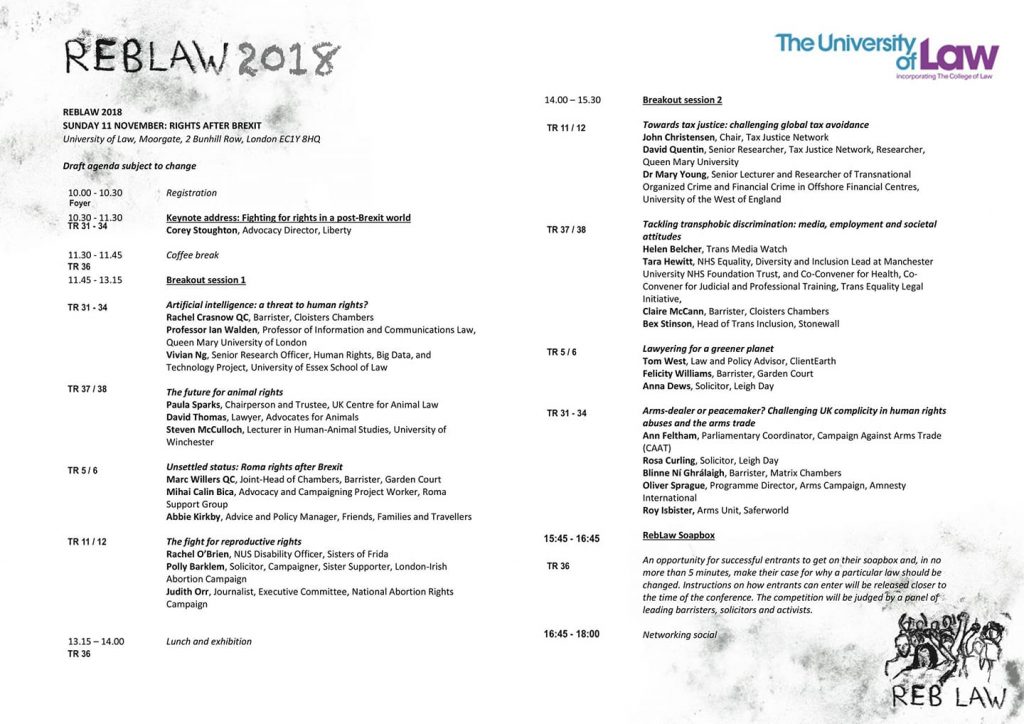

When I heard that the 3rd annual Reblaw (short for ‘Rebellious Lawyering’) conference was happening at the University of Law’s Moorgate campus on Saturday and Sunday, 10th and 11th November, I took note. There are very few legal events exploring the juncture between social justice/ environmental campaigns and how lawyers can engage with them, so I jumped at the chance of purchasing one of the Sunday tickets for a tenner.

When I heard that the 3rd annual Reblaw (short for ‘Rebellious Lawyering’) conference was happening at the University of Law’s Moorgate campus on Saturday and Sunday, 10th and 11th November, I took note. There are very few legal events exploring the juncture between social justice/ environmental campaigns and how lawyers can engage with them, so I jumped at the chance of purchasing one of the Sunday tickets for a tenner.

Arriving at the Moorgate campus at 10am on Sunday morning, the delegates were guided through the maze of corridors by the helpful Reblaw volunteers, mostly University of Law students. Speaking to a fellow delegate while waiting for the key note address, they told me that Saturday had been been an exhilarating experience, so I anticipated something special for the day.

The day was to consist of a keynote address, two optional talks and the Soapbox competition. The following is a summary of the content of each of those events.

Keynote Address

The Keynote speech, entitled ‘Fight for Rights in a Post-Brexit World’, was delivered by Corey Stoughton from Liberty, a civil rights campaign group. Her main contentions were that although Liberty had been neutral on Brexit, they were concerned about the ‘hidden minefield’ that lay ahead, such as the loss of important EU laws underpinning human rights and the constitutional shift of power from the Parliament to the Executive.

The Brexit deal is currently in a state of purgatory – ‘what’s the deal with the Deal?’. The government plans to take a ‘snapshot’ of EU law currently used in a domestic context and incorporate it into UK domestic law, for continuity – the ‘cut and paste’ procedure; over time unwanted laws would slowly be repealed. The one exception to this is the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, which would not to be carried over into UK law.

