Criminal trials often adapt well to the silver screen. They unfold as dramatic narratives filled with incisive cross-examination, revelatory evidence, and stern judicial interventions. Yet few trials are more compelling, nor as historically significant than the Nuremberg Trials which began eighty years ago in Germany, only months after the end of the Second World War. In an unprecedented attempt to hold individuals responsible for war crimes, the remaining Nazi high command was brought to Nuremberg to stand trial.

Nuremberg was selected partly for practical reasons. It still had a functioning courthouse, the Palace of Justice, which had survived Allied bombing largely intact. Nuremberg was also potently symbolic to the Nazi regime: it was the site of the Nazi Party rallies, infamously depicted in Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935). It was the place where Hermann Goering – Reichsmarshall and now principal defendant – pronounced the Nuremberg Race Laws in 1935, stripping Jewish Germans of rights and laying the legal foundations for the Holocaust. A decade later, the same courtroom became the stage for the first prosecution of individuals charged with crimes against humanity, establishing the framework for modern international criminal law.

Film-makers have long been drawn to the Nuremberg Trials. Stanley Kramer’s Oscar-winning Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) was the first film to approach the subject. In 2000, TNT aired a docudrama Nuremberg, with Alec Baldwin as chief U.S. prosecutor Robert H. Jackson, and Brian Cox as Goering. In 2025, writer-director James Vanderbilt, best known for scripting David Fincher’s Zodiac (2008), revisits the trials.

Vanderbilt’s screenplay begins with doubts from the prosecutors about whether such a trial would be legitimate. “There is no case law, no precedent for this,” Michael Shannon’s Robert H. Jackson declares. Goering, played by a portly Russell Crowe, sneers: “It is my intention to make this trial a mockery. I feel that a foreign country has no right to try the government of a sovereign state.”

It was the great achievement of the actual prosecutors at Nuremberg that they wereable to establish a precedent for an international tribunal where none existed. Even among the Allied high command, support for a trial was not universal: both Stalin and Churchill initially favoured summary executions of high-ranking Nazis. Yet a decision was made at the London Agreement in August 1945 to establish the International Military Tribunal, with judges representing the four Allied nations – the United States, Britain, France, and the USSR. The tribunal’s prosecutors and judges bore a huge responsibility to act fairly, as many Germans perceived the trials as nothing more than “victor’s justice”.

