Regulate AI. Add basically any question word to that statement and you’ve landed on a hot topic in information and data protection law. Who should regulate AI? How should we regulate AI? When should we regulate AI? Frankly, can we regulate AI even if we all agree it’s probably the right thing to do?

Wait, what even is AI?

It was these questions that the ILPC (Information Law & Policy Centre) of the IALS (Institute of Advanced Legal Studies) sought to address with their annual conference; this year entitled “Regulating AI in a Changing World: Oversight and Enforcement”, and held on the 20th and 21st November.

For anyone in a rush reading this article in between gulps of coffee I can summarise the overall picture as follows:

AI is really bad stuff and the UK is really bad at dealing with it.

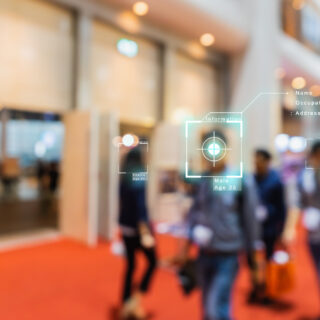

The introductory talk was of interest less specifically to lawyers but was certainly to all of us as citizens. Dr Brian Plastow – the Scottish biometrics commissioner – explained some of the ways in which AI is impacting on police operations. We are all familiar with the idea of fingerprints and DNA evidence (and Dr Plastow emphasises that the overwhelming majority of crimes are still solved this way) but recent years have seen the police experiment with a far more controversial tool: live facial recognition, or LFR. This uses cameras to scan faces appearing in public while an AI-powered system compares the facial vectors to a police watchlist. If it flags a match, it will alert the police who can then approach the individual.

Many are concerned, however, about the implications on privacy and the prospect of a mass-surveillance state turbocharged by AI. Dr Plastow is of the opinion that there is a place for LFR in modern policing but it is limited. For example, if there was a specific threat to an event it would be proportionate to deploy LFR in the surrounding area. He thinks, however, that the police are bad at communicating with the public and opaque use of LFR at events like the Notting Hill Carnival unnecessarily undermine public trust. If the police were to adopt a policy-first (rather than tech-first) approach and were more open about their intentions with emerging technologies, the result might be better.

Straight after the talk came the panel, which was, for me, the highlight of the evening and very relevant to a law student interested in the landscape of information and tech regulation. Call me simple-minded but it was enjoyable basically because of a straightforward (verbal) bust up between the first and second speakers about the effectiveness of the ICO (the Information Commissioner’s Office).

First up Mairead O’Reilly, Legal Director of Enforcement at the ICO, gave a short presentation on the work the ICO has been doing to ensure good practice in companies’ use of AI. She highlighted the variety of ways in which they exercise a positive influence. For her, it’s not just issuing monetary penalties but publishing their “biometrics and AI Strategy” in June (in which the three buzzwords are transparency, fairness and accountability), promoting the idea of a statutory code of practice and working with organisations to ensure more careful consideration of AI-related risks. For example, the ICO successfully flagged concerns with Snapchat’s “MyAI” rollout after which the company made some changes to their approach.

Then, the second speaker gave an excoriating review of the ICO’s record. Cambridge’s Professor David Erdos noted that GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) had promised us genuinely dissuasive action from regulators but all the ICO can present are two fines against Clearview AI (£7m) and TikTok (£12.7m). When TikTok has an annual turnover of $17.2bn, that negligible sum is just going to be considered the cost of doing business, rather than anything like a dissuasive action. The EU, he argued, has done vastly more in a similar timeframe per the Land Hessen and SCHUFA judgment from the CJEU. It’s particularly embarrassing that the TikTok fine alone represents 95% of the value of the ICO’s monetary penalties in that year. For Professor Erdos the ICO makesis, frankly, a pathetic attempt at regulation at precisely the time we need these bodies to be stepping up to the challenge.

The other panellists weren’t so involved in this argument but they had interesting perspectives nonetheless. Nuala Polo represented the Ada Lovelace Institute which has researched what the public thinks about all this. Their survey suggests a high level (72%) of general support for regulation, particularly for people from ethnic minority backgrounds. She rightly notes that there are concerns around LFR (live-facial recognition) unjustly discriminating based on race – particularly if the models are trained on mostly-white faces. Gus Husein represented Privacy International and lambasted the UK as uniquely stagnant in policy development around AI regulation. He blames the “we can neither confirm nor deny” attitude of the UK government on any question about data usage as having made proper scrutiny totally impossible.

The event was extremely well-organised by the ILPC and – as you’d expect from any event at the IALS – gave the audience a great deal to think about. It posed more questions than answers, however, and I would say an audience member came away with a more sophisticated understanding of the challenges of AI than how to meet them, but every talk and panel was worthwhile nonetheless.

If I had one suggestion it would be to introduce some more balance to the debate. However cynical lawyers and academics might be about AI there’s no question that it is big business – especially in the US. Sitting in the council chamber of the IALS, I was struck that I was listening to people fervently argue in favour of restraining AI on the same day that Nvidia apparently dismissed fears of an economic bubble by beating expectations of its forecast revenues to reach $57bn. It is an economic reality that unprecedented multi trillion-dollar market caps are being driven by huge investments in AI and it’s possible that by regulating it heavily in the UK, we will only encourage that growth to manifest elsewhere. I certainly think it’s an argument that deserves a fair hearing and having a more “pro” AI panellist at the conference would have enriched the debate.

Richard is a graduate of Durham University and aspiring barrister having won Durham’s major mooting and mock trial competitions. Before writing for Lawbore he was Head of News for his student broadcaster, PalTV, a researcher for The Times newspaper and an aide to a Member of Parliament. He is developing an interest in commercial and public law, particularly where it intersects with information, media and technology. He currently on the GDL at City.