The first problem is that equality rights in the UK are very fragile. The Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA) does not apply to private individuals or companies. Previously, domestic law could be disapplied if there was a conflict with EU law. Ms Stoughton gave some examples of the kinds of UK legal claims pursued using EU general principles, like pension rights for gay couples and workers’ rights in diplomatic buildings. Under Brexit, fundamental human rights protections are in danger of being singled out for the cut, but not the paste.

The second problem is the use of ‘Henry VIII powers’ and the right of ministers to amend primary legislation with secondary legislation (ie statutory instrument (SI)). Under UK constitutional law, Parliament makes changes to the substantive law, while SIs should only be used for technical changes. However, there are no limits written into the Henry VIII powers.

This would be a surrender of Parliamentary power. Secondary legislation has little or no Parliamentary oversight, or even when using an affirmative procedure, statutory instruments are seldom challenged. There will be no accountability, and power will shift from an ‘open’ Parliamentary process to a ‘closed’ Ministerial one. The cumulative transfer of powers to the executive branch is part of a larger trend going on constitutionally, which will be amplified by Brexit. There must be more meaningful scrutiny.

Ms Stoughton then went on to explore ‘rebellious lawyering’, a concept developed by Gerald Lopez, an American lawyer, and whose ideas inspired the Reblaw conferences. Lopez stated that the law was not inherently just and legal teaching did not include an education on how to use the law to seek justice. This search for justice included four important principles: 1) changing narratives, 2) getting proximate (ie getting closer to those on the margins of society), 3) staying positive and 4) doing uncomfortable things (ie requiring courage, challenging the statement ‘this is not how things are done’). Ms Stoughton claimed the English Bar vitiated this search for justice, with principles like the cab-rank rule and its elitism. She claimed the US had a much stronger tradition of ‘movement lawyering’, assisted by a community of support coming out of, for example, the Reblaw conferences there.

In closing, Ms Stoughton spoke about her fears for civil rights if UK legislation, like the Equalities Act and HRA, did not become constitutional Acts. She encouraged lawyers to use the EU legislation now, while it was still valid, in order to entrench it in UK law.

Thus began the first of the optional break-out sessions. I attended….

Unsettled Status – Roma rights after Brexit

The Roma originated from North-west India and arrived in the UK in the 1500’s. At one point, ‘living like a gyspy’ was a capital offence in England, and this law was only revoked in 1750. Today there are between 100,000 and 300,000 Roma in Britain, and they are one of the most disadvantaged populations.

The talk was opened by Marc Willers QC of Garden Court Chambers, a seasoned barrister representing Gypsies, Travellers and Roma. His cases generally involved poor defendants in criminal cases brought by the State. In the 1980’s legal aid meant it was possible to do this sort of work, but since the legal aid cuts, it has become almost impossible to earn a living at the criminal bar. Many areas of law have been decimated by the cuts, like housing and welfare benefits. This has seen many people leave the profession, but to Marc, this was an area of law which he was passionate about. When he was not getting ‘proximate’ with his clients in their caravans, Marc acts as a trustee of a Gypsy/Traveller/Roma campaign group focused on changing policy.

During the Nazi holocaust hundreds of thousands of Roma were interned in the German concentration camps, in what the Roma termed ‘the Devouring’. How did the Nazis get away with it? By using propaganda to denigrate the Roma. ‘Hate speech’ against nomadic groups is still common today. Marc cited comments made by a recent Irish presidential candidate about Irish travellers. At a festival in Sussex, the crowd burnt an effigy of a gypsy caravan. There was no prosecution of the matter. Hate speech on newspaper websites is not being moderated. Newspapers often indulged in irresponsible reporting. However the police are not interested in tackling it. Even procedurally, hate speech prosecutions must go to the Attorney General first. The focus of ‘hate speech’ prosecutions have been around anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, with none against anti-gypsy or –Roma speech. There is a general unwillingness and few cases are brought.

Marc told a story where, following a Conference on Travellers, involving the police, social workers, lawyers and travellers, the delegates went to a JD Weatherspoons pub, only to be told that they could not come in since they had ‘been at the travellers conference.’ Some of the delegates took the matter to trial and won.

Marc told a story where, following a Conference on Travellers, involving the police, social workers, lawyers and travellers, the delegates went to a JD Weatherspoons pub, only to be told that they could not come in since they had ‘been at the travellers conference.’ Some of the delegates took the matter to trial and won.

