice in general was proposed by Egypt. Professor Schabas sees this resolution as an attempt to somewhat make up for the lack of a human rights declaration actually within the U.N Charter. Egypt’s initial reasoning for proposing this resolution was due to incidences of anti-semitism in eastern Europe. This resolution was adopted unanimously by the General Assembly. For many years to come the resolution would be referenced commonly by the General Assembly and in later resolutions dealing with racial discrimination until the enactment of the Convention on Elimination of Racial Discrimination in 1963.

To understand the third resolution, we must first be reminded of resolution 95 The Nuremberg Principles, proposed by the United States. The following resolution adopted by the assembly was resolution 96 The Crime of Genocide and was proposed by India, Cuba and Panama. When the Cuban delegate addressed the assembly and proposed resolution 96, he said, “We are here to fix a hole in the Nuremberg judgement.” What was he referring to? Well, both the 1945 Nuremberg Charter of the International Military Tribunal and its judgment in 1946 confirmed Crimes Against Humanity (CAH) as the persecution of minorities or civilian groups within a population, even a State’s own population. During the trial and subsequent judgement, the delegates from the United States, France, Britain and the Soviet Union insisted on limiting the notion of CAH as crimes committed in association with War Crimes and Crimes Against Peace. The issue was that the crimes CAH had to be associated with, according to this judgement, are only enacted with a nexus to war. In other words, CAH would not be able to be alleged during times of peace. This restriction to only wartime applicability is what led India, Cuba, Panama and others to create a second resolution pertaining to genocide, resolution 96. Countries of the south recognized that CAH needed to be recognized in times of war, and in times of peace, consequently expanding the jurisdiction of CAH to the acts of colonial powers within their territories.

Many years later, the minutes of the London Conference where that limitation on CAH was born would be released. We can now read the remarks of the American negotiator and Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Robert Jackson as he explained that they had to limit the scope of CAH because “we have in our own country circumstances where minorities are unfairly treated.” A very polite way of referring to Jim Crow-era policy.

Fast forward to 1952, piggybacking off of the resolution first proposed by India in an attempt to protect persons of the Indian diaspora residing in South Africa, the first ever U.N. commission of inquiry was created by the General Assembly with the purpose of reviewing actions occurring in South Africa. At first, the inquiry was presided over by Ralph Bunche, an African American diplomat and scholar working within the UN at the time. However due to his winning of the 1951 Nobel Peace prize and the newfound commitments related to the honour the U.N. chose a new head. The inquiry into the apartheid was then presided over by our old friend, Dantès Bellegarde.

A change in the tide of the United Nations occurred during the early 1960s thanks to the joining of newly independent African nations. The General Assembly was forever transformed and began to resemble, somewhat, the makeup of our world. The delegates from these new nations were understandably impatient for progress. Their main topic of concern? Racial discrimination. Even so, it takes three or four years for these new nations to be elected into the committee bodies responsible for human rights and protecting against racial discrimination as at the time they were completely full of Western European and Other States (WEOGs) including the United States and Canada. No matter, they went to the General Assembly and called for the creation of a Convention, thus the 1963 Convention on Elimination of Racial Discrimination was born alongside a robust mechanism for enforcement. In a matter of a few years, this convention was created, this is due to the newly independent countries of the south as the WEOGs had been “puttering around” with two other covenants for almost twenty years. A few years later another project is presented to the U.N., with heavy backing from southern countries, the 1973 International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid.

At around the same time, in the 1960s an interesting development in International Criminal Law was afoot. In the majority of legal academia, International Criminal Law development is described as hearty up until 1954 when it “sputters out” the reason behind such a trend is normally described as the Cold War, and the matter is left until the 1990s ‘resurgence’. Professor Schabas admits that he too wrote and even taught such claims of the 45-year “sleeping beauty” that was International Criminal Law, before conducting his latest research. It is a common narrative, but it is not the full truth. While it is true that the General Assembly put the project of an international criminal court on the back burner in 1954 until a definition for the crime of ‘aggression’ could be decided upon. Even when a definition was decided upon twenty years later, the idea of an international criminal court was not revived.

But the part of the story that is not well enough known is that in the early 1960s the African countries started calling for apartheid, racial discrimination and other actions by oppressive colonialist regimes in Rhodesia and the Portuguese colonies to be considered Crimes Against Humanity. The western countries fought back, arguing that CAH was defined in Nuremberg, and such issues would not apply. Luckily, the African countries had sufficient muscle in the U.N. General Assembly to get the terms into resolutions. In 1975 there were three General Assembly resolutions that recognized CAH being committed in southern Africa, an incredibly important, and understated development in International Criminal Law. One conventional example that is discussed in depth in legal academia is the Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity adopted by the General Assembly in 1968. Notably, this convention recognizes CAH in peacetime. But what is less commonly discussed is that the convention was first proposed by countries of the west in 1965 because they were concerned about statutory limitations applying in Germany and other European countries with respect to war criminals from the time of the second world war. African countries argued that the limitation should also apply to crimes including apartheid. Once that occurred, the western countries resisted and stalled the convention. They still do, none of the WEOGs has ratified that convention since 1968. The African countries then drafted, produced and pushed through the General Assembly the Convention on apartheid in 1973, an incredible convention for International Criminal Law during a time in which it is still considered to this day as being in a lull period. Innovation in International Criminal Law did not stop there. The African countries during this time also proposed that CAH should not only be considered to occur during peacetime but also be subject to universal jurisdiction. It should come as a shock to none that western countries were not too fond of such innovations. Belgium, during a 1973 debate on the subject, called such use of universal jurisdiction abhorrent and outrageous. Interestingly enough, Belgium many decades later would later become the “poster boy” for that same type of jurisdiction. They only changed their mind later in the 1990s when they managed to create a form of universal jurisdiction where European courts stand in judgement on the rest of the world.

Another thing the western countries were opposed to whereas the African countries insisted upon was that they revive the project of an international criminal court, such calls for the court’s creation can be found within the apartheid convention of 1973. Finally, at the end of the 1970s, the African countries managed to get a resolution that mandates an expert study to prepare a draft of a convention that would do just that. While the draft created in 1981 does not move forward immediately, it does, however, become the foundation for the statute creating the International Criminal Court which was first drafted during the early 1990s. Professor Schabas concluded by noting that somehow the United States has managed to oppose, boycott, resist and be absent from pretty much every progressive development on racial discrimination in the United Nations since 1946. To quote Professor Schabas, “do I need to say why?” Thankfully, through greater research and a decolonized lens, we begin to move away from the glorification of the colonial powers.

Ashley Gate is a master’s in law student specialising in international Human Rights Law. With a previous background working as a medical aid during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic back in United States, she has a keen eye for the intersectional aspects of health inequity. Ashley has a passion for politics, history, and gardening. Ashley is a member of the 2022-23 Lawbore Journalist Team.