Back in November, Chris King, a member of our Lawbore journalist team carried out a fascinating (and as it turned out – oft-interrupted!) interview, which appears below as a must-read for all those interested in EU law.

Lawbore would like to thank Professor Panos Koutrakos for arranging this interview with Sir Jonathan Faull, who had a distinguished career at the European Commission and is chair of European public affairs at the Brunswick Group. He led the EU’s pre-referendum taskforce and has worked in areas including competition, justice and home affairs, market regulation and financial services. In essence, what Sir Jonathan does not know about the EU is not worth knowing, and we were very grateful to him for sparing the time to speak to us in the plush surroundings of the ground floor of the City Law School…

CK: You were head of the taskforce just before the referendum. Have the things you feared might happen actually happened, as in, did you expect it to be as bumpy as it’s been?

JF: First of all, frankly, until I don’t know how many days or weeks before, we didn’t expect the result to be to leave. The opinion polls were unclear, close, and got closer as the vote drew nearer, but I think the night before, it was not a foregone conclusion that the vote would be to leave. So yes, we were surprised and shocked and all the rest of it… what I do think is, and remain to this day shocked by, is that those who wanted Brexit didn’t prepare for it. I remember a discussion in early 2016 with the Leave campaign people and I said ‘What are you going to do about Northern Ireland. Where’s the blueprint? What’s going to happen?’ And they said:

‘That’s a matter for the government, not for us. We’re the leave campaign, we’re not the government, there’ll be a government and the government will have to deal with it. And secondly, technology will sort things out. You don’t have to stop every lorry at the border any more, there are pre-customs clearance arrangements, trusted traders and all that.’

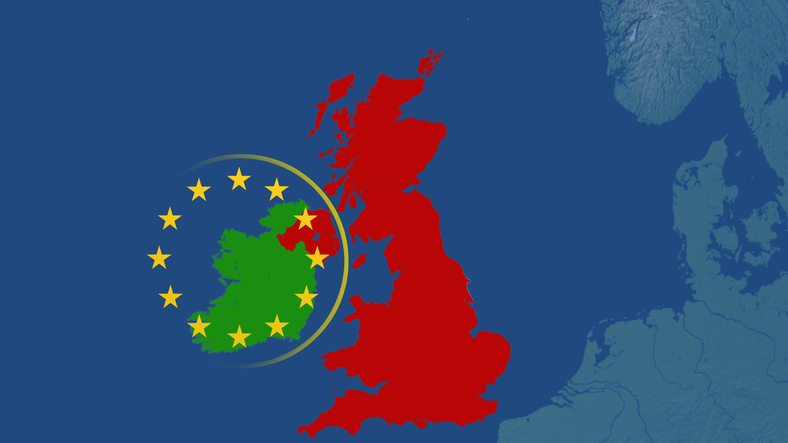

And I said, yes, all that is true, but I said two things: one, there will have to be checks, there is no border in the world between two separate customs territories, properly managed, where you don’t stop at least a considerable proportion of people and vehicles crossing the border, and everybody has said there should not be physical infrastructure on the Irish land border. And secondly, I said, but I was wrong, I was foolish… [I said] you’re going to be found out in the campaign. You will have to explain what’s going to happen. It’s crucial. That’s where the EU and the UK meet. And they got away with it … We had ‘Brexit means Brexit’, we had ‘Red, White and Blue Brexit’ and now we’ve got [Sir Keir Starmer’s slogan of] ‘Make Brexit Work’. I mean, fine, but what does it mean in practice? Now governments have to make those decisions, they find it very difficult. Northern Ireland politics are complicated, the EU is difficult to deal with and the UK has been through all the convulsions of the past three years, but we’ve got to sort it out. Ireland’s not going away, it’s like Russia. There’s going to be Russia after the war… there’s going to be Ireland in the EU, for the foreseeable future, of course.

CK: I found it interesting that you were saying you were optimistic about the way things were going to go, but obviously Northern Ireland is a really difficult point…

JF: It is very difficult…

CK: Has it to got to the stage now where people were so exhausted from the Brexit campaign, it was like a long war. Are people so exhausted from it that they might rather just–

At this point, a few minutes in, our interview turned into a panel discussion…

GDL student: May I join your meeting?

JF: As far as I’m concerned… it’s an interview…

CK: Yes, that’s fine…

We get back to the questions, at least for a bit…

JF: Yes, people are exhausted and want to move on. And God knows there are other things happening in the world which require our attention, I mean, we’ve all been through a lockdown, a pandemic and there’s a war not many hundreds of miles away from here. And there’s climate, and all the other things going on in the world, economic dislocation… So, yes, a lot of people think ‘time to move on’. The British are not Martians, they are not very different from other Europeans, we should be able to sort this out. Why are we still arguing about this?