Next Mihai Calin, a project worker for the Roma Support Group, spoke. He is social worker from a Roma family, and was brought up in Romania. He claimed that he had experienced discrimination in both his personal and professional life. He now works for the Roma Support Group, a charity which has been going for 20 years. They provide direct support (eg advice on benefits, jobs, etc) and indirect support (eg policy and campaigning) for Roma in the UK.

Many Roma came to the UK to escape the negative experiences in their own countries, and prefer the UK for the opportunities it offers (eg schools for their children). However, stereotypes still exist. Brexit has caused a lot of anxiety; many fear that if they leave the UK to see family or to work, they will not be allowed back in when they return. There was an increase in hate crime following the Brexit vote, especially against vulnerable groups like the Roma. Brexit has created a ‘hostile environment’, with, for example, landlords required to check if tenants are eligible to reside in the UK. The same is being proposed for employers.

In order to apply for ‘settled status’, people need to fill in an 85-page form, and generally require the assistance of expensive legal professionals; one person paid £3,000 for a lawyer to help put in an application for them. Many Roma need interpreters and face-to-face help.

Abbie Kirkby, a worker with Friends, Families and Travellers (FFT), spoke last. The work of FFT was focused on ending discrimination against gypsies, travellers and Roma, and working to protect the nomadic lifestyle. The charity was formed following the forced and violent evictions after the passing of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994. FFT does capacity building work with smaller groups, case work and campaigning. FFT is also involved in the All Party Parliamentary Group on travellers, influencing policy at a national level.

The process for groups like the Roma to get ‘settled status’ is a very high-tech process, not suitable for vulnerable groups. The post-Brexit applications for settled status is still in the testing stage, and there are already barriers for groups like the Roma, namely digital exclusion, language barriers, evidential issues and ‘suitability criteria’ (such as previous criminal records). To prove ‘settled status’, they are expected to have evidence of living in the UK for over 5 years, which included documents like tenancy agreements, mortgages, accounts, proof of working, etc. Many of the new and older traveller populations just don’t have this kind of documentation. Culturally, traveller populations bring their extended families wherever they go, especially their older relatives. Thus wives and older people will be at most risk, since they do not have the documentation to prove ‘settled status’. Even if a Roma is granted ‘settled status’, he or she will not be given any card or documentation saying he or she has any such right; this will exist in ‘the cloud’ somewhere. The Roma are being used as a test group for the new immigration procedures post Brexit, so the UK government needs to get it right for the Roma otherwise other groups will face similar problems.

Roma need support in their communities and not from an Assessment Centre. The decision about whether any applicant could stay was at the discretion of Home Office officials. The government has allocated £9 million to ‘outreach’ work for the process, which is in danger of being snapped up by large corporations winning this contract. Fortunately, the Law Centres Network is considering putting in a bid.

For those interested in the legal side can subscribe to FFT’s regular bulletins which covers legal issues relating to travellers, such as wide injunctions and ‘no-go zones’; similarly the Travellers Times is a useful resource and the updated 3rd edition of the ‘Gypsy and Traveller Law’ by the Legal Action Group will be out in early 2019.

That led me on to the second option break-out session, following a lunch of sandwiches and samosas, which was…..

Towards Tax Justice: challenging global tax avoidance

This session took the form of a panel discussion between three Tax Justice Network members, John Christensen (economist), David Quentin (PhD student and ex-lawyer) and Dr Mary Young (financial crime lecturer and researcher).

Mr Christensen started off with looking at tax’s role in monetary theory – States issue money and withdraw this money from the economy using tax. Tax is part of a property regime. Historically, the failure of the tax regime came about post-WWII with the rise of the multinational corporation (MNC). Britain for a long time blocked any moves to tax British capital in its [former] colonies. Any frameworks for taxing MNCs (eg unitary taxation) have been blocked by the Britain and the US, another form of ‘imperialism’.

Tax avoidance is a moral issue, while tax evasion is a legal issue – although the difference is one of semantics. Lawyers are enablers, they provide the glue which holds it all together. ‘Creative accountancy’ involve accountants creating structured transactions rooted in the law. Tax avoidance is a transactional operation. It focuses on ‘commercial awareness’, gaming the system and framing everything in terms of risk. Tax avoidance is a ‘risk play’. It implements a transaction which may achieve a tax saving, but not necessarily.

