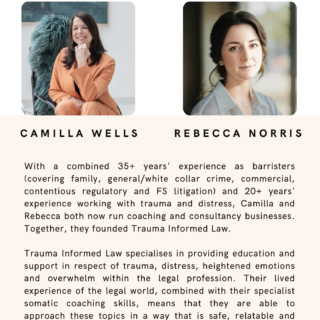

With a combined 35+ years’ experience as barristers (covering family, general/white collar crime, commercial, contentious regulatory and FS litigation) and 20+ years’ experience working with trauma and distress, Camilla and Rebecca both now run coaching and consultancy businesses. Together, they founded Trauma Informed Law. Trauma Informed Law specialises in providing education and support in respect of trauma, distress, heightened emotions and overwhelm within the legal profession. Their lived experience of the legal world, combined with their specialist somatic coaching skills, means that they are able to approach these topics in a way that is safe, relatable and empowering, allowing space for discussion and response.

We were very lucky at the City Law School, to have a tailored session delivered by Camilla and Rebecca to our academic staff and students on 27th November. This formed part of our regular ‘Wellness Wednesday’ series. Prior to the event, Malak Noori, one of the team of Lawbore journalists, had the opportunity to interview them about their work. It’s a detailed piece with lots of questions, so massive thanks to them for dedicating the time to speak with us.

Can you share a bit about your background in law, specifically your early career in family and criminal law? What drew you to these areas initially? [to Camilla]

Camilla’s energetic and enthusiastic personality drew her to family and criminal law because she wanted a challenging, non-office-based job. Being in court every day, cross-examining, making submissions, and relating to the human side of cases was enjoyable for her, and was a good fit with her sympathetic nature. She became pretty resilient with time and recognised the need for quick thinking and flexibility in these fields. She also appreciated the dynamic and friendly nature of her job and her position within the legal system. She left the Bar after 23 years in practice and found her time at the Bar to be memorable and rewarding.

Can you tell us about your previous legal practice, particularly your journey as a barrister and mediator? [to Rebecca]

In her professional career, Rebecca has practiced both criminal and commercial law. She started off working on general crime and in prisons, including abroad, at the criminal bar. She later moved into the business world, where she observed a human element present in all of these situations. The emotional nature of legal proceedings was brought to light by the trauma, stress, fatigue, and personal difficulties that clients in both regions experienced. She became more interested in mediation since it gave her the opportunity to focus on peacefully resolving disputes rather than the combative nature of the legal system. Understanding the common human experiences that underlie both criminal and commercial law, she has spent the last ten years working mainly in the commercial sector.

Was there a pivotal moment or a specific experience that pushed you toward trauma-informed coaching, was there a specific case that took such a heavy toll on you, making you realise you needed extra support to deal with the impact of that, or was it just an accumulation of many difficult situations?

Rebecca shares that her journey was sparked by her interest in the tension between human imperfection and the pursuit of a perfect justice system. In practice, she experienced moments that impacted her deeply. When cross-examining a witness who was accused of lying, she saw the emotional toll on them. She believed that people could be re-traumatised due to the adversarial nature of the legal system. It felt like this showed a lack of concern for their welfare, and others within the system.

She began to see other examples of recurrent trauma; high-level executives she encountered in the business sector, often found the legal process intimidating and overwhelming, and they lacked a coping mechanism.Rebecca observed how solicitors were not adequately trained to handle human reactions and the emotional challenges that come up in the legal profession. She altered her career to focus on training and education on trauma reactions in the court system after being inspired by these experiences and realising the impact of trauma.

Camilla spoke here of the challenges that emerged as a result of some aspects of the legal career that she loved. The expectation to be dynamic, as well as ensuring high level client care and focusing on being empathic, caused her to nearly burn out and challenged her work/life balance. She struggled with setting boundaries and keeping a balance when it came to the emotional weight of her work, compounded by long hours. She later nearly reached a breaking point, and she chose to make changes to her way of working, including reducing the volume of cases she took on.

The empathy that she had with her clients who faced systemic issues, such as legal aid cuts and delays in family law, on top of their legal issues, made her feel a weight of responsibility for things that were beyond her control. She noticed that there were insufficient resources to address these issues. She also wondered why there was no focus on the family lawyer’s own mental health, whilst they themselves put a huge emphasis on their clients’. Consulting experts like Dr. Anthony Feinstein, she began researching the impact. With his help, she learned about the effects of stress and distress on the mind and body, and as a consequence decided to change the focus of her profession. Her emphasis shifted to prioritising justice and humanity, working towards changes in the legal system. Together with Rebecca, she is currently working to create a more encouraging and equal environment for solicitors and their clients.