CK: Well, that’s a question to put to the people, I suppose…

JF: But we are…

CK: The other thing, just on what you were saying about the war in Ukraine and in terms of what the panel in general was saying about the potential for the EU to be flexible, do you think the fact that there’s war in Ukraine and it’s really forced the issue, and it’s forced all these countries to work together and put things into perspective that actually, Brexit is quite trivial compared to a war in Europe, do you think it’s going to make it easier for the EU to make those concessions that might otherwise be very uncomfortable?

JF: Yes, I do. I do think that. And I think it also highlights what the UK is quite good at. The UK is a member of the [UN] Security Council, it does have a tradition in foreign, security and defence policy, it’s a nuclear power, with France, the other European member of the Security Council. There are nuances between the British and other European positions, but they are nuances. I mean, Russia is a partly European country, we have borders with it not very far away. Yes, it shows that squabbles about EU membership and how to manage Brexit are of less significance than hundreds of thousands of people dying in a pandemic, and a war on European territory not very far from here. That’s true. So that should cause Europeans to think about what unites them rather than what divides them. Now every country has its different history, geography and economic circumstances, but basically the European issues … they’re all the same. Demography, ageing populations, the challenge of climate, most of them post-colonial realities, certainly France, Belgium, the Netherlands, the UK. The UK is different because the experience of the Second World War was very different. For most European countries, joining the EU meant we are democratic, the soldiers stay in the barracks, we are not a dictatorship any more and we respect human rights. The British don’t associate Europe with that at all.

CK: It was a source of legitimacy for Europe wasn’t it?

JF: Of course. But for the British, the soldiers do stay in the barracks. They never came out of them. We didn’t have a coup d’état. We weren’t occupied and we didn’t occupy. So the experience of 1939-1945 was completely different. That explains a lot of the, I think, vastly exaggerated differences between the UK and continental Europe, and the Irish experience is different again. But Ireland, like the Baltic States and some others, shares the post-colonial [reality]… we were occupied. For Ireland, being in the EU means we are a sovereign state, respected all over the world. The British don’t think like that. Back in 1973, we joined the EU at a rather low ebb in our politics and economics, because we were exhausted and where else could we go? … We’ve got to trade with our neighbours. Now my hope is, and I hope it’s no longer just for that, but if everybody says the deep-seated problems of the British economy are low growth, low productivity, plus shared with the rest of Europe … the rise of China, tech industries are in the US, not here, all this stuff (picks up LB’s rather battered iPhone) is designed in California and made in China, we share all those problems.

CK: So a common solution is sensible…

JF: Yes, and we should work together. We don’t have to agree on everything, we don’t have to love each other. There’s a lot of romance about Europe, sort of messianic, because don’t forget, the two main political forces which made the European Union are Christian democracy and social democracy, and they’re both messianic. There’s an idea that somehow all of history culminates in … second coming … or communist revolution and everything’s going to be fine. So there is a tendency among professional Europeans in Brussels to think that it’s obvious that all European history was culminating in this great moment of unity. Who knows what’s going to happen in 50-100 years’ time. And the UK was never comfortable with all of that. First of all, we’re not very ideological. The English in particular don’t think constitutionally, at all… the Scots do, and the Welsh do a bit, and the Irish do, because they are the minority nations. England… people say to me, where’s the English parliament, where’s the English government? Well there isn’t one.

At this point, our interview goes a little off-piste. Sir Jonathan asks one of the students who has joined us for the interview/panel session where he is from and is taken aback to find out that you can simultaneously be Russian and Dutch yet not like football. But back to the interview, ever so briefly…

JF: But the English are weird. Where’s the constitution, where’s the government and where’s the parliament? My continental friends say to me all the time. ‘Is there a parliament in London?’ Yeah, the British one…

At this point, a student from India asks about the nostalgia for empire in this country, which Sir Jonathan is only too happy to discuss, pointing to the array of symbols that hold pride of place in the British psyche. We get on to the point of living in the past, which naturally leads to Russia, whereupon Sir Jonathan is confronted with the possibility that Russia might break up. He seems rather surprised. Our GDL student goes on. Russia will lose the war. Wow, says Sir Jonathan. He clearly wasn’t prepared for such a hot take. Other students join us, perhaps they can see how stimulating our chat is. We go on to discuss what might happen in Russia. The assumption in the West is that Russia will still be there within the current borders after the war, says Sir Jonathan. ‘Vladivostok is not going to be Japanese.’ Quite. ‘Moscow is not going to be Polish.’ But our Russo-Dutch interlocutor says similar things were said about the likelihood of war breaking out in the first place. The discussion continues. After some time, bravely, our reporter seizes his chance and attempts to re-establish an interview…

CK: May I just pull this back really quickly? Because obviously people coming on to this course might think, why are we still bothering to study EU law, it’s not relevant any more… If you’re somebody coming on to this course, say next year, and maybe you’re somebody who has certain feelings about Brexit, what’s the best way for them to direct their energies?