Proponents of tax avoidance claim that ‘tax is theft’ and that financial crime is victimless. The counterargument is that tax avoidance is theft from the state and therefore should be a crime. Writers in the 1960’s challenged the concept of financial crime being benign with ideas like ‘enterprise theory’ (MNCs work like criminal organisations) and ‘white collar crime’ (professional enablers of crime).

A dominant finance industry creates a ‘finance curse’, much like a discovery of a natural resource like oil creates a ‘resource curse’. The overbearing nature of either industry is bad for the rest of the economy. The economy becomes dependant, captive to it, and the place becomes too expensive to live in. Even IMF studies have shown that a financial industry is good to a certain scale, creating wealth, but when it becomes too dominant, it becomes a source of wealth extraction. Tax avoidance boosts short term share option gains but undermines productivity in the long run.

The finance industry keeps developing countries poor. Global finance enables capital flight from developing countries, and the tax breaks given to MNCs and others serve ‘no useful purpose in developing anything’. MNCs can switch to another country if there is any threat to their profits. This is a form of ‘coercive diplomacy’. The OECD is one culprit, since it sets the tax rules for the rest of the world.

One of the reasons suggested for Brexit was the proposed EU Money Laundering 4th Directive, which required transparency in the financial industry. Particularly worrying to the tax evasion industry was the inclusion of trusts in the Directive, creating a threat to one of the building blocks of offshore secrecy. The UK government wishes to make London the ‘Singapore on the Thames’, open to oligarch capital inflows.

One action Tax Justice Network undertook was to draft an opinion stating that under the law, there was no fiduciary duty on boards of directors to avoid tax, a challenge to the oft stated ‘commercial’ position. This helped change the narrative in commercial practice.

Soapbox Competition

The last event of the day was the Soapbox competition, which involved eight attendees each giving a 5 minute talk on an area of law they would like to change and why. The speakers were to be judged by the audience on ‘persuasion’ and a panel of three barristers/lawyers made the final decision. I had sent in a submission and, to my surprise, was selected. Speakers dealt with topics such as:

The last event of the day was the Soapbox competition, which involved eight attendees each giving a 5 minute talk on an area of law they would like to change and why. The speakers were to be judged by the audience on ‘persuasion’ and a panel of three barristers/lawyers made the final decision. I had sent in a submission and, to my surprise, was selected. Speakers dealt with topics such as:

- ‘why character evidence should not be admitted at trial’

- ‘why vulnerable defendants should have the same rights as vulnerable witnesses’

- ‘introducing no-harassment zones around abortion clinics’,

- ‘why asylum seekers should be able to work after 6 months rather than 12 months’

- ‘data protection rights’

- ‘squatters rights’

- ‘why greenbelt land should not necessarily be protected from development’

Everyone spoke very well and the standard was high in all the presentations. Each speaker dealt with their topic differently, exhibiting different styles of presentation and argument. At the end of each speech, the audience voted by mobile phone on how persuaded they were by the speaker, results ranging from 50% to 95%+. When my turn came to speak, I walked up to the podium, and looked out at the 100+ people in the room. It was scary, but as with all advocacy, you are on the spot and you just have to do it as best you can.

At the end of the competition, the judges announced the results – they chose joint-winners, Myrto, an LLM student and Jake, a GDL student from City! Myrto spoke eloquently, clearly and passionately on her subject of ‘no-harassment zones’, while Jake made an unorthodox (but obviously effective) use of gesturing hands and an accessible dialogue-like style to make his point on ‘asylum seeker work rights’. Congratulations to both who deservedly won the prize of a bottle of prosecco. The judges giving feedback afterwards suggested ‘showing passion for the subject matter’ and that old chestnut ‘tell them what you are going to tell them, tell them, then tell them what you just told them’.

Apparently, there were only 12 people who entered the competition, and seven were chosen. So the lesson for next year’s Reblaw conference is: put in a submission for the Soapbox competition. I recommend it to learn (the hard way) some skills in public speaking in a supportive environment, as well as air an issue you feel passionately about.

The conference ended with drinks in the foyer, a small contingent staying on, while most went their ways it being Sunday evening and all. After a couple of Peronis, I grabbed a last bottle for the road and slipped into the night. The event had been a good one, the early days of a potentially potent force and forum for lawyers, passionate about issues, to share information and ideas. Well done to the organisers, speakers and volunteers for the Reblaw Conference 2018. We look forward to next year’s offering.

Many thanks to James MacDonald, BPTC student at the City Law School for giving real insight into the event for those of us unlucky enough to have missed it!