As a somatic coach, what inspired you to integrate body-oriented methods into your trauma-informed approach? [to Rebecca]

Somatic practices reconnect people with their bodies to better handle stress and trauma. Rebecca’s work integrates neuroscience and emphasises the body-mind connection to create healthier responses to challenges in life and work. Her shift towards somatic practices happened when she realised how lawyers neglect the role of the body in managing emotions, often focusing solely on their logical minds. She noticed this connection through multiple scenarios — during a project using rugby to help young men in prison process emotions through physical activity, and through an observation of her traumatised rescue dog, which highlighted how animals instinctively release stress by shaking it all off, unlike humans who often let it build up.

Could you explain how somatic coaching techniques work in practice? How do they help legal professionals or clients dealing with trauma and stress? [to Rebecca]

They focus on the body instead of relying solely on a cognitive approach. People can identify their behavioural patterns, understand their origins, and even pinpoint what needs to change. Yet, their logical awareness isn’t enough to override automatic responses, and so therefore this causes them to fall into the same patterns. Somatic techniques, on the other hand, release deeply held patterns and trauma stored in the body through different methods such as movement and stillness. This approach helps to interrupt automatic reactions and instead creates healthier patterns of response.

What are the main issues your clients face? Are there particular stressors that seem to impact legal professionals today? [to Rebecca]

The main issues that legal professionals face today are their exposure to trauma and distress, long working hours and overwhelming demands which keep them from meeting basic needs like rest or eating. Many lawyers also have a strong tendency towards perfectionism and this can make them feel disconnected from their emotional and physical well-being.

Additionally, systemic issues like court delays and inadequate facilities create further stress, particularly when lawyers must handle sensitive client interactions in less-than-ideal conditions. This all results in burnout and emotional pressure.

I know there is a huge stigma revolving around well-being and taking care of oneself. Have you encountered resistance when introducing these practices? [to Rebecca]

Rebecca answers this question by referencing her own initial resistance to well-being practices. She acknowledges that she also, just like many in the legal sector, was pushing her physical needs aside. Rebecca explains that resistance to these practices is common because individuals aren’t in a safe place to engage with them, and notes how it is valid and recognised in their training as a protective mechanism. However, many legal professionals begin to realise the importance of well-being practices over time, and they often seek out one-on-one sessions. So, there is definitely still resistance but also a growing understanding of trauma’s impact within the legal profession, which leads to a softening of attitudes towards well-being practices.

As your work involved training and coaching to organisations, could you share an example (anonymously) of an organisation or a client that transformed significantly after implementing your training? What were some of the most noticeable changes? [to Camilla]

Camilla shares the example of a production company and a network in the TV industry, to whom she was giving some trauma-informed training related to true crime and blue lights programming. After giving the training, in both clients there was an increase in awareness and discussions about the effects of such work, since both clients recognised the importance of addressing the impact of traumatic content on their teams. This led to broader training across multiple teams, including entire companies, and also a culture of support where employees could support one another, especially through reflective groups where people would share their experiences. Camilla emphasises her pride in reducing the suffering that had previously been hidden or endured in silence.

Same with your work, as you provide support and education to managing stress and burnout in the corporate workspace, have you personally seen any improvements in people who incorporated these? [to Rebecca]

Rebecca has seen improvements from incorporating stress and burnout training. One key result is that by validating the experiences of stress, overwhelm, and burnout, individuals realise it’s a natural response, which encourages self-care. This is especially important for lawyers working in high-pressure environments, such as corporate investigations, where they need to manage their own stress to effectively support their clients and witnesses.

In her work, Rebecca has observed that when lawyers are trained to recognise their own burnout and also understand their clients’ stress, it helps them provide better support, leading to improved outcomes. For example, when witnesses are overwhelmed, understanding their stress allows for better quality evidence and more positive experiences. Without this training, witnesses can feel too pressured and may even abandon the case, negatively affecting both the case and their well-being. Overall, the training has a positive impact on team cohesion, client care, and the integrity of the justice system.

Your work with victims of domestic abuse and prisoners must be very different, or is there actually a lot of crossover? [to Rebecca]

Rebecca tells us that there is a lot of crossover between her work with victims of domestic abuse and prisoners. She points out that, after all everyone is human and has experiences that shape their paths, which can be similar. This realisation of a common struggle comes after people feel safe enough to remove the masks that they wear to hide their humanity. She puts this into perspective by describing a project where prisoners, trained in rugby, played against a team of lawyers. The players connected as humans, despite their differences.