JF: Well, first of all, and for lawyers, it’s a fascinating legal construction. It came out of nowhere, it’s not a state, it creates institutions–

We are very briefly interrupted by a former colleague of Sir Jonathan’s at this point. It’s like Piccadilly Circus in here…

JF: As a legal system, it’s very interesting. It’s supranational, somehow sovereign governments obey the law most of the time. There’s no prison. You don’t put the King of Sweden in prison. But it works. Shared sovereignty, so for those who know a little bit of international law, it’s a new chapter in international law, which may be of interest to other regions of the world. For Brexit, locally for this country, it’s interesting, of course. It’s already dropping off the agenda in continental countries because they have other problems, but it’s also an interesting phenomenon. You join an international organisation, you leave it, what happens, how do you deal with it peacefully? Nobody’s fighting. Even in Ireland, the peace has held. This is all being done in a civilised way.

CK: One last one, do you think the British experience is enough to put anyone else off trying it?

JF: So far, yes. Now, you asked what we thought in 2015-16, we were very nervous about contagion. So people said the Danes, the Dutch, other countries with populist governments, strong anti-European feelings…

CK: Greece as well, there were fears about…

JF: Greece, indeed. [It was feared that] if the UK leaves, they will follow. There was a sort of conspiracy theory as well… the UK will go around, talk to the Dutch, the Danes, because they did this in the 1950s. The British said we’re not going to join–

Another attendee wants to say goodbye to Sir Jonathan. At this point, we’re feeling a bit bad for taking up his time, but he makes for a great subject… As he says, ‘I’ve been hijacked’

JF: The British reaction to the Common Market in the 1950s was to create EFTA (the European Free Trade Association), a much looser free-trade area, but gradually, all of those countries except Switzerland and Norway… and Liechtenstein and Iceland I suppose… joined the EU. So, yes, one theory in 2015-16 was [that] the UK would leave and create a magnet effect on other countries, and the EU will break up. Now, because of the chaos of Brexit here, because of the pandemic, because of the war, so far, you have the contrary. Sweden and Finland are joining Nato. Denmark is getting rid of its reservations about [the] European foreign and security policy. Nobody is leaving. The new post-fascist Italian government … Euro, Nato, no problem… whereas their predecessors wanted to leave. So for the time being, but nothing is forever, for the time being, EU solidarity has worked. It worked in the pandemic, it’s worked for Ukraine, but… the winter is coming, next winter will be tough. [Vladimir] Putin hasn’t disappeared, he can divide us. Everybody is going to China separately. [German Chancellor Olaf] Scholz went to China, [French President Emmanuel] Macron’s going to China, [Giorgia] Meloni, the Italian prime minister… [Rishi] Sunak will go to China. And these are smart people. They will try to divide us. So nothing is permanent. But so far, the EU has held together.

At this point, our auxiliary interviewer steps in to ask what Sir Jonathan would do with Viktor Orbán? Cue a collective ‘hmm’…

JF: What would I do? I’d [something along the lines of tell him off]. So far, they live with him.

And Poland, asks another member of our cadre of journalists…

JF: Of course, Poland has now (this phrase comes from our auxiliary interviewer, not Sir Jonathan initially) whitewashed itself because of Ukraine. Not pro-Russian. So people have forgotten about the bad things in Poland.

At this point, the lights go off in parts of the City Law School. Time to wrap things up, not least because Sir Jonathan’s friend keeps popping over to check on him and remind him that, while he kindly entertains an enthusiastic bunch of GDL students, he has a dinner appointment…

JF: But Orbán, you sort of hope that it won’t last forever and the Hungarians will see sense, and meanwhile, you live with it. It’s a pity for gay people, human rights activists, and democrats, but as long as it doesn’t spread to other countries, we’ll put up with Hungary. I suppose it’s cowardly, but what else can you do? Throw them out? What’s the point?

Chris King is a GDL student at the City Law School and future trainee solicitor. Former national newspaper journalist. Interested in environmental, media and public law.