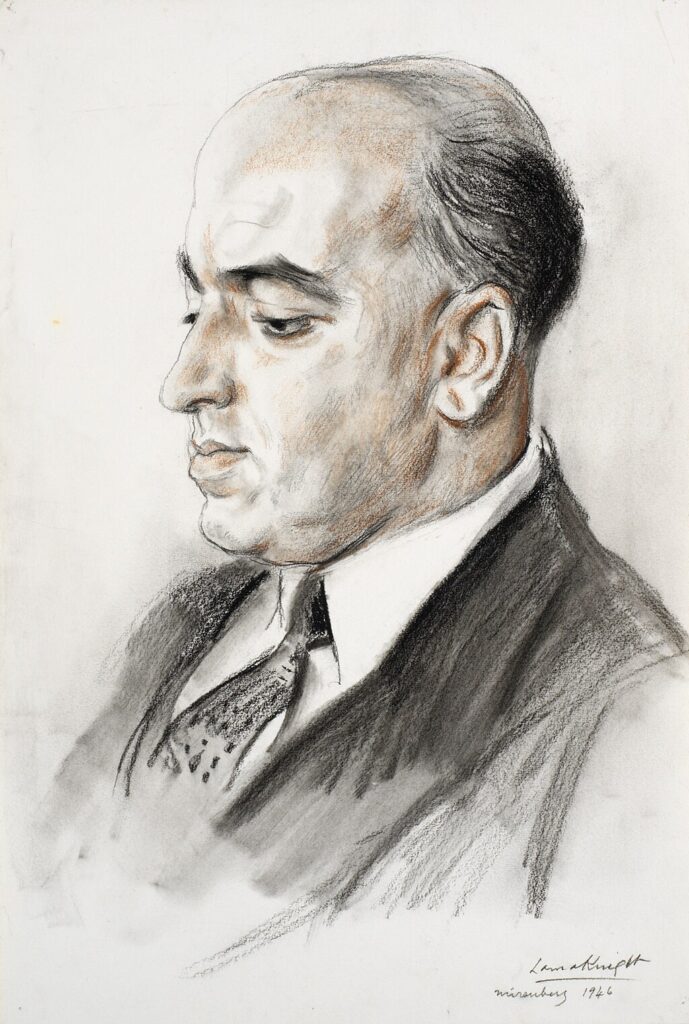

One figure absent from Vanderbilt’s film is Sir Norman Birkett, Britain’s deputy judge at Nuremberg. Birkett wrote a diary throughout, explaining the importance of procedural fairness to the legitimacy of the tribunal:

“To make the trial secure against all criticism it must be shown to be fair, convincing and built on evidence that cannot be shaken as the years go past. That is why the trial is taking so much time and why documents are being piled on documents.”

Source: Norman Birkett, ‘The Greatest Trial in History’ in James Owen, Nuremberg: Evil on Trial (2007)

The tribunal lived up to this principle. All 22 defendants were represented by German counsel, evidence was disclosed between the prosecution and defence, and far from being a mere kangaroo court, its verdicts were not pre-ordained. Three defendants were acquitted, while high-ranking figures like Admiral Karl Doenitz and Albert Speer, Minister for Armaments, received prison terms rather than executions.

The film’s courtroom scenes rely almost verbatim on transcripts from the trial. Jackson’s cross-examination of Goering is portrayed as a failure, faithful to the assessments of many contemporaries and historians. Birkett himself privately criticised Jackson’s approach: “If he is unsure of his case or his facts…the richest opportunity of the cross-examiner is lost. This is the main weakness of Jackson.”

The emotional climax of both the historical trial and Vanderbilt’s film is the screening of Exhibit 230: a documentary compiling footage from the recently liberated concentration camps. The U.S. prosecution turned down offers, including by then-General Eisenhower, to stand in the witness box, in favour of showing a documentary depicting visual evidence of the crimes of the Holocaust. The effect was devastating. Goering – in a characteristic display of hubris – is reported to have muttered “It was all going so well and then they showed that awful film.”

Nuremberg builds to a final confrontation between Goering and Jackson on the stand. It is here that the theatre of the courtroom turns into pantomime. Vanderbilt’s script has Dr Douglas Kelley, played by Rami Malek, save Jackson’s faltering cross-examination by providing private psychological records of Goering to the prosecution. It makes for good cinema, but elevates Kelley far beyond his historical role.

In reality, the trial’s progress was slower, more procedural, and more forensic. The defendants were ultimately indicted on the basis of evidence the regime had meticulously recorded itself. Sir David Maxwell Fyfe KC – played here by Richard E. Grant – is often remembered as the most effective cross-examiner at Nuremberg, but even he did not rely on theatrical flourishes and dramatic admissions. His success lay in presenting documentary evidence contrary to Goering’s testimony, even on seemingly minor matters, such the ‘Aktion Kugel’ policy dealing with Allied prisoners of war, which bore Goering’s signature.

Sir Norman Birkett understood how difficult it was to capture the magnitude of the Nuremberg Trials as they unfolded:

“If it were possible to capture the moment…a contribution to History would be made of the highest value. But there are few Gibbons in this world, and they are not usually to be found among His Majesty’s Judges!”

Birkett’s reference to Edward Gibbon, author of the six-volume Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is apt. Vanderbilt’s film, although compelling, is occasionally reductive. Even with a two-hour-and-twenty-minute runtime, the trial scenes feel too compressed, and essential figures like Maxwell Fyfe only feature as side-characters. Capturing the full historical depth of the trials remains a task fit for a Gibbon, but Vanderbilt’s film, despite its limitations, makes an earnest and worthwhile attempt.

Thanks to Joey Ricciardiello for this terrific review of the Nuremberg film.

Joey is currently studying the Graduate Diploma in Law and is a member of the Lawbore Journalist Team 2025-26. He is an aspiring barrister interested in the criminal and public Bar. Previously, he worked in the House of Commons as a researcher/speechwriter for an MP. He graduated from New College, Oxford with BA (Hons) in History, followed by an MSt in 18thCentury British and European History.