We know that there is a definite link between wellbeing and sustainability in careers; do you have any examples you can share from your own professional journey or from others that illustrates this? [to both]

Camilla shared that self-care is a skill that needs to be practiced and prioritized, and that the more it’s practiced, the better one gets at it. She discussed how, since leaving the bar and building her own business, she’s encountered stressful moments, vulnerability, and self-doubt. Despite this, she has always made self-care a priority, learning from her near-burnout experiences during her time as a barrister. Camilla explained that self-care for her can involve “micro-moments” where she takes small, effective steps to recharge, as well as longer activities, like going for a run, that may require more time. She emphasised the importance of finding self-care practices that individuals truly enjoy and resonate with, and that it’s important to make them personal and sustainable for long-term well-being.

Rebecca shared an example of a client who was overwhelmed and burnt out from work, ultimately needing long-term sick leave. Through their work together, Rebecca helped the client understand the underlying causes of their burnout, bringing compassion and developing strategies for self-care and resilience. This client has since returned to work, feeling better equipped to handle the demands of a high-stress role. Rebecca emphasised that understanding one’s well-being, distress, and trauma is essential for sustaining a career, particularly in demanding professions. She highlighted that people are not machines and sometimes need time off to recharge. By acknowledging personal needs and allowing space for self-care, individuals can better balance their humanity with their work, ultimately leading to more sustainable careers.

The Times highlighted the Legal Cheek survey recently (13 Nov – I’m 26 and earn £140k. My ‘perks’? Burnout and bullying bosses) do you think it is vital to highlight these findings, or is it more important to change the narrative away from the 70hr weeks and demanding clients to something else? Is it realistic to imagine a more equitable environment in firms? [to both]

Camilla responded by highlighting the importance of understanding the “real story” in the legal profession. She noted that while surveys may reveal bleak realities about the pressures and challenges lawyers face, there is often reluctance to openly discuss these issues. Camilla highlighted the need for a trauma-informed legal system that takes into account human systems, including the brain and nervous system. She likened the subconscious to an “embodied Google Drive” that stores significant life events, which then influence a person’s well-being. Camilla stressed the need to examine what’s stored in this system and implement protective mechanisms to ensure a healthier and more sustainable environment.

Rebecca stressed the significance of articles such as this, as they highlight the real struggles and voices of people in the legal profession, including issues like burnout, bullying, and overwhelm. She stressed that while acknowledging these challenges is crucial, it’s equally important to bring forward solutions. This is where trauma-informed law comes in—recognising the distress and trauma while offering compassionate and practical solutions. She mentioned the need to shift the legal culture and treat lawyers as human beings, advocating for both raising awareness and providing concrete steps for improvement. Rebecca also pointed out that while media outlets sometimes focus on sensational headlines, it’s important to include a counterbalance that addresses how to address these issues.

As a final question, do you have any advice for students or young professionals on how they can protect their well-being as they enter the legal field? What steps can they take now to build resilience and manage the emotional and pressurised demands of the profession? [to Rebecca]

Rebecca offered some key advice for students and young professionals entering the legal field on how to protect their well-being and build resilience, this can be broken down into 4 categories:

- Science: Educate yourself about stress and how your body responds to distress. Understanding the science behind your reactions can help you validate your experiences and realize that these responses are natural human reactions.

- Strategy: Have a plan in place for when you’re feeling off or uncomfortable. Think about what actions you can take to regain your balance, such as seeking support or practicing self-care.

- Curiosity: Approach situations with curiosity. If something doesn’t feel right, trust your instincts,and ask questions. Understanding the source of your discomfort can help you address it.

- Compassion: Show yourself compassion, especially when you’re trying to prove yourself in a new career. It’s okay if things don’t always feel perfect. Prioritise your well-being and be kind to yourself as you navigate the demands of the profession.

Once again, a huge thank you to Camilla and Rebecca for not only delivering a session to us here at the City Law School, but also for agreeing to this interview. Want to find out more? You can view a recording of Camilla and Rebecca’s recent session. Thanks also to Malak Noori for penning the questions and writing it up for Lawbore.

Malak is a second-year Law Student at The City Law School, an aspiring barrister, and a dedicated student representative for her cohort. She enjoys connecting with others, and learning from their diverse experiences, finding joy in sharing knowledge and fostering a supportive community. Malak is eager to use her voice to provide valuable insights and resources to help fellow law students navigate their